Shoring up water supply, curbing demand key to Texas’ future growth

Water is essential to the expanding Texas economy and its ability to continue outpacing U.S. growth. However, Texas’ increasing demand for water is running up against its current supply, which is already stressed by extreme heat and more frequent droughts.

Funding for water infrastructure improvements has emerged as a priority for the Legislature during its 2025 legislative session. Absent changes to policy, Texans could face significant water shortages during droughts and constraints on future growth and economic development.

Gauging potential water shortages

The Texas Water Development Board produces the State Water Plan, a blueprint that addresses supply and demand for water during droughts. In 2022, the agency estimated that if a severe drought (“drought of record”) were to occur in 2030, the state would be short 4.7 million acre-feet—more than 20 percent of projected demand.

One acre-foot of water is enough to supply two to three homes for a year. It is a unit of measure equivalent to the amount needed to cover an acre with a foot of water.

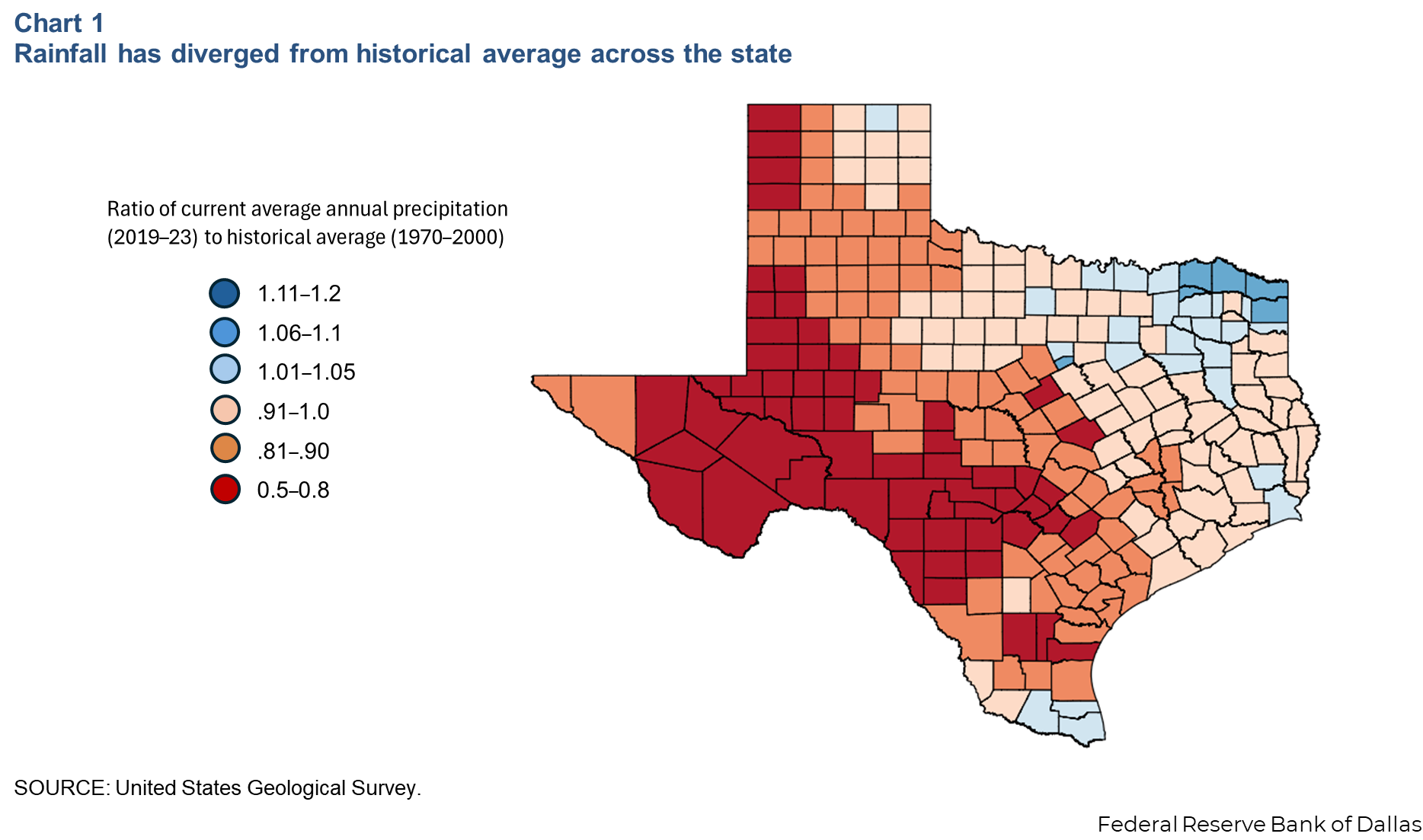

Water resources and potential shortages are highly regional because of Texas’ size. In recent years, portions of East Texas experienced near- or above-normal rainfall, while the western half of the state was drier than normal (Chart 1).

