Plenary Session

Keeping North America Globally Competitive Requires Its Economic Integration

I realize that most people in this audience probably already are convinced and believe in North American (economic) integration. Nevertheless, I would like to present some points of view that maybe you haven’t heard and, hopefully, they won’t be too redundant.

One of the things I teach to my public policy master’s degree students is that we really want to try to train technocrats. People who are going to be basing decisions about policy should do so not on ideology but on evidence and especially on what economists know about how markets work.

I think it is important that we start thinking about our grand strategy for both the United States and the region. While it’s not clear what our grand strategy is, what our role in the world is going to be or what it should be, I think it starts with North America, and I think that’s really important.

I would like to argue—and I think most of you will probably agree with me—that we need to base this vision on the reality of integration that we already have. I know that a lot of the talk yesterday highlighted this: Alonso de Gortari (of Dartmouth College, speaking about supply chains) was one of them, and there were several others, including Christine McDaniel (of George Mason University, discussing the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement).

I’m going to be making the case that integration within North America is not just important because we believe that having good neighbors is important, but also because that integration is important for us vis-à-vis the rest of the world. I’ll explain that as we go along. That’s going to be based on the realization that better neighbors—which are Canada and Mexico, in our case—make us stronger domestically, but also more competitive with the rest of the world. That’s really important in an increasingly integrated global economy. This is a project that I worked on with some folks from the World Bank, Samuel Pienknagura, Chad Bown and Daniel Lederman (Chart 1).

Chart 1

Basically, the argument here is that regional integration makes the region stronger relative to the rest of the world. One of the main reasons is that when you are regionally integrated, your new exporters—people who are trying to enter the export market—can export locally (within the region), and this is how most exporters get started. You start exporting to your neighbors first, and that allows the accumulation of knowledge and expertise that then makes you more prepared to export to the rest of the world. Having a very tight integration in your region facilitates new exporters entering into the global market.

Another reason is that optimal regional input sourcing minimizes costs. I think this is something that we’re all aware of. The option to have different producers within the region allows for cost minimization, and that’s another reason why you become much more competitive with the rest of the world.

Another reason that’s really important is that it allows finance to flow where it’s needed. Our report talks a lot about the integration of capital markets and how having well-integrated capital markets can make up for some of the deficiencies in your own country. One of the big problems that we see with entrepreneurship and getting people started in the export market is lack of finance; this happens in a lot of countries. Having regionally integrated financial markets helps solve some of those problems and allows flexibility and diversity for new exporters.

We also would argue in this report that facilitating worker movement allows us to optimize skill allocation across borders. There’s been a lot of work this year and last year on something called “the place premium.” I published a paper on this as well. Those very large differences in wages across countries create opportunities for migrants that generate efficiency gains. Moving workers from low-wage countries to high-wage countries generates efficiency gains that end up contributing to the economy.

Yet another reason is that promoting regional integration acknowledges the power of gravity. The idea here is that most trade is occurring between countries that are geographically close because transportation costs matter, and there’s a number of other factors that feed into that. The very fact that you have strong regional integration basically acknowledges this power of gravity and proximity—the benefits of proximity—and allows you to take advantage to build up your supply chain or even your own production. The power of gravity is obviously very important, and having regional integration promotes that.

We worry a lot about China, and we worry a lot about competition from other parts of the world. What we don’t always acknowledge is that these other regions are increasingly integrated. Obviously, Europe pursued very deep integration. They formed a market that now rivals the size of North America, rivals the size of the United States. That kind of integration has obviously made them much stronger in many ways. China is increasingly integrated with East Asia—Southeast Asia in particular—and moving a little bit into South Asia. There’s the recent agreement between China and Pakistan. There are other examples of China taking advantage of the differences across countries to integrate, and that makes them stronger. Our lack of initiative puts us behind. Without a clear vision of what we want to do as a region, we’re going to be falling behind.

Let’s talk now about integrated labor markets. Some of the work I did on my dissertation showed that U.S. and Mexican labor are closely integrated and migration, which is one force of that, has changed dramatically. We now know that net flows into the United States from Mexico are negative—more Mexicans are returning to Mexico than coming to the U.S. And there’s also been a very significant change to the demographics of migrants. The main message from this—from my point of view, based on my research—it’s really a mistake to think about the Mexican labor market as a separate labor market from the United States. The Mexican labor market is deeply, deeply integrated into North America. Thinking about the Mexican labor market as a separate market is just simply not factually accurate. It’s one continuous North American labor market.

