New Mexico fuels U.S. crude oil output, funding for local programs

New Mexico has quietly become an energy powerhouse. State oil production surpassed 2 million barrels per day (mb/d) in 2024, more than doubling 2019 output.

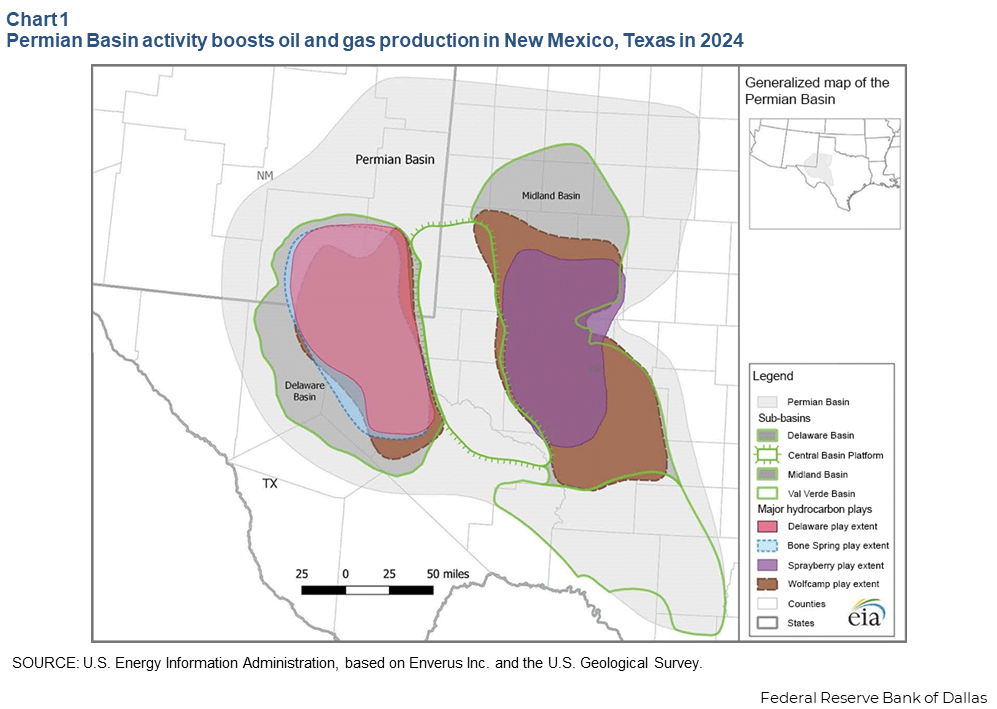

The nation’s leading oil and gas resource, the Permian Basin, extends westward from Texas—No. 1 in oil production—to New Mexico, which is ranked No. 2. Production growth in New Mexico—on both percentage and volume bases—has greatly exceeded its bigger neighbor. Exploration largely in Eddy and Lea counties on federal lands in the southeast corner of New Mexico has propelled the expansion, bolstering state coffers in the process.

The activity contrasts with many other states, including North Dakota, Oklahoma and California, where production has been generally stagnant or declined since 2019. Overall, U.S. oil production has increased, making the nation the top producer globally since 2019. Following the pandemic-prompted energy collapse in 2020, production reached a new peak in August 2023 and trended still higher through December 2024, the latest date for which data are available.

Production in the entire Permian Basin continued to grow in 2024, exceeding 6 mb/d and rising (Chart 1). Industry participants say the region has a larger number of drilling locations relative to other basins and a multi-stacked play, which allows the simultaneous targeting of several oil-bearing zones. It also benefits from a generally favorable regulatory environment, proximity to the refining and chemical complex on the Gulf Coast and access to pipelines for transport.

New Mexico accounts for growing share of well completions

Three sub-basins make up the Permian—the Midland Basin, the Delaware Basin and the Central Basin Platform. The better-performing wells are generally in the Midland and Delaware basins. While operators have been drilling in the Permian since the 1920s, the combination of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (known as “fracking”) achieved during the “shale revolution” has driven growth since 2010.

Wells in the Midland Basin, which is less remote, are shallower than those in the Delaware Basin. They also have lower pressure and avoid risk of buildups of dangerous hydrogen sulfide gas (also known as sewer gas, notable for its pungent rotten egg smell). Initial development during the shale era occurred in the Midland Basin, where existing pipeline and power infrastructure was more readily available.

Oil production in Texas has increased from 5.1 mb/d in 2019 to 5.7 mb/d in 2024, while in New Mexico, it rose from 0.9 mb/d in 2019 to 2.0 mb/d in 2024. More wells are being completed in New Mexico; roughly 20 percent of the new wells brought online in the Permian Basin in 2019 were in New Mexico, increasing to 28 percent in 2023. Overall, 2023 was a record year for wells placed online in the Permian, fueling New Mexico’s production gains.

