Panel 3: Energy Sector: Investment, Regulation and Binational Strategy

Lifting Mexican Red Tape Could Speed Energy Infrastructure Growth

Those of you that know me, see me as very bullish on Mexico energy and on cross-border energy. I work in a company that focuses, among other things, on building electricity interconnections between the United States and Mexico. That has exposed us to a lot of interesting situations and opportunities in Mexico, particularly on the electricity side.

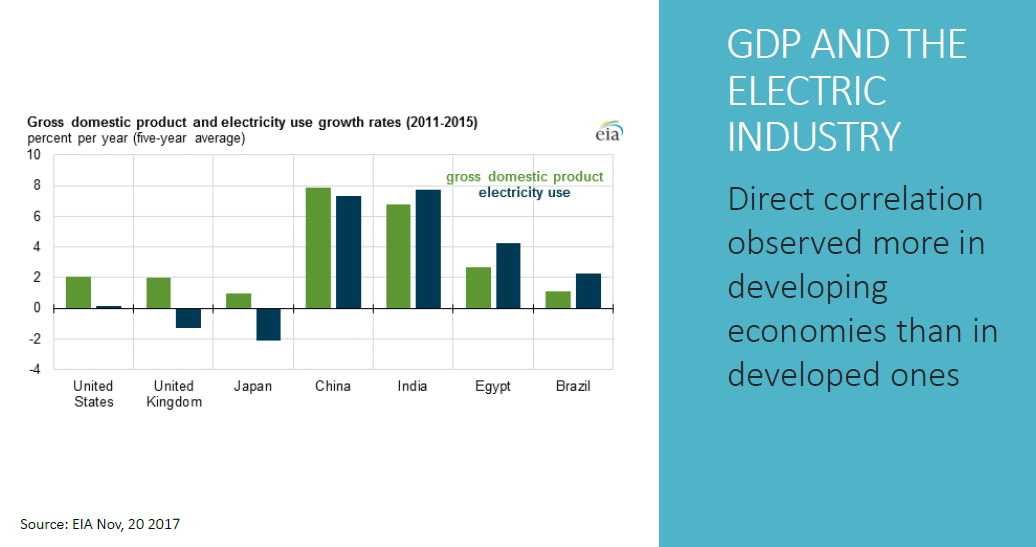

The growth of electricity in developing countries—not developed countries—closely tracks gross domestic product (GDP) growth. If you look at the growth that you’re seeing in Chart 1—China, India, Egypt, Brazil—Mexico is no exception. GDP is directly tied to electricity consumption, or electricity consumption is directly tied to GDP growth. There are many explanations for that.

One, they (countries) grow their demographics, and as they become “richer,” they consume more [goods and services]. Now, they can go more often to the theaters. They can go more to the malls. They can buy more electronics.

Chart 1

Then the population starts aging. It becomes thriftier in how it consumes energy. There’s more energy efficiency. So, in some countries, the GDP growth continues to be positive even as electricity demand decreases.

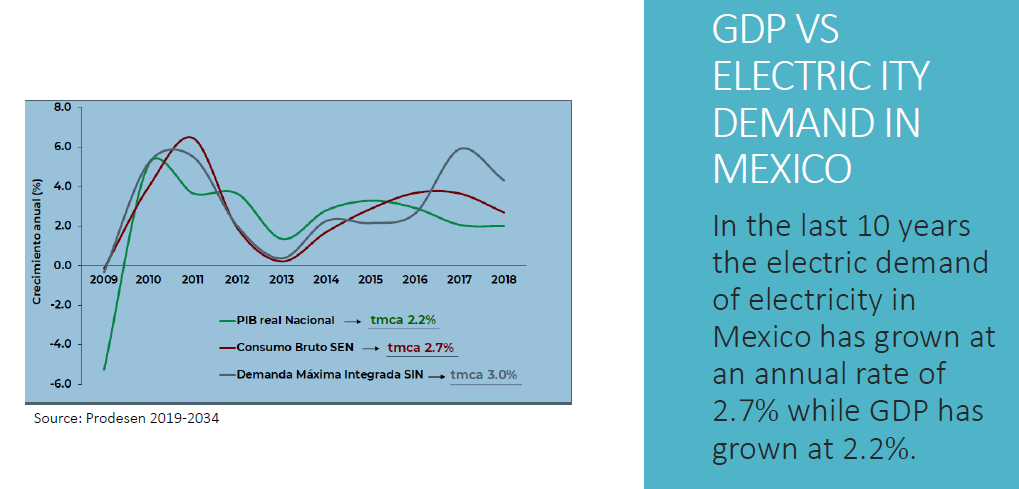

That’s basically what’s going on; Mexico is no exception. In the past 10 years, the consumption of electricity in Mexico or demand for electricity has closely tracked the GDP, as you can see from the graph and, in fact, it has outpaced the GDP in Mexico. Consumption has been growing on a gross basis around 2.7 percent, and the GDP growth in an average per year has been 2.2 percent. As you can see, Mexico is still developing (Chart 2).