There are benefits of this either way. Probably a lot of you saw the Dallas Morning News article a while ago, so you’re aware that almost a third of businesses in Dallas are owned by immigrants who only make up 24 percent of the population. Immigrants come in and they start businesses, and this contributes to the regional economy.

Fostering this labor market integration increases economic efficiency. As a result, putting up barriers between us only ends up hurting ourselves, right? Because it reduces the benefits of that integration.

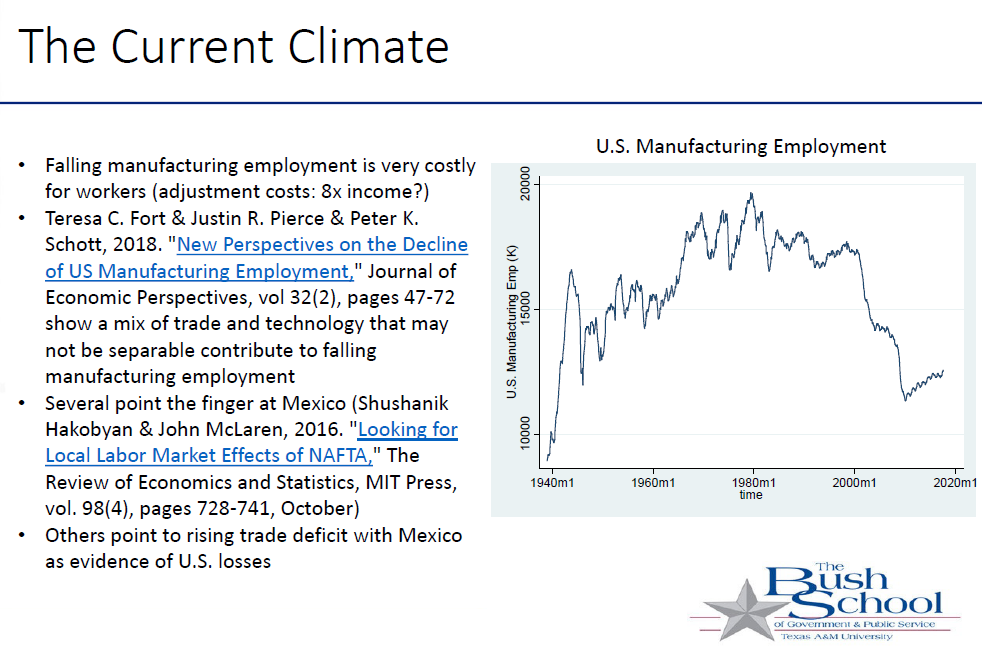

Falling manufacturing employment is very costly for workers, and I think we don’t fully appreciate that. There’s been a lot of recent research in international economics—and I had one paper estimating this cost for Mexico—for the United States and for other countries that shows that when people lose their jobs or are displaced, these events often incur permanent and lasting effects. And these adjustment costs include moving between jobs or between regions and are estimated to be as high as eight times annual income. People don’t like to move, and if they are forced to move involuntarily because they lose their jobs, that’s an extremely large real cost for people.

So, the fact that we haven’t fully appreciated the costs partially explains why a lot of us are mystified by why we’ve seen elections go the way they’ve gone.

Of course, it’s unclear whether the main force behind these changes is trade or technology. If you look at some of the more recent research from Peter Schott, Justin Pierce and Teresa Fort (“New Perspectives on the Decline of U.S. Manufacturing Employment”), they argue that it’s difficult to tell the difference between trade and technology. It’s not like trade is the only culprit or technology is the only culprit; there might be some mix, and the contributors might not be separable. But there have been (other) people—and here’s another paper (“Looking for Local Labor Market Effects of NAFTA”) that points a finger at Mexico—blaming it (Chart 2).

Chart 2

When I was meeting with a congressional representative from Pennsylvania yesterday, he pointed a finger at Mexico and said, “This plant, in my district, left and moved to Mexico. We lost 1,600 jobs, and it was very costly.” We (economists) need to acknowledge that and try to figure out what to do about it. It’s not clear that trade policy is the best way to solve that. It might make more sense to directly address the concerns of these workers than change trade policy. Nevertheless, many others have pointed to the rising trade deficit with Mexico as evidence of U.S. losses, which if you studied international economics, you’d know that that’s not right. That’s not the right way to think about it, but people are very fixated on this trade deficit.

