Keynote speech

A Pessimistic Optimist in ‘Interesting Times,’ the Era of Globalization

I am an advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. I always have to remind myself to say that nothing I say represents the views of the Minneapolis Fed or the Federal Reserve System.

We also heard two Mexican economists whom I respect a lot—Secretary Guajardo (Ildefonso Guajardo Villarreal, former Secretary of the Economy and Mexico’s USMCA representative) and Dr. Daniel Chiquiar, the Research Director at the Banco de México—giving us views that were very compatible in some ways, but with very different tones.

Secretary Guajardo is something of an optimist, and my friend, Daniel, is a bit of a pessimist. Whom do I agree with? Well, I cannot tell you. That is the problem. I am not restricted from telling you my views on trade policy, as I am about monetary policy. No, I just cannot tell you because I do not know, and I am nervous about that. There is an English saying that says, “May you live in interesting times.” The history of that saying seems go back to the late 19th century, to Joseph Chamberlain, the prominent British politician and statesman who was the father of Neville Chamberlain, the “peace in our time” prime minister.

Chamberlain claimed that the saying was some sort of Chinese proverb, but no one has ever found any evidence for that. It seems he made it up. Even so, it has become known as the Chinese curse, and we are suffering from it. These are interesting times. Let me see if I have this right. I could have titled this talk “A Defense of Globalization.” Or maybe, “Why I’m a Globalist, not a Patriot.” That was meant to be a joke. My father was in the U.S. Navy for 37 years. He was a globalist and a patriot. I do not see the contradiction.

I feel a little bit guilty about not talking more about rules of origin. But we had such a good discussion this morning, I can just step back and take a big picture.

The Industrial Revolution—this is talking about economic history—started over 200 years ago. The really brutal but heartening fact is that for most of the world, the Industrial Revolution has occurred in the past 50 or 60 years. The Industrial Revolution has improved living standards and reduced inequality throughout the world like nothing else has done in the last 200 or 300 years. I’m just going to show you one specific piece of data: Go to the World Bank’s count of how many people in the world live in extreme poverty. It’s at all-time lows in world history.

That’s not to say that what we call globalization has not increased inequality within countries and even across countries in some cases. But if you just take into account that something like one-third of the population of China is middle class by world standards and one-third of the population of India is middle class by world standards, then inequality has plummeted since about 1990.

The United States was part of a movement after the Second World War to really push to cure the problems that had caused the war. That’s why we created the three big Bretton Woods institutions—the World Bank to lend money to developing countries; the International Monetary Fund to try to control the world monetary system and slow down the process of competitive devaluation, which had hurt us so much in the 1930s; and, of course, the International Trade Organization (ITO) to regulate international trade to prevent trade wars. Or you haven’t heard of that?

The ITO didn’t get off the ground. Instead, there was an initial agreement called the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). In 1994 and ’95, GATT was transformed into the World Trade Organization. But for various reasons—disagreements on agricultural trade being one of the biggest ones—it has run out of gas, and now we’re relying on unilateral liberalization and regional liberalization as the drivers of globalization. When I say globalization, I mean all the good things that have happened since the industrial revolutions.

I am nervous about global warming. We have to do something about the climate change, but we also want to keep growing.

I want to talk about the United States a bit. Come on, I have to talk about my own research. I’m a professor. I mean, that’s what I do, research, and I try to convince people of the importance of it. In a recent project, we look at the losses of jobs in manufacturing due to all of the trade deficits we’ve had with countries in East Asia—at the very beginning, Japan and Korea started in 1992. And later, after 2000, with China. They lent us a lot of money that we could use to buy their goods cheaply, and that was a tremendous boon for the United States, but it cost jobs in manufacturing. But nowhere near as many jobs as have been lost because of improved technology.

What I will touch upon is to remind you of the big tension we have. The biggest trade war the world has experienced since the 1930s is the current one we have with China, and I think the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) would have avoided it or at least we would have had allies on our side, and we threw away that opportunity.