Some Texas communities already face extremely low water supplies. Reservoirs in the Rio Grande Valley are below 25 percent capacity. As a result, Brownsville has limited car washing and landscape irrigation and drained city swimming pools to reduce water demand. The city of Mission has weighed a moratorium on new construction, and Corpus Christi has restricted residential yard watering to conserve water. Areas in central Texas, including Austin, have implemented similar measures as Lakes Buchanan and Travis hover around half capacity.

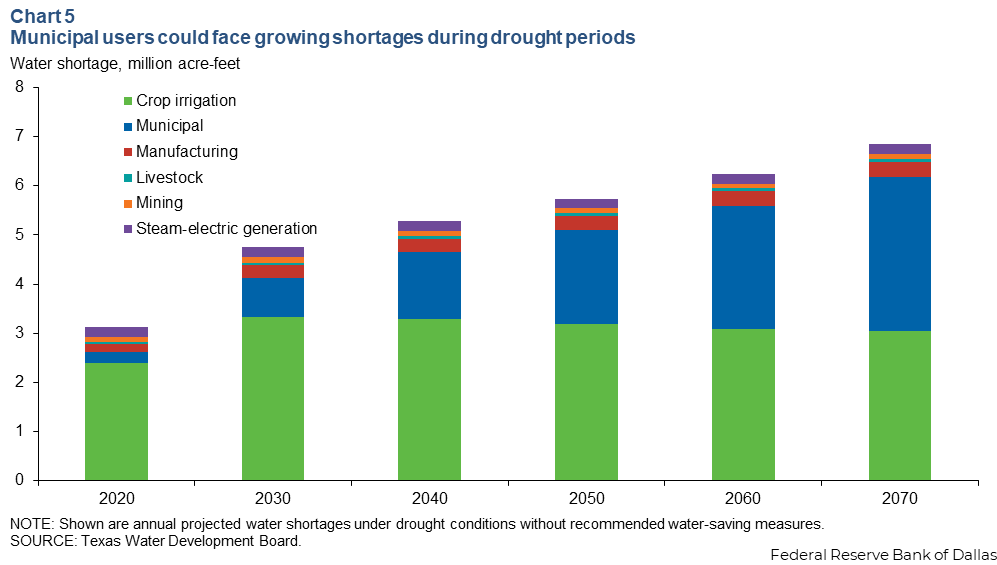

Rapid urban growth and depletion of the Ogallala Aquifer, a prominent water source for agriculture in the Panhandle and West Texas, will exacerbate the impact of future droughts. Under severe drought conditions, the shortage could total 6.9 million acre-feet per year in 2070 if the State Water Plan’s recommendations are not implemented.

Rules differ for groundwater, surface water sources

Texas agricultural users draw mainly from groundwater supplies, while municipal and industrial users rely on both surface water and groundwater.

Nine major aquifers and several minor ones hold groundwater. Texas assigns groundwater rights using the rule of capture, which gives landowners the legal right to the water under their property. Groundwater conservation districts can, however, require well permitting or regulate the pumping and spacing of wells.

Aquifers recharge naturally as rainwater percolates through the ground. Some aquifers recharge quickly; the Ogallala Aquifer does not. The State Water Plan projects groundwater availability will fall 25 percent from 2020 to 2070, partly because of the Ogallala’s depletion.