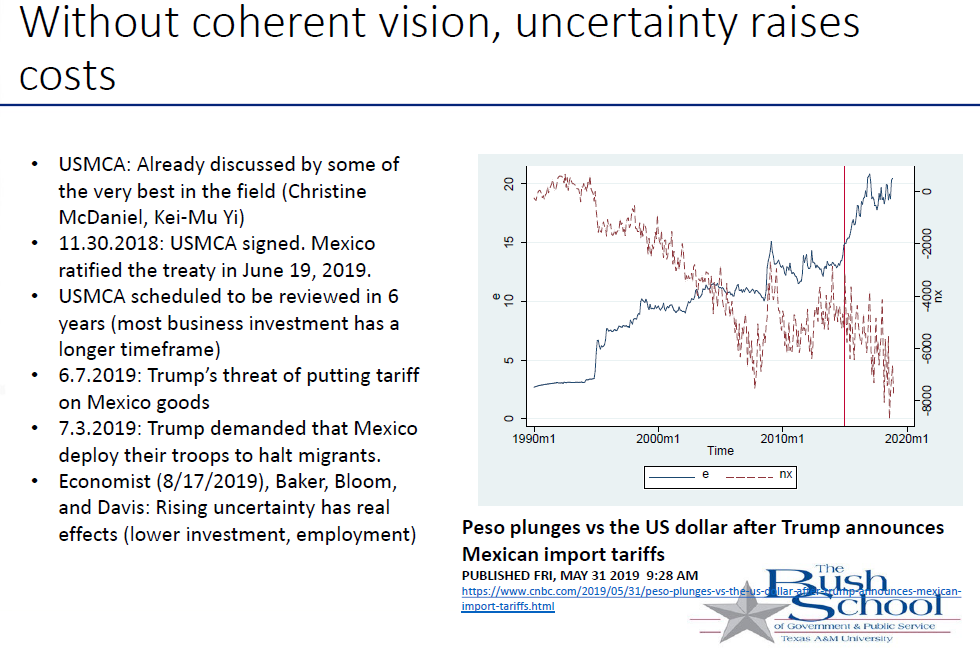

I’d argue that without a coherent vision about trade policy, uncertainty raises costs for businesses and actually contributes to the trade deficit (Chart 3). The trade deficit between the United States and Mexico has gotten worse. But if you look at a very simple introduction to an international economics model, it shows that a lot of that is driven by changes in the real exchange rate. The Mexican real exchange rate has been depreciating. Every time there’s some threat against Mexico, the exchange rate gets worse, or depreciates against the dollar, and that makes the trade deficit worse. Hence, beating up Mexico is actually counterproductive (if you believe the trade deficit is bad) because it depreciates their currency and worsens the deficit.

Chart 3

The next thing, of course, is whether or not U.S. and Mexican workers are competing with each other. That’s the big concern when you talk to representatives from Pennsylvania, for example. They believe that Mexicans are taking U.S. jobs. I have a paper (“Are Mexican and U.S. Workers Complements or Substitutes?”) with the (Mission Foods) Texas–Mexico Center (at Southern Methodist University), where I use labor demand models and econometrics to see how much U.S. and Mexican workers actually compete. My paper shows that before NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement), U.S. and Mexican production workers were actually substitutes.

So, this was a reality before NAFTA happened, but as I’m sure a lot of you heard probably yesterday, the current estimates (after NAFTA) would suggest that U.S. and Mexican workers are now complements due to a restructuring of the North American value chain or global value chains. So, now Mexican workers and U.S. workers are working together to produce different parts of the same output, and I’m going to show you some graphs that represent this. The policy implications here— whether you’re talking about the labor market side or the production side—[is that] North America is best thought of as a common market. It’s a single production unit where we’re working together across the three countries to produce different things.

I’ll give you a real good example of this. After 9/11, we had to shut down our borders for obvious reasons. As a result, several automobile plants in the United States had to close because they couldn’t get the parts they needed from Mexico. The Mexican parts are complementary to U.S. employment. Putting barriers or tariffs or reducing Mexican production reduces the demand for U.S. workers. We can show that econometrically, and it’s also intuitive. This labor demand approach, I argue, works very well to represent the economic restructuring that followed NAFTA and shows that now, particularly in autos but in other industries as well, we’re working together.

