Even a ‘miracle’ needs a safety net: Texas leads in growth, lags elsewhere

The Texas economy has experienced exemplary growth for decades, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as the “Texas Miracle.” The state has led the U.S. in job growth, GDP growth and population growth. Labor force growth has outpaced the nation, driven by domestic and international in-migration. Household income in Texas has risen consistently, growing faster than inflation. Today, by measures such as median household income and unemployment, Texas is on par with the nation.

In other areas, however, Texas lags its U.S. counterparts.

For example, Texas is highest among all states in its percentage of residents who lack health insurance, at more than double the national average. The share of Texas families living in poverty exceeds the national average. Texas public education funding is increasing on a per-student basis although it still trails the nation, and the gap is widening. And Texas is among the bottom 10 states in financial literacy with a sizeable percentage of unbanked residents.

These measures point to challenging economic conditions, affecting a sizable part of the state’s population.

Finally, Texas’ growth itself has given rise to other, new challenges for state and local leaders beyond the obvious need for increased infrastructure and educational funding.

Housing affordability is one such challenge for Texas in the postpandemic world, particularly in metropolitan areas. Decreased housing affordability diminishes one of Texas’ traditional advantages in attracting new workers to the state and can cause economic disruption in vulnerable communities through the process of gentrification.

Taken together, these measures of the highs and lows of the Texas economy give rise to interesting questions for policymakers. Has educational and safety-net public funding in Texas kept up with the state’s economic growth? Does economic growth diminish the need for this type of funding? Or does it increase the need for safety-net funding and other policy initiatives arising from the disruptions growth itself causes?

Texas leads in job growth; household income climbing

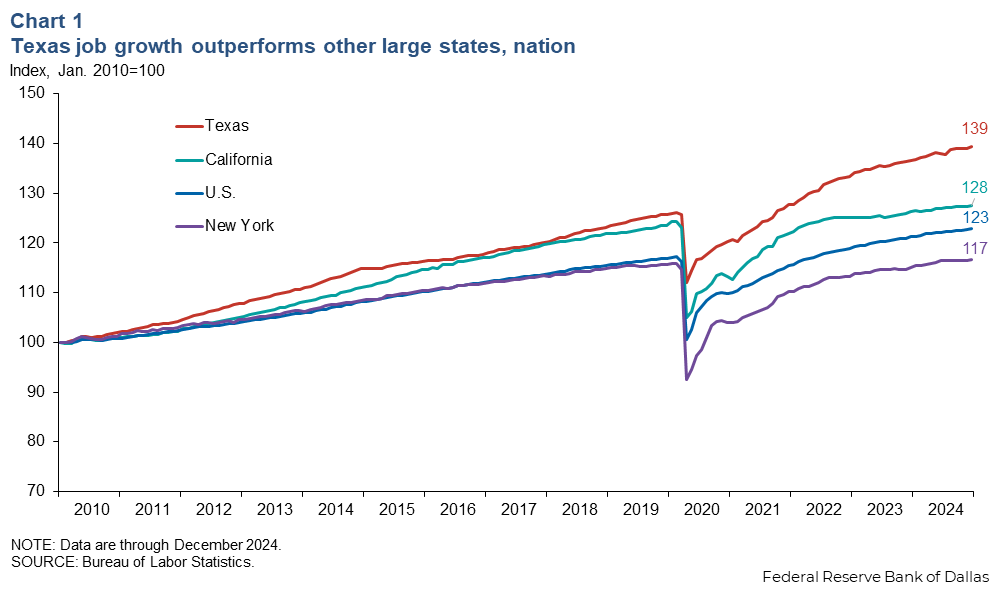

Texas’ population has expanded 24 percent since 2010, with 27 percent growth in the labor force. Employment has expanded even faster than the population or labor force, increasing 39 percent in the state since 2010 (Chart 1). Growth in Texas employment has outpaced the nation, where it rose 23 percent in the same period.

Texas creates more jobs than any other state, fueled by domestic and international in-migration. The pandemic boosted migration to the state, creating a supply of available labor that helped Texas lead the nation in the postpandemic economic recovery. The share of immigrants to Texas with college and graduate degrees exceeds that of the overall Texas population. Immigrants can be employed in sectors in which native Texas workers are relatively scarce.