By comparison, the state owns surface water and grants water rights to users such as cities, utilities, firms and individual landowners. River authorities or watermasters administer water use on some river systems, including the Rio Grande, the Brazos and the Lower Colorado. During a drought, the users with the longest-standing permits tend to take priority.

Regulators manage surface water availability with storm and wastewater capture and reuse, stream diversion and reservoirs. Some metro areas are heavily dependent on surface water. The greater Dallas–Fort Worth area sources 89 percent of its water demand from surface water.

Water demand to grow as economy, population expand

The State Water Plan anticipates water demand increasing 9 percent during the half century ending in 2070, mostly because of population-growth-driven municipal water consumption.

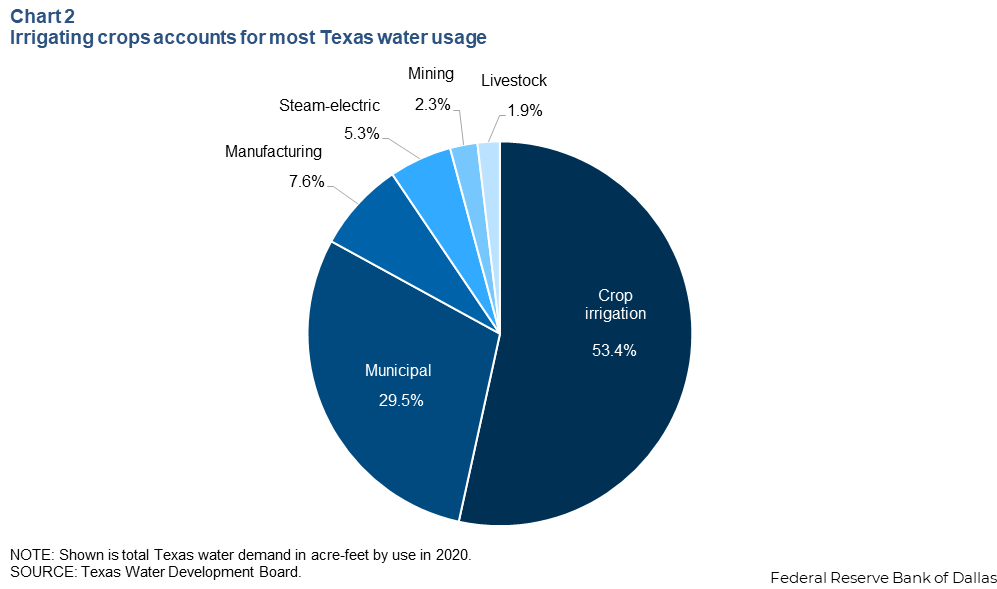

Crop irrigation accounts for the majority of water use in Texas (Chart 2). Farmers and ranchers used 9.8 million acre-feet of water in 2020—mainly groundwater, and much of it from the Ogallala Aquifer.

But as Ogallala resources dwindle—with a replacement economically impractical— water scarcity and costs will rise in rural areas, and crop production may fall. Agricultural water usage is expected to decline 20 percent through 2070, encouraging more-efficient irrigation as well as farmers leasing or selling water to cities or other users.

Municipalities are the second-largest water use category. With Texas’ growing population, municipal water demand is expected to surpass agricultural use by 2060, increasing 63 percent by 2070, according to the State Water Plan.

Water is also used to a lesser extent for manufacturing, power generation and mining. Manufacturers’ water demand is projected to grow 14 percent over the half century. This activity is concentrated along the Gulf Coast, notably among oil refineries and petrochemical plants.

Proliferating data centers also weigh on water demand. Each data center uses enough water to supply a city of tens of thousands. Similarly, legacy power plants use significant amounts of water for steam turbines and cooling. In the future, increasing reliance on wind and solar power could temper the power sector’s water demand.

Oil and gas extraction from shale formations via hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is also water intensive and occurs in dry West Texas. Mining demand, which only accounts for 2.3 percent of statewide water usage, is expected to decline 31 percent by 2070, as fossil fuel production using current technologies winds down.