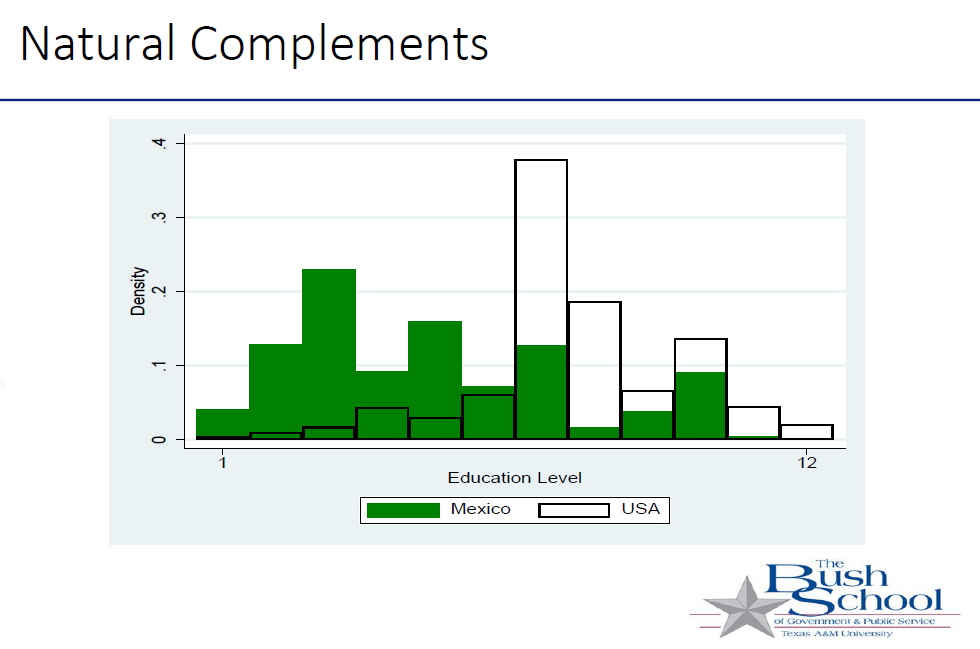

We are also “natural complements.” Chart 4 shows the educational distribution back in 1992 of the United States and Mexico. Mexico is in green; the United States is in white. You can see that we complete each other in the educational distribution in the sense that there’s going to be parts of the educational distribution in Mexico that fill the gaps in the U.S., and then optimal allocation of tasks across these borders increases the demand for workers on both sides.