Chart 2

That means that the more electricity consumed in theory, the greater the investments that one needs or the country needs [to make] in generation and in transmission and distribution. And whether the investments are done in the country or done outside the country and the electricity is brought in via transmission, that demand and that increase in demand is important to anchor investments. These kind of investments are long term; they’re very capital intensive.

These projections actually are encouraging for those who are looking at the electricity market. At least for the next three decades, the annual projected growth is 2.7 percent. So, it’s still probably higher than GDP growth.

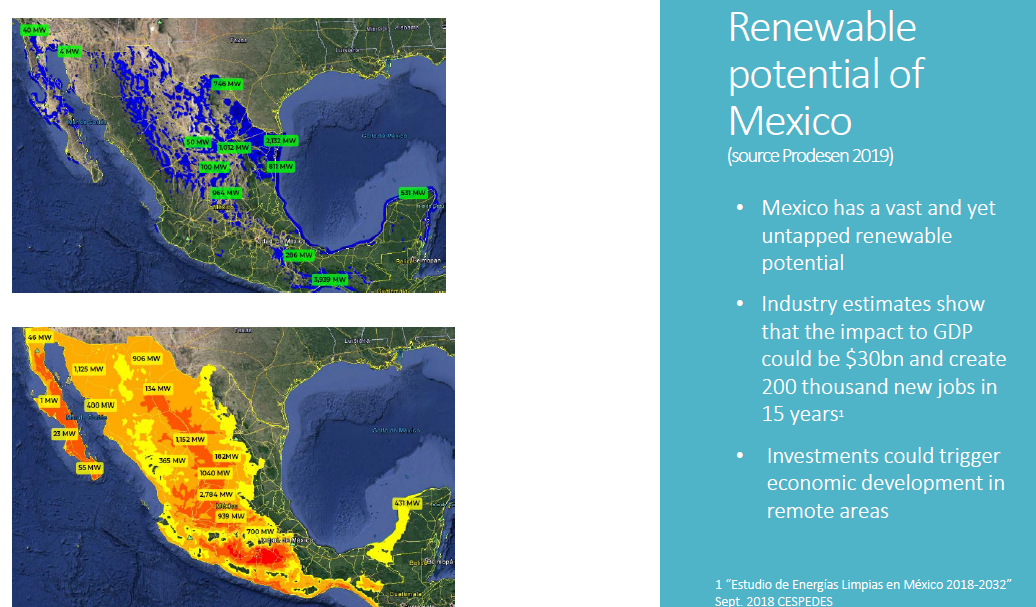

Another interesting fact is that Mexico is a large country; I think it’s the 14th-largest in the world, geography wise. The top panel of Chart 3 shows projects that have either been approved or are in the midst of being approved through the various processes in Mexico, whether regulatory or with interconnection to the grid. The chart also shows the amount of megawatts in the queue or that are being built is in the thousands (Chart 3, blue).

The bottom panel is the solar potential. The sun always shines down there, and in some places, it shines too much. There’s a lot of solar potential in the country. Mexico has a unique opportunity. However, it requires investment to capitalize on its renewable energy potential. Hopefully, they won’t squander it [renewable potential].

Chart 3

As I’ll mention later in the presentation, we’ll see that though some of the current thoughts prevailing in the government circles in Mexico indicate otherwise, [but] the potential is there. The investments that could be attractive just on the renewable side are massive. Most importantly, the jobs and the economic development that they can create are to be reckoned with. For instance, some of you are aware that one of the policies of the AMLO (Andrés Manuel López Obrador) administration is to foster development in the southeast region of Mexico, which encompasses the states of Oaxaca, Chiapas, Tabasco, Campeche and Yucatan.

Oaxaca is one of the premiere wind-generation regions in the world—not in Latin America or in Mexico, (but) in the world. It has as high a potential [equal to] some of the regions that are famous here in Texas, in the (Texas) Panhandle and in North Dakota. Oaxaca is one of the most-impoverished regions in Mexico. If you match the large wind potential and the need for electricity that Mexico has, investments down there could generate a lot of change and economic development.