Expanding the water supply across Texas

Most of the State Water Plan’s management strategies focus on increasing the efficiency of current sources. Conservation accounts for 29 percent of water management strategies by volume. Reuse makes up another 14 percent. Some areas, such as North Texas, deploy man-made wetlands for wastewater reuse. The region’s latest water plan proposes significantly expanding this strategy.

Additionally, Texas could repair and update existing water infrastructure, whose efficiency decreases with age. The Texas Living Waters Project, a consortium of environmental groups, estimates enough water is lost through pipe leaks to meet more than 3 percent of statewide demand. Mitigating this loss would cost about half as much as investing in new water sources, the group says.Water quality issues arise with aging infrastructure and resulting pipe breaks. Water managers issued 2,883 boil water notices on average every year from 2019 to 2023. Indeed, Texas ranked 46th out of 50 states in users’ satisfaction with tap water in a 2023 survey.

Reservoirs are the go-to solution for new water supply

Another strategy to expand the state’s supply of surface water is the construction of new reservoirs. They store most of the surface water in Texas. The Lower Colorado River Authority is building the 90,000 acre-feet Arbuckle Reservoir in Lane City, about 75 miles southwest of Houston. (By comparison, Texas’ largest reservoirs hold 4.5 million acre-feet).

Reservoir construction has high upfront costs, but the large storage capacities and long lifespan allow planning districts to take advantage of economies of scale and smooth natural variations in water supply over time.

Construction requires lengthy regulatory approval, and project costs are high. Often, the land could be used for other purposes and may require displacement of those interests. Additionally, evaporation diminishes supplies—an annual average of more than 2 million acre-feet from 2001 to 2018.

Reservoirs also come with tough distribution choices. During periods of low supply, managers may decide to prioritize municipal needs over agriculture, as the Lower Colorado River Authority has done since 2022.

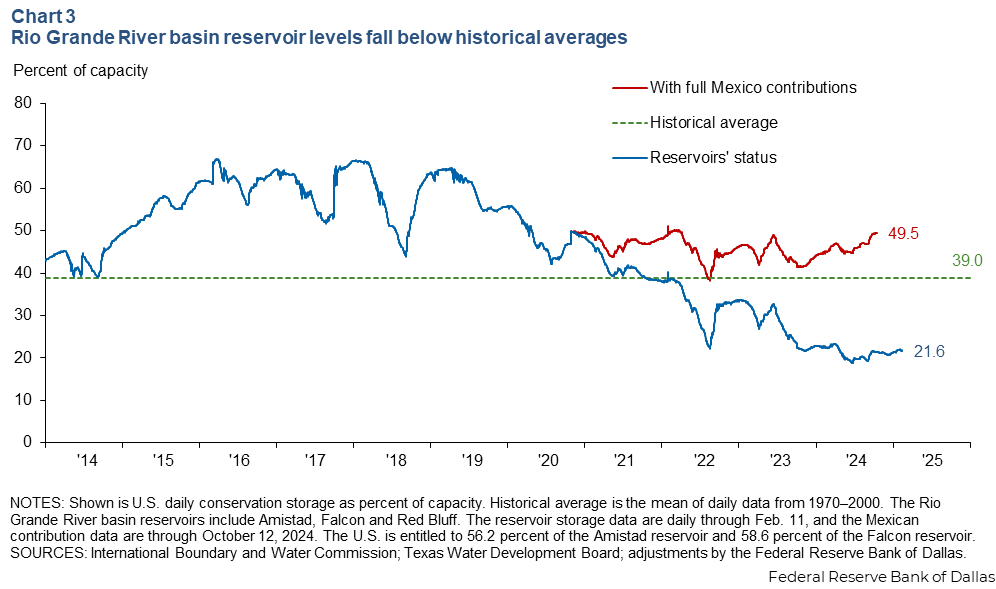

Reservoirs along Texas’ international border face their own challenges. Mexico and the U.S. share the Rio Grande’s Amistad and Falcon reservoirs under terms of a 1944 treaty. However, Mexico has not met the required release schedule in seven of the last 10 five-year cycles, partially due to drought. In the current cycle, Mexico lags treaty amounts by about 1 million acre-feet.