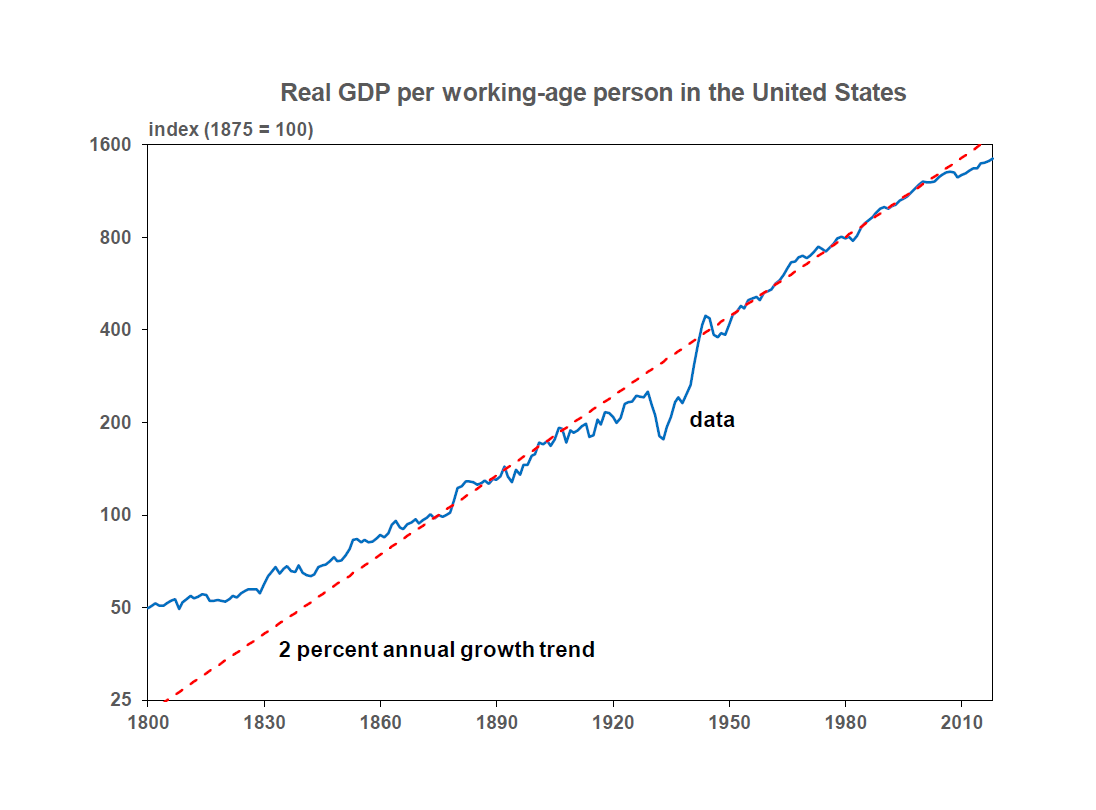

I do not think we are going the right way now. Here is my economic history lesson, and I only want you to see two things here (Chart 1). This is the real GDP (gross domestic product) of people working in the United States. Sometime about 1880, we started growing at 2 percent per capita or per working-age person per year. That is what made us the richest country in the world because, of course, before the Industrial Revolution had started, we were only growing at 1 percent per year.