Chart 4

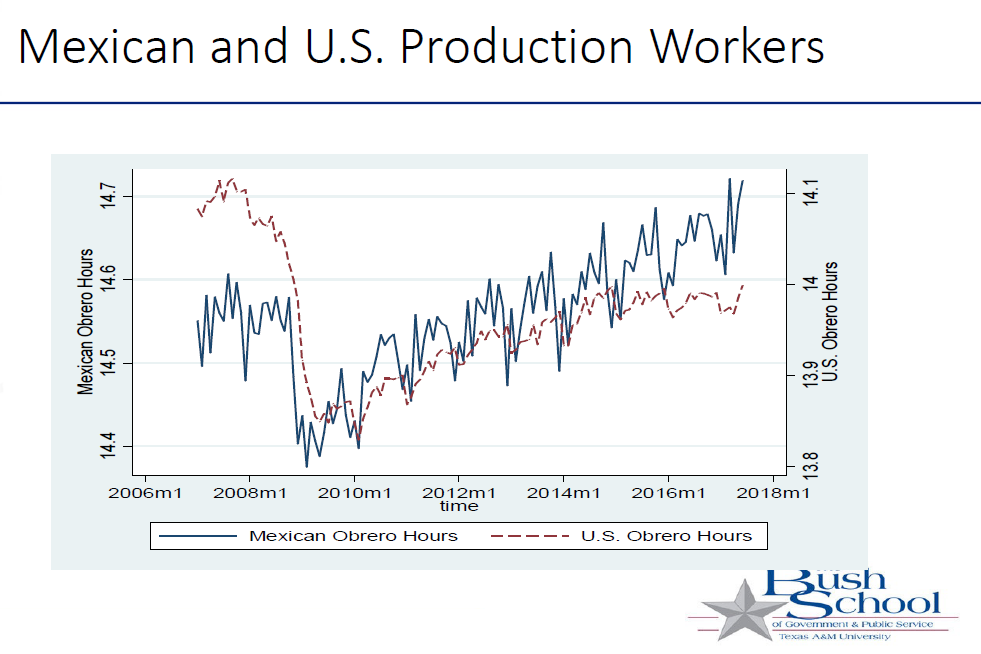

If you look at the graph of U.S. production workers and Mexican production workers over time, they don’t move in an opposite direction, which is what you would expect if we were competing with Mexican workers for jobs (Chart 5). They actually are very closely integrated; they move together. When our employment falls, their employment falls. When our employment rises, their employment rises. You can see from the graph that this happens in the short term and the long term.

Chart 5

The correlation is stronger in some industries than others. It’s not so much true in chemicals because you don’t have much of a value chain in chemicals, and (it’s) a little bit less in food products. It’s very strong in the things you’d expect, which should be industries like apparel and automobiles. If you look at the automobile industry, in particular, North America produced 17 million vehicles in 2018. Mexico produced a very small share of that total. They exported 2.5 million to the United States. While U.S. content in vehicles produced in Mexico pre-NAFTA was less than 5 percent, now it’s more than 40 percent.

The USMCA (United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement) increases administrative costs and domestic content requirements for autos. But having some sort of agreement in place that’s going to facilitate that (trade) movement is really important. The labor demand estimates, like I said, show that (U.S. and Mexican) automobile workers strongly complement one another, and they’re not substitutes. That’s just something most people don’t realize because most people haven’t done the econometrics.

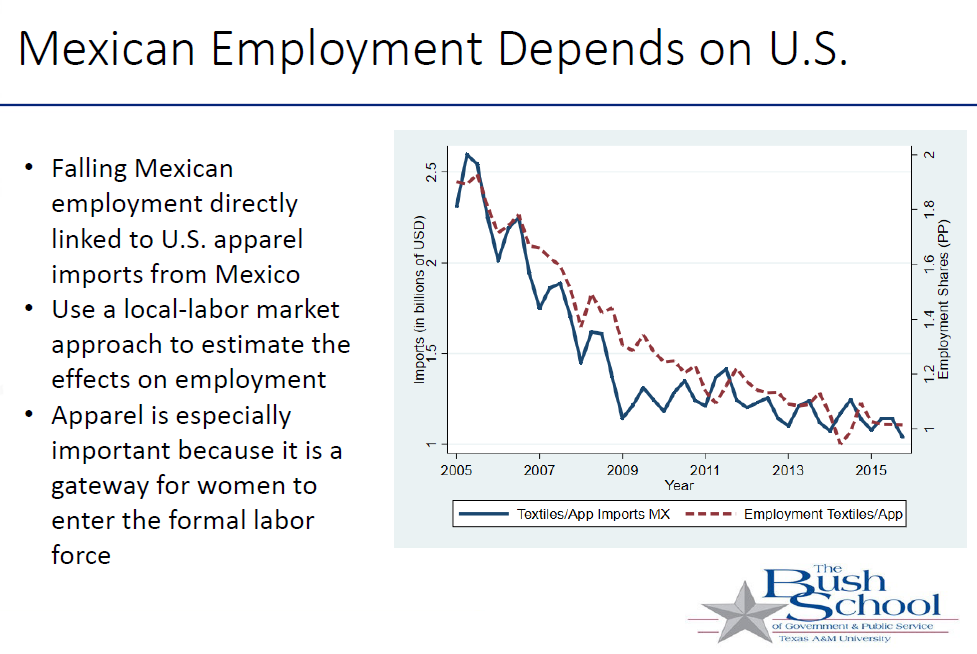

On the flip side, this integration with the United States actually has big implications for Mexico. Mexican employment really depends on the U.S. market. Chart 6 shows Mexican exports to the United States in textiles and employment in textiles. Mexican employment is directly linked to U.S. apparel imports from Mexico.

Chart 6

If you look at U.S. apparel imports in 2000, we imported more from Mexico than from China. But if you look at 2016, the Mexican share almost disappears and the Chinese have greatly taken over the U.S. apparel market. If you look at just the time series graph, as the imports from China have gone up, the imports from Mexico have gone down. When Mexico wins, China loses, and when China wins, Mexico loses. If we’re thinking of a unified North America, and we’re very concerned about China as a competitor, we need to think about how this is also affecting Mexico. Here I’m building on the work of Daniel Chiquiar (of Banco de México), who’s done awesome work on this.