With full contributions from Mexico, the reservoirs would still be below both their historical average and 2017 storage levels (Chart 3). Part of the shortfall is due to lower flows from the U.S. According to the International Water and Boundary Commission, upstream flows from the U.S. side have declined by 33 percent into Amistad and 22 percent into Falcon.

As a result, farmers in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, who depend on these reservoirs for irrigation, face persistent shortfalls. In 2024, the state’s last remaining sugar mill closed. Texas A&M Agrilife researchers estimated that as of 2023, the loss of all irrigation water would cause Lower Rio Grande Valley economic activity to contract by almost $1 billion (about 1 percent of area GDP) and employment to fall by 8,400 jobs. These types of economic disruptions may become more likely as farms, businesses and households adapt to greater variability in water access and cost.

Desalination can be a costly strategy

Some cities have turned to desalination. Texas has 53 desalination plants across the state that process brackish surface water, brackish groundwater and reclaimed water, though not seawater.

In the late 2010s, Corpus Christi, banking on the potential for seawater desalination, committed significant amounts of water to two new manufacturing plants. However, seawater desalination costs $800 to $1,400 per acre-foot (about four times the cost of indirect reuse) and creates significant environmental challenges. The city’s first desalination plant won’t come online until 2027.

Buying groundwater rights secures supply

The potential for future water shortages in Texas is propelling a race for groundwater rights. El Paso spent $222.4 million from 2016 to 2021, buying 70,000 acres 90 miles east of the city solely for the rights to the water below.

With water rights in hand, water utilities can pipe water from wet areas to dry. Two of the largest water providers in the Dallas–Fort Worth area activated a $2.3 billion, 150-mile pipeline from lakes in East Texas in 2022. San Antonio has piped significant amounts of water from an aquifer 150 miles northeast of the city since 2020. Water levels have since declined within the Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer source area served by the Vista Ridge pipeline.

Unfortunately, increasing water supply can come with moral hazard. In the “rebound effect,” residents who see elevated water supplies may feel better about using more, offsetting gains. Customers who view full lakes no longer feel the need to conserve for the upcoming summer.

Attempts to moderate demand growth

Efforts to expand Texas water supply are not enough to close the gap. Conservation is a major strategy in the State Water Plan. For example, together with water reuse, demand management in North Texas will account for 45 percent of new water supplied in 2080.

In areas with acute shortages, local authorities have installed measures to reduce consumption. Texas counties issued around 200 water-use restrictions in 2024, most commonly limiting lawn watering. The counties with the most reported restrictions since 2011 are concentrated around Houston, Austin, Dallas–Fort Worth and the Rio Grande Valley.

Water-use restrictions are a form of rationing. Economists have generally found that raising prices rather than rationing can more efficiently reduce demand and incentivize conservation.

Using prices instead of quotas also preserves consumer choice. Economists Sheila M. Olmstead and Erin T. Mansur find that rationing negatively affects residents’ welfare. For example, some residents prefer to pay more and still water their lawn; others might favor using less indoor water and still watering their lawns.

With Texas’ population projected to expand 73.4 percent, to 51.5 million residents by 2070, no one tactic will provide relief.

Are water markets a possible solution?

Benjamin Franklin famously said, “When the well’s dry, we know the worth of water.”

For many water users in Texas, water is provided free or at a cost below market value, leading to overuse. Economists recognize this as a tragedy of the commons. As in much of the American West, Texas farmers under the Rule of Capture only face pumping costs, a situation speeding depletion of water sources such as the Ogallala aquifer.

For economists, the solution lies with markets that clearly define water rights and set a regional water price, factoring in scarcity.

Texas has some localized water markets, but relatively little take-up. Surface water trades accounted for just 6.8 percent of authorized water use in 2022. The state’s largest groundwater market, the Edwards Aquifer Authority, caps groundwater entitlements and allows users to trade (sell) their rights.

If Texas creates similar water markets, it could raise additional revenue by auctioning initial water entitlements. These proceeds could help pay for conservation and infrastructure improvements.

Ultimately, these water markets are intra-watershed—they require a shared, regulated resource that all can access. If the source runs dry, whether due to drought, upstream factors or unregulated water demand, the system fails.