The industry is also becoming more efficient. Labor productivity (output per hour of labor) in the extraction portion of the upstream oil and gas industry increased 174 percent from 2010 through 2023, compared with an 18 percent improvement in the nonfarm business sector, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

One measure of this efficiency is the number of days it takes to drill and complete a well in New Mexico—down 33 percent from 2019 to 2024, according to data provider Kayrros. While the number of frac crews declined 25 percent in the Permian during the period, operators completed more wells. This occurred despite newer wells’ longer lateral length—a byproduct of improved completion efficiency and technology.

Also, continuing consolidation among exploration and production firms has improved productivity because larger companies—with their stable crews and better acreage positions allowing drilling of the easiest locations first—complete wells in comparatively less time.

Most New Mexico production comes from federal lands

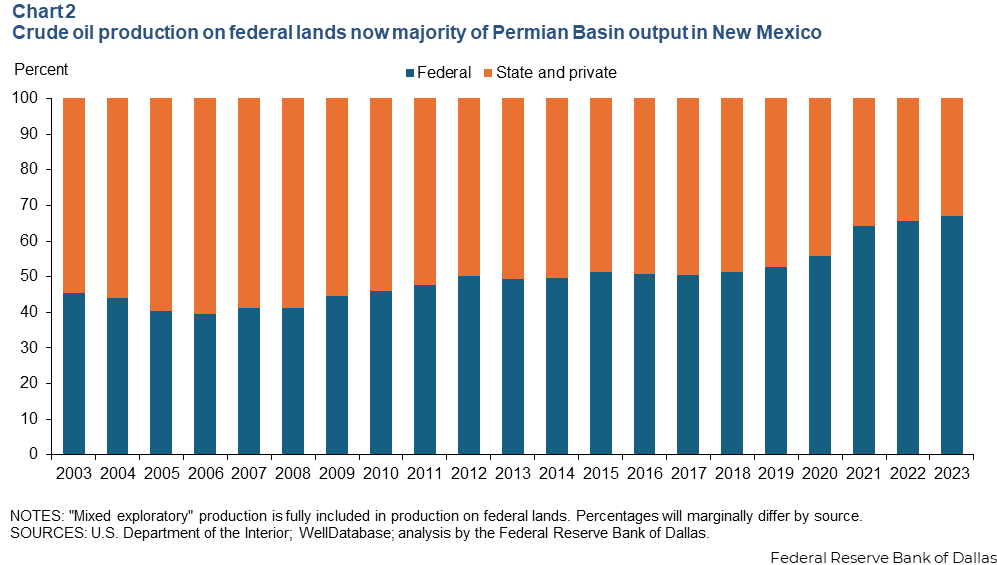

New Mexico oil production comes from lands where private, state, federal or Native American tribes control the mineral rights. Most production in the Permian portion of New Mexico was on private and state lands in the 2000s. However, production on federal tracts started to grow with shale production and exceeded private and state lands in 2015. Roughly two-thirds of crude oil production in the Permian portion of New Mexico is on federal lands (Chart 2). Overall, federal lands account for about one-third of the state’s land mass.

Two factors account for expansion of production on federal lands: greater well productivity and an increasing number of completions.

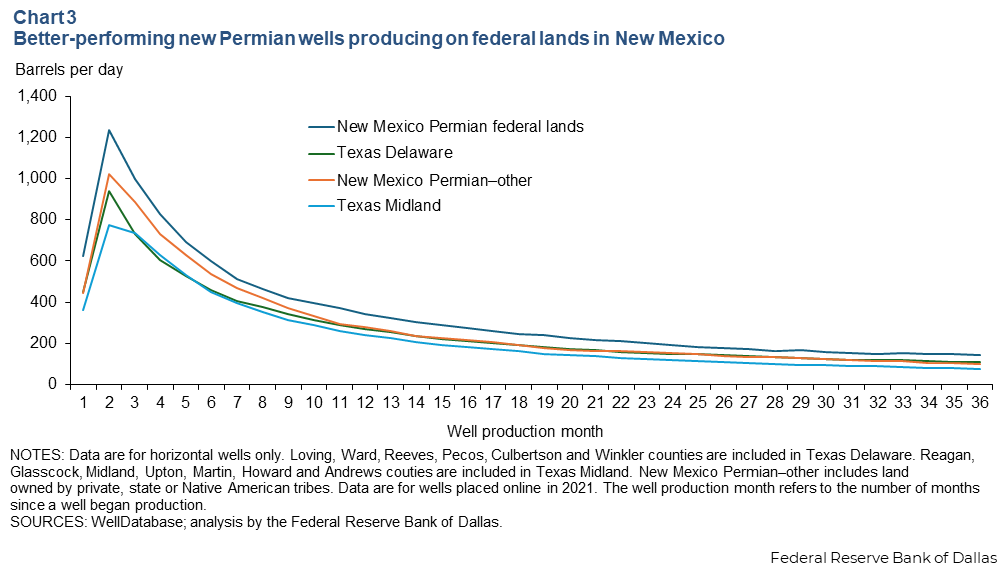

Moreover, the decline curve for wells on federal acreage in the Permian is flatter than for wells on state and private lands (Chart 3). Output from new shale wells generally tends to rapidly decline. Higher ultimate recovery provides more revenue for operators and also allows overall oil production to grow faster since less new output is required to offset declines from older wells.