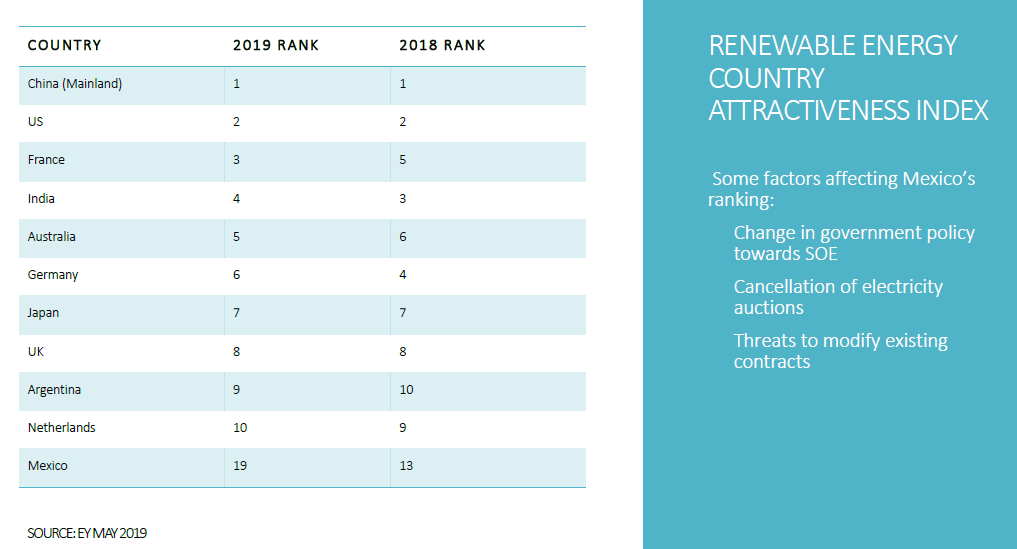

However, things are not going exactly how we want on the regulatory side. Chart 4 shows how attractive Mexico is for renewable energy projects. It is No. 19, falling six places from last year. Some factors affecting Mexico’s ranking are changes in government policy, cancellation of electricity auctions and threats to modify existing contracts.

Chart 4

In 2016, Mexico estimated that it would need about $125 billion to keep up with the country’s needs. That money has to come from somewhere, and that’s where investors outside Mexico and even within Mexico could have a role. That’s where the USMCA (United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement) can help and NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) has helped.

There are two chapters that talk about energy in the USMCA. The first one is Chapter 8.1, basically a Mexico-chapter only. It talks about the sovereignty that Mexico retains of the ownership of hydrocarbons. Basically, the U.S. and Canada are recognizing formally that Mexico can and will own the hydrocarbons in its territory. The other is Chapter 14, which talks about investor protections and the famous investor-state dispute settlement mechanism (ISDS). Some experts argue that the USMCA is a little more limiting than NAFTA regarding ISDS protections.

But when it comes to energy in Mexico, the majority of the projects and the majority of the contracts are going to be anchored by the government, whether it’s Pemex or whether it’s CFE (Mexico’s Federal Electricity Commission). The ISDS will offer protection and [also] offer very clear guidelines on how investors could take advantage of arbitration protections, if needed. That brings a lot of certainty to the investments side on the energy sector because it protects against expropriation risk. That’s encouraging about USMCA.