Chart 1

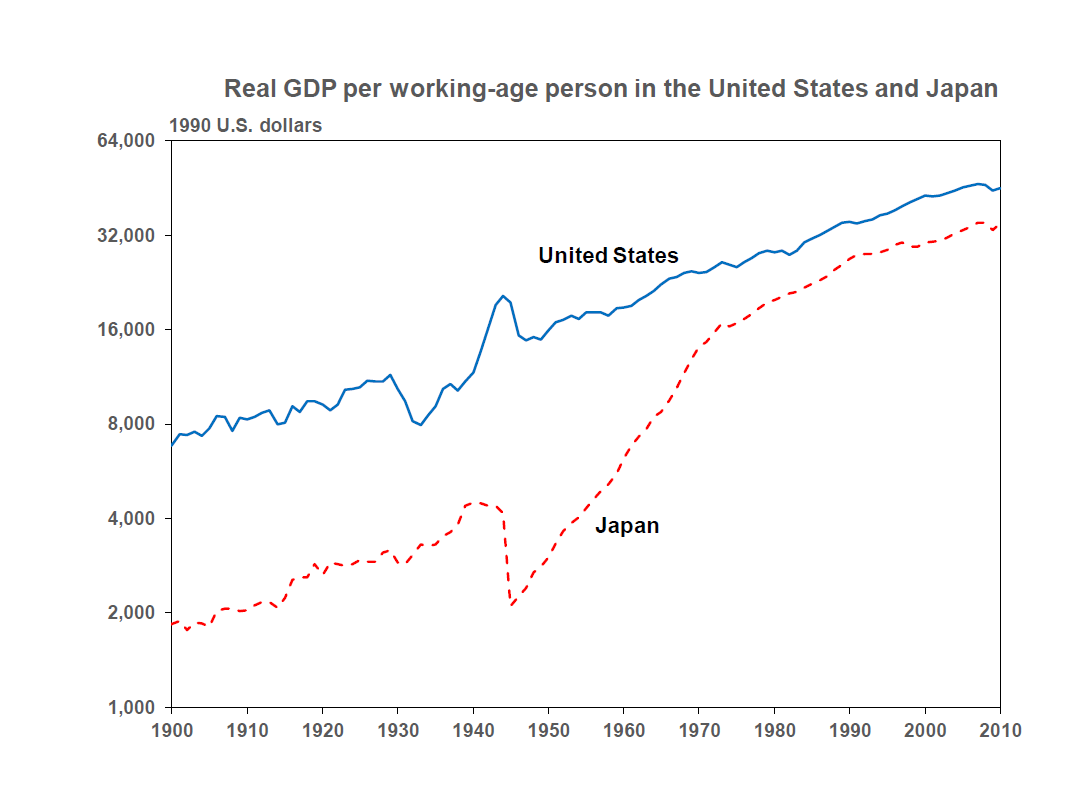

So, here is kind of a theory of economic history that I developed working with Ed Prescott (Arizona State University) when we were studying depressions, but I am still working on it. This compares the United States, growing at 2 percent per person, with Japan (Chart 2). I would get the same picture if I put in Germany, the Netherlands or the U.K. They were poorer than the United States but also growing at roughly 2 percent in the early 20th century.

Chart 2

How much poorer? They (Japan) had 30 percent of the income of the United States. Then we, of course, had our Great Depression and World War II. Japan had the World War II destruction. After the war, of course, Japan was going to grow rapidly. Europe also had its capital stocks destroyed. But they, too, did more than go back to where they were before.

You remember back in the 1980s, we thought Japan was going to overtake us. No, they did not, but they are doing fine. Please do not let yourselves get confused by the journalists and politicians who do not understand economics. When you look at GDP growth, take out population growth. Japan only grows 1 percent per year now, but its population is shrinking by 1 percent. I find it heartening that this Asian country can still keep moving along at 2 percent per capita. We grow 3 percent, but our population is expanding by 1 percent. It is the same 2 percent per capita.

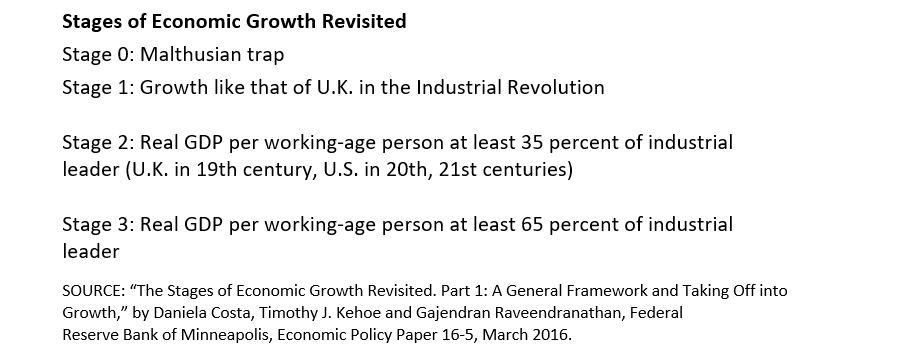

Chart 3 reports on work that I have done with some former students of mine. I was very inspired by Walt Rostow’s work, The Stages of Economic Growth. Rostow was a bit of what we call a Keynesian. He did not really understand growth theory. But he had a clear vision that countries go through distinct stages of growth. You have countries that are stuck in the preindustrial revolution. The economist who analyzed this was Thomas Malthus in 1810, right at the time that his analysis was starting to stop being useful. There were always technological and economic advances, but expansion of the population ate it all up.

Chart 3

Then, we have what Rostow called the “Take-Off into Sustained Growth,” looking like the U.K. at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Rostow thought about this back in 1960, and he was right that achieving sustained growth seemed very difficult. Now, it seems trivial; you do anything right in a country, and you are going to grow.

But then, you want to start catching up to the industrial leader, the U.K. in the 19th century, the U.S. in the 20th century, and get to where real GDP per working-age person is 35 percent of the industrial leader. Mexico has been there. But lots of countries are not there. In fact, that is a fear in countries like China. They call it “The Middle Income Trap.” You start growing and then something is lost. The Chinese are right to be nervous about it.