Also, the share of new wells placed online on federal lands has increased in recent years. In 2019, 51 percent of wells placed online on the New Mexico side of the Permian were on federal lands; that increased to nearly 69 percent in 2023. Much of the shift has occurred gradually with an accompanying increase in the gross number of wells.

From an economics standpoint, wells on federal lands also have lower royalty rates (payments owed to the owner of the mineral rights) than arrangements elsewhere, which may improve well economics. The royalty rate has historically been 12.5 percent on federal lands (though it rose to 16.67–18.75 percent for new leases in 2022). For state lands, royalties are 12.5–20 percent and are also generally higher on private lands.

Potential imposition of setbacks, proposed in a pair of New Mexico House bills, could stymie production growth opportunities. A setback is the minimum distance an oil well must be from certain structures or property lines. Adding setbacks would reduce the number of potential drilling sites and could create regulatory uncertainty, delaying investment. While there are currently no laws requiring setbacks in New Mexico, some counties have required setbacks, although they are smaller than those proposed in the legislation.

Colorado increased setbacks on state and private land in 2018. Oil production there peaked in 2019 and has since declined modestly. Though the exact impact of setbacks is unclear, it is a contributing factor limiting development, according to industry contacts.

Oil and gas revenue bolsters state budget

Eddy and Lea counties—a combined population of 130,000 out of a statewide population of about 2 million—accounted for oil production of about 2.1 mb/d at year-end 2024. Through a combination of production taxes and royalties and bonuses from production on state and federal lands, the two counties’ output plays an outsized role in terms of tax revenue for New Mexico, which provides benefits for residents statewide.

Aggregate tax receipts from oil and gas totaled about $11.3 billion for the 12 months ended June 30, 2024, according to the New Mexico Legislative Finance Committee. Of that amount, the state collected $10.5 billion, and local governments garnered $0.8 billion.

The New Mexico General Fund, the Land Grant Permanent Fund, the Severance Tax Permanent Fund and the Early Childhood Trust Fund are the primary recipients. Oil and gas revenue provided roughly one-third of general fund recurring revenue in fiscal 2024. The remaining three funds took in $6.6 billion in fiscal 2024.

The general fund defrays public education costs, including for K-12 education and the community college and higher education systems. It also supports health and human services, primarily for medical assistance for low-income individuals, but also for early childhood education and care, which was added in 2020.

The value of the three other funds notably increased by $25 billion from June 30, 2019, to June 30, 2024, including investment returns. The Early Childhood Trust Fund was established in February 2020 to tap energy revenue as a stable funding source, with the hope of eventually guaranteeing free, high-quality and universal early childhood care and education.

State Sen. John Arthur Smith, co-sponsor of the legislation establishing the program, said at the bill’s signing that “the riches [they’re] seeing from the oil boom in the Permian have provided … a remarkable opportunity.” The trust fund supplements federal funds for projects managed by the Early Childhood Education and Care Department. They include child care subsidies for about half the state’s children whose families earn up to 400 percent of the poverty level, as well as free meals in low-income areas when most schools are closed.

The current annual budget for the Early Childhood Education and Care Department anticipates several new initiatives to enhance early child care, such as promoting professional development and mentoring of teachers, expanding early pre-K programs and pre-K access to 1,300 additional children and renovating early childhood facilities on Native American lands.

Although the true impact of these initiatives won’t be known immediately, previous research evaluating early childhood investment programs suggest they cost effectively lead to positive outcomes in the future quality of life as well as improved personal behaviors, such as lower drug use and criminal activity.

Lawmakers created the Higher Education Trust Fund in 2024, seeding it with almost $1 billion for tuition-free college for New Mexico residents. The fund tapped monies from oil and gas tax proceeds.

Providing longer-term financial support

New Mexico has the third-largest state permanent fund, behind Alaska and Texas. Permanent funds can serve as a reserve in case state economic conditions change or if oil and gas revenue declines due to lower production or prices.

The funds may be invested in projects to provide longer-term returns for the state. While there is concern that New Mexico oil and gas production could decline, state officials at the New Mexico Consensus Revenue Estimating Group forecast production will increase at least through the end of this decade. While predicting commodity prices is difficult, oil and natural gas constitute about 55 percent of global energy consumption; transitioning from them will likely take many years, if not decades.

New Mexico has capitalized on its booming oil and gas industry to undertake investment policies in education, child care, health care, infrastructure and public improvements. Given that New Mexico has some of the top-performing wells in the Permian Basin, the overall outlook is promising.

About the authors