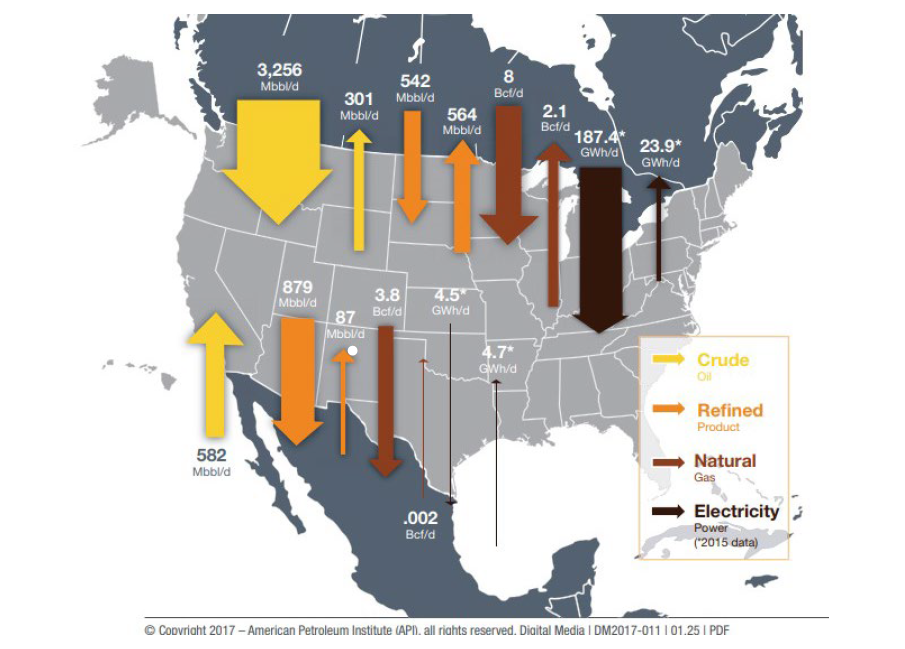

Chart 5 shows how NAFTA has helped the trade of energy commodities. The size of the arrows depicts how much trade is going on. The yellow one is crude oil. There’s a lot of crude coming from Canada and Mexico into the U.S. However, the U.S. is sending more refined products, like gasoline, to Mexico. In addition, the majority of the natural gas that’s being imported into Mexico comes from the U.S. There are some liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports through the LNG terminals on the Gulf and in the Pacific. Mexico rarely, if ever, exports any gas to the U.S.

Chart 5

SOURCE: Reproduced courtesy of the American Petroleum Institute. North American Energy, 2017.

SOURCE: Reproduced courtesy of the American Petroleum Institute. North American Energy, 2017.

Canada has a larger trade balance in electricity. Canada’s electricity exports to the U.S. are mostly hydroelectricity and mostly to the northeast states. The tiny arrow that you probably can’t see is the amount of electricity that gets imported and exported between Mexico and the U.S., and that’s mostly due to lack of infrastructure. There are very few electrical interconnections between the two countries. But hopefully, the USMCA will enable the increase of electricity interconnections between Mexico and the U.S.

Unfortunately, Mexico’s current administration is not aligning public policy and investment objectives. Other countries, like Peru, have investor-friendly regulation that actually attracts a lot of investment in the mining sector and in the energy sector.

In Mexico, we have a misalignment. To be blunt, there’s a misalignment between what the government wants to do and what the investor community wants to do. There’s also an inefficient regulatory framework. You know, we have countries (the U.S. and Canada) again that have—I wouldn’t say pro-business—but more streamlined regulatory environments. You can see how the investment flows easily.

Mexico has as an inefficient regulatory framework, and it has had a lot of turnover in the ranks of the staff in the regulatory bodies. But also, the regulations are incomplete. There are some things that are allowed in the constitution that haven’t been yet put in writing in the form of regulations. There’s a semi-transparent tariff-setting mechanism. One can argue that the tariff is set based on what the government wants to do as a monopoly, and that disrupts the market and makes it an uneven playing field.

Last, but not least, there’s currently an unpredictable government, and I don’t need to tell you how much pain and suffering there is among people who are developing energy projects right now in Mexico and how long it’s taking for them to get a permit and how volatile the situation is. You know, it all depends on the president’s [López Obrador] daily morning press conference.

Well, anyway, that’s what’s going on in Mexico right now. The government has had basic priorities in the energy sector: to strengthen Pemex and the Comisión Federal de Electricidad (the Federal Electricity Commission), which sort of fly in face of the private sector. The private sector wants to be independent, wants to have open markets and wants to invest and get the returns. The current government said that it wants to reduce energy imports and wants to build a new refinery. Nobody sees the logic in that investment.

So, anything that does not fit in the government strategy is sort of put in secondary or tertiary priority by the government. That is generating angst in the investor community. In addition, they [government officials] are basically dismantling the industry’s regulators. The regulatory bodies are understaffed. They were understaffed before, and now they’re in an even worse position.

The most recent high-profile case was the resignation of the director of the environmental regulatory agency for hydrocarbons. He clashed with the secretary of energy, Secretary (Rocio) Nahle, because she wanted to break ground on the refinery project, and they had not finished the environmental permitting. That’s just a taste of what’s going on right now, why perhaps the country is not looking that good. This year, it has stagnated basically, and maybe energy is just a sample of what’s going on.

So, to wrap up, Mexico seems like a country that is like someone who has a Formula 1 (racing) car stuck in the garage ready to go. They want to move fast, they have this world-class driver sitting there, who’s just waiting to go. And then suddenly, we find out that the tires are flat and there are no front tires, and they have asked the driver to push the car to get to the finish line.

We have a car, but it’s incomplete. “So, let’s push it compadre, because we’re going to get there sometime.” Hopefully, they’ll get the car fully furnished, and we can really compete.

I would just say this. There is a saying: “You can’t have something for nothing.” Mexico and the president and the government of Mexico don’t realize that they have to yield. They have to yield somewhat to what the international investment community wants in order to get investment flowing. I hope they realize that because on this side of the border, we want to write checks and we want to invest in Mexico, and sometimes it feels like they don’t want it down there.