When Chinese apparel exports to the U.S. increase, apparel employment in Mexico goes down. But then these workers leave apparel, and they go into food and they go into leather, and they’re also incurring those adjustment costs. The cost on workers of switching industries is really high, and it’s painful. When I estimated the adjustment costs of changing employment in Mexico, it was an order of magnitude larger than in the United States. Mexicans by these data do not like to change jobs; it’s very costly.

Last week, I was in McAllen (Texas), and I was meeting with the economic development corporation there. They were extremely enthusiastic about the U.S.–China trade war because they believed that it was going to bring in lots of investment to McAllen, and I thought, “That would be great if that would happen.” They actually noted several advantages relative to China: lower shipping costs, Mexican companies maintaining independent operational control, and a lower minimum wage even relative to China. It’s very possible that the maquiladora program might bring competitive advantages. They were very optimistic about the possibility that the trade war would bring investment. We have some supporting anecdotes. For example, Apple is going to be producing its new computer in Texas now, bringing it back from China. There are some (other) anecdotes, and that’s going to be an interesting part for research.

So, what are our next steps along this new path? I think it really needs to be recognized that North America is a single production unit and (we should) support trade agreements and policies that are going to facilitate that kind of integration (Chart 7). I think that’s really important, not just for Texas, but also for the rest of the country—and (we should) recognize that this integrated production makes us stronger relative to the rest of the world.

Chart 7

I think the migration is a critical part of that unified vision, but it’s irresponsible for us not to acknowledge that there are people who are adversely affected by trade, and we need to be better at designing effective compensation mechanisms. We have not done a good job. I mean, that’s been probably the most significant failure in that area, whether it’s in the United States, Canada or Mexico.

We need to review what has worked and what has failed with our current programs and support people, linking them to occupations rather than industries. One of the concerns we had about the trade adjustment assistance that happened with NAFTA was that it was directly linked to industries as they lost jobs, and it wasn’t recognizing the Stolper–Samuelson effects that show that these changes in demand don’t just affect workers in a particular sector. When workers in a particular sector are affected, that ripples out and affects the same kind of workers in other sectors.

Here is another anecdote. It occurred when people were campaigning in Iowa, and they went to the John Deere plant, and John Deere was exporting machinery and lawn mower tractors all over the world. They went to the workers, and they said, “How do you feel about this free trade?” And they were like, “This is a disaster for us.”

But you’re in a company that’s exporting all over the world. “Yeah, but we’re workers, we’re production workers,” and trade can push down and affect production workers generally, not just in particular industries.

We need to understand how the economy works and design assistance programs appropriately to give compensation, because if we don’t, people are going to continue to vote against trade, and they’re going to vote for protectionists, and it doesn’t matter if they’re on the right or the left. I mean, both political sides have protectionist parts of the parties, and we need to try to address that by better helping people who have lost from trade.

And the other final thing, and these are really specific policy proposals, but they did come out in the discussion I was having down in McAllen about attracting this investment. Apple is going to be producing in Texas again, but if we’re going to be bringing in investment from other countries, there are two things that we really do need to focus on. No. 1 is that we really need human resources support programs. I think one of the big concerns that’s holding up Democrat support of the USMCA in Congress is working conditions in Mexico. I have done a huge amount of work on working conditions in the past 10 years. I argue that working conditions are a function of human resource policies.

Human resource policies are a form of technology, just like any other kind of production technology. It’s a technology that can be shared, like helping companies in Mexico, whether they’re U.S. companies, Chinese companies or whatever, adopt what we would consider to be modern human resource policies. We need to facilitate understanding from foreign capital coming in of our human resource policies and why they’re so successful.

The other key point of focus, of course, is identifying the skill gaps in Texas, in particular, and elsewhere based on this vision of integrated production.

What we really mean by that is what the folks down in McAllen were saying: “We can attract this high-tech investment, but we don’t have the skills that we need to work on the high-tech production.” We need to identify what those skills exactly are and then try and help the local universities, University of Texas-El Paso and a whole bunch of others in the (Rio Grande) Valley to train the people to really take advantage of this kind of production.