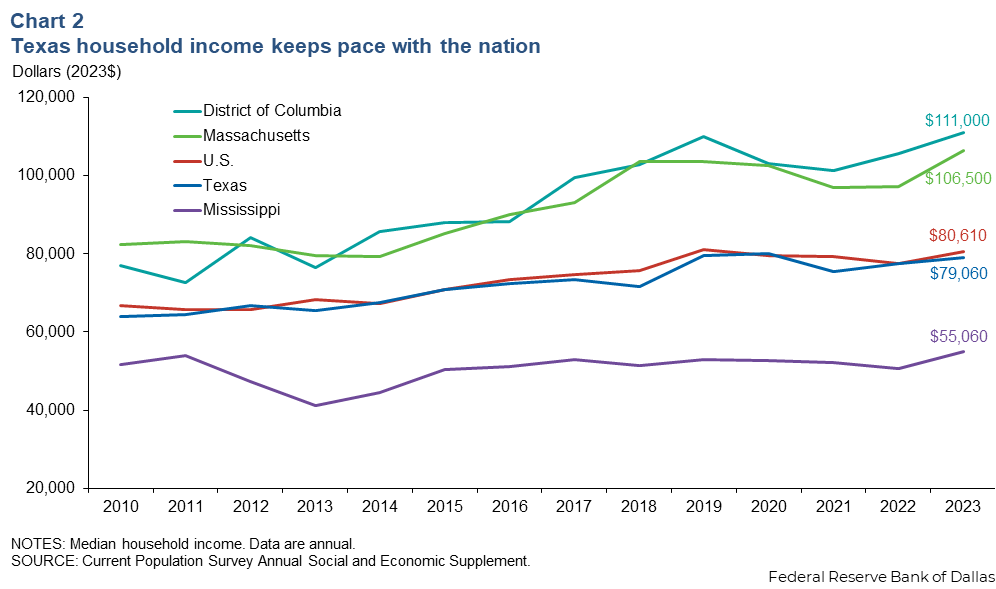

Real median household income in Texas has grown consistently over time and remains on par with the nation, although it’s lower than richer states, such as Massachusetts (Chart 2).

As household income grows, families can afford more goods and services, and the resulting increase in spending boosts the economy. A median household income that exceeds the pace of inflation indicates a rising standard of living. Differences across states in the level of income mostly reflect educational attainment.

Texas lags in health insurance, poverty, financial literacy

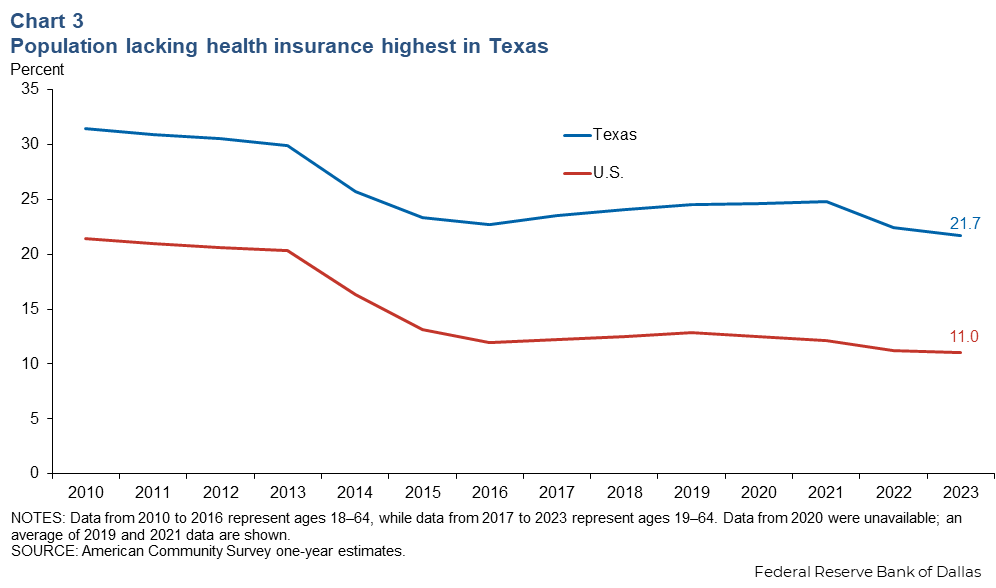

The share of uninsured Texans has declined since 2010 but remains far above the share nationally. In 2023, 21.7 percent of prime-age (18 to 64 years old) Texans were uninsured, nearly double the national share of 11 percent (Chart 3). Notably, this trend extends to the entire population. While 16.4 percent of Texans are uninsured, the national rate is 11.1 percent. By either metric, Texas is the state with the highest rate of uninsured people by a significant margin.

Employers typically provide health insurance for prime-age individuals, yet many uninsured Texans are employed but either unable or unwilling to pay for health insurance. In the U.S., the percent of individuals employed but uninsured is 9.8 percent; in Texas, it is 19.2 percent.

Texas’ high rate of uninsured people can be attributed to several factors. Texas has a large Hispanic population. Hispanics are less likely than non-Hispanic whites to have health insurance. That’s often because Hispanic people earn lower incomes than white people, work for small employers that may not offer insurance or are self-employed. In addition, about 28.3 percent of Texas Hispanics are foreign born. Some may lack legal status and, therefore, are unable to access health insurance. Texas also did not expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. Forty-one states have done so, raising their coverage rates, which pushed Texas lower in the state rankings of share of uninsured people.

Additionally, health insurance is closely tied to poverty. People living below the poverty line are more likely to be uninsured than those above. This is especially true in Texas, where 27.5 percent of individuals below the poverty line were uninsured in 2023, more than double the 13.5 percent of individuals nationally.