Additionally, though consumers may wish to source from other basins, the Texas Water Code disincentivizes interbasin surface water trades by forcing users who transfer their rights to forfeit their seniority. Such limitations prevent prices from reflecting the true value of water.

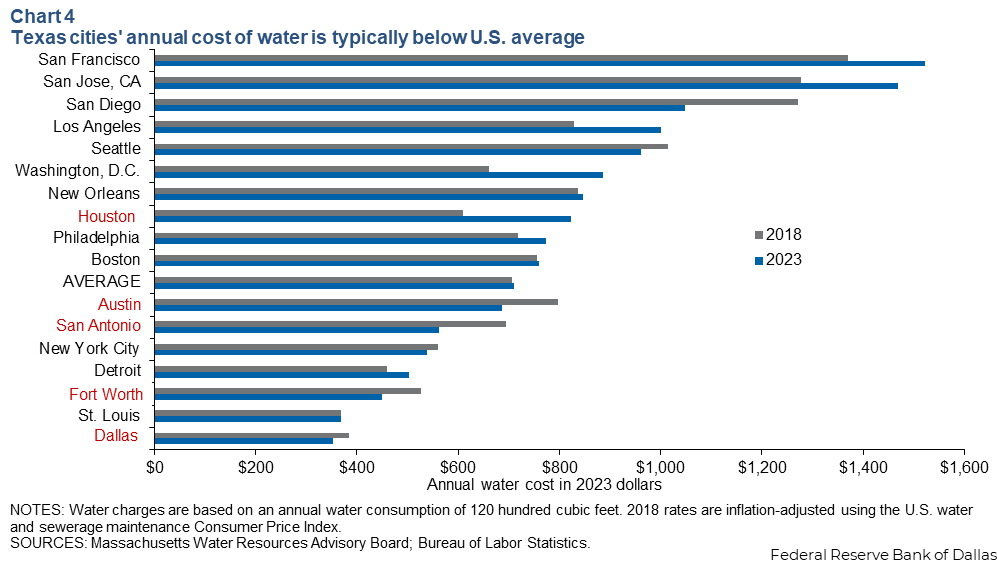

Similarly, even with consumer water bills, consumers do not pay market prices. Water bills in Texas cities largely have remained below average, despite municipal authorities’ attempts to price water to curb consumption, including charging higher rates to heavy users (Chart 4).

Creating a broader water market in the state would let prices signal the true value of water. That, in turn, would more efficiently allocate water from low- to high-value uses, avoid distortionary and ineffective quotas, and motivate investment in water sources, quality and infrastructure. Additionally, a market for buying and selling water between aquifers and watersheds could smooth Texas’ geographic differences in water supply.

Indeed, Gov. Greg Abbott has suggested Houston should sell excess water to the state, which it would then send to West Texas. Lawmakers have discussed a statewide mechanism to transport water as needed—similar to Texas’ electric grid.

Implementing a large water market would require significant infrastructure investment, changes to laws governing water and oversight so smaller towns and rural areas aren’t drained of valuable water.

Growing cost of inaction

There is disagreement over the cost of safeguarding the water supply. To address potential shortfalls, the State Water Plan envisions an $80 billion expenditure over the next 50 years. Texas 2036, a think tank studying state needs in advance of Texas’ bicentennial, argues that the state should also improve its water quality at a total cost of $154 billion over the half century.

This funding shortage is likely to grow. North Texas water officials found that the cost of implementing the 2026 State Water Plan in their region grew by nearly $20 billion relative to the plan five years earlier.

Without changes to policy, Texas faces significant and growing shortages during periods of drought (Chart 5).

The western part of the state—with declining aquifers, low rainfall and limited reservoir storage—may run out earlier. East Texas, with abundant water, likely won’t. A water market could address the disparity, and consumers could focus more on how the price of water will evolve and less on diminished supplies.

UPDATE 5/2/2025: Data about historical water storage levels in Rio Grande Valley reservoirs was corrected in Chart 3 and the text immediately preceding it. Historical water level data and corresponding charts were also updated in Rio Grande Valley Economic Indicators for the third and fourth quarters of 2024.

About the authors