Poverty in Texas remains slightly higher than the national average. In 2023, 12.3 percent of Texans were below the poverty line, exceeding the nation’s rate of 11.1 percent, according to the Census Bureau’s Official Poverty Measure. The three-year average, covering 2021 through 2023, was 11.4 percent in the U.S. and 13.1 percent in Texas.

There is an additional measure of poverty, the Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure. It, like the Official Poverty Measure, considers the cost of basic needs as well as a family’s income. However, unlike the Official Poverty Measure, the Supplemental Poverty Measure also factors in government transfers such as SNAP benefits (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistant Program, formerly known as food stamps), medical and childcare expenses, geographical cost of living differences and type of housing.

With these extra considerations, a more well-rounded measure of poverty emerges. Texas does better in its three-year Supplemental Poverty Measure average at 12.6 percent, still higher than the national average of 11 percent.

Financial literacy is another area in which Texas trails the nation. Texas has an unbanked rate of 5.6 percent of households, putting it in the top 10 highest-rate states, according to the 2021 Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households. The U.S. has an unbanked rate of 4.5 percent. In this survey, “unbanked” means no one in the household held a checking or savings account. In Texas, this rate was down from 7.7 percent in 2019 and 9.5 percent in 2017. Financial literacy is crucial to saving, accessing credit and building wealth.

An emerging challenge: Housing affordability

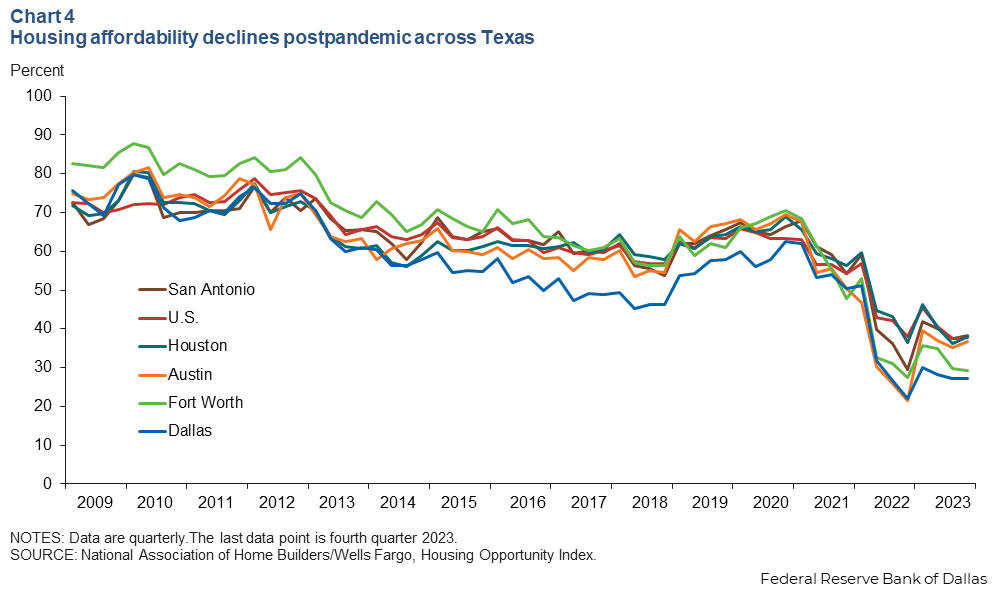

In the postpandemic period, Texas faces a new challenge: housing affordability. Prepandemic, most Texas metro areas boasted average housing affordability of 60 percent, the share of homes sold that a median-income household could afford at the current 30-year fixed mortgage rate (Chart 4). In fourth quarter 2023, the rate had declined to an average of 32 percent in Austin, El Paso, Houston, McAllen, San Antonio, Dallas and Fort Worth.

This deterioration of housing affordability is due to higher house prices as well as the rise in mortgage interest rates since the first quarter of 2022.

Homebuilding was suppressed after the housing crash and financial crisis, creating relatively low supply from 2010-19. During the pandemic, interest rates dropped, leading to record low mortgages that, accompanied by federal stimulus payments and an introduction to remote work, generated high housing demand. The imbalance between supply and demand resulted in record high house prices. Even as the Texas housing supply expands at a faster pace, affordability may remain low as property taxes and insurance costs climb.

Housing affordability has been a longtime advantage for Texas in attracting domestic and international in-migration. Because people tend to move from more expensive to less expensive areas , the erosion in Texas’ cost-of-living advantage diminishes incentives to move here and could lead to potential declines in the state’s rate of population growth.

Data forms basis for policy considerations

While experiencing exceptional economic growth over the past decade, data show that Texas is last or lagging the nation in several key areas. Very high uninsured rates, above-average poverty and low financial literacy, in addition to record low housing affordability point to areas of underperformance in an otherwise robust economy.

The data suggest Texas’ recent economic growth has not diminished the need for policy and public spending to address these challenges and growth may, in fact, have increased the need in some areas.

Recognizing areas in which the Texas economy is both excelling and lagging can lead policymakers to lay the groundwork for an even more vigorous state economy that allows more residents to thrive. Further insights based on data and projections, along with flexible policy approaches, can help Texas improve its standing in areas it underperforms.

About the authors