Then, finally, you do what we call joining the industrial leader where you have at least 65 percent of their GDP—the countries in this group include a lot of countries in Western Europe. In fact, some of those countries in Western Europe do not particularly have lower productivity than the United States. They—just as societies or maybe through their tax systems, whatever—have decided they do not want to work as much as Americans do.

But in Chart 3, I am just looking at countries in 1960 by the classifications I have just given you and you see something that is shocking: In 1960, the majority of the of the world’s population—52 percent—lived in countries that had never experienced any kind of industrial revolution. Now, that number is about 3 percent, and that is what I am saying. The majority of the world’s population lives in countries that have gone through the industrial revolution since 1960.

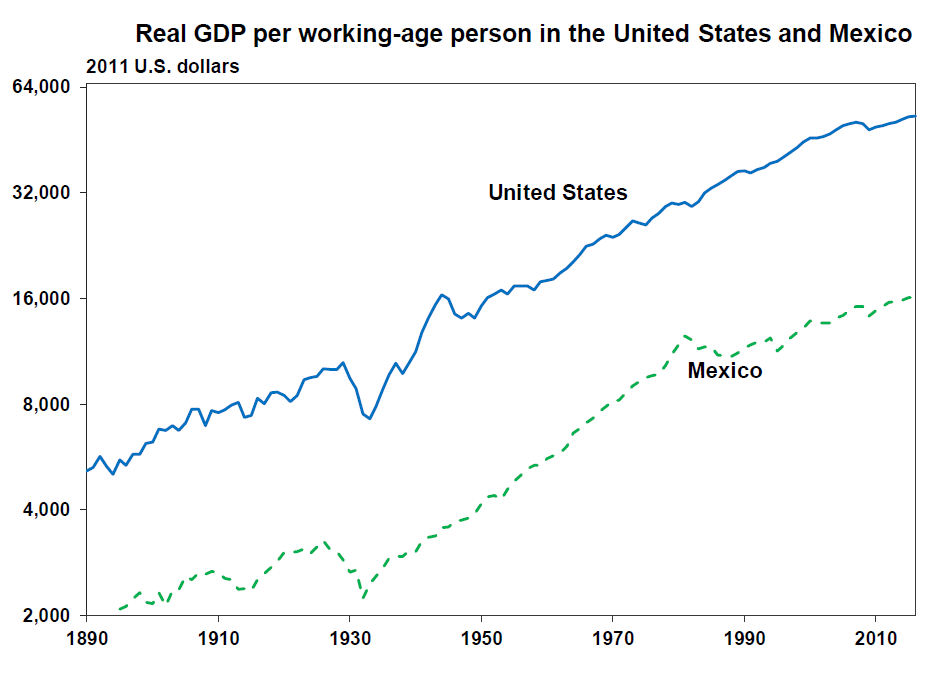

I have to talk about Mexico because I love Mexico so much. But talking about the growth experience of Mexico makes me sad. Between about 1950 and 1980, Mexico was one of the fastest-growing countries in the world. When you take out the rapid population growth, the growth rate was lower, but it was still 4 percent per year. Mexico was catching up with the United States. Unfortunately, Mexico has stagnated since then (Chart 4).

Chart 4

My friend, Kim Ruhl, and I were asked to write a paper in the Journal of Economic Literature some years ago, talking about why Mexico had not benefited from all the reforms that it had implemented. Well, first, we say, “Why did Mexico grow so rapidly?” The answer was three reasons: Urbanization—people moved out of the countryside into the cities; industrialization—a huge expansion of the manufacturing sector; and basic education. Those are the same reasons that China has grown so rapidly in the past 30 years.

Why has Mexico stagnated? You know, I love Mexico. But we have to face the facts. There is a lack of rule of law, financial markets are a mess, labor market regulations are a bit of a mess, and those are the things that we think have held Mexico back. China has similar problems; certainly, in financial markets, China is far worse than Mexico. In terms of rule of law, I would argue that China is also worse (Chart 5).

Chart 5

China is doing well. It is not clear, however, that China has reached the level of Mexico yet. That is something to keep in mind. A significant difference between Mexico and China is that Mexico, when it was in its boom, was closed. We remember from our Mexican economic history that the boom was the period of Mexicanization, when the country was closed to foreign trade and investment. I am optimistic about the future for Mexico. I am optimistic about Mexico. There are just the problems to be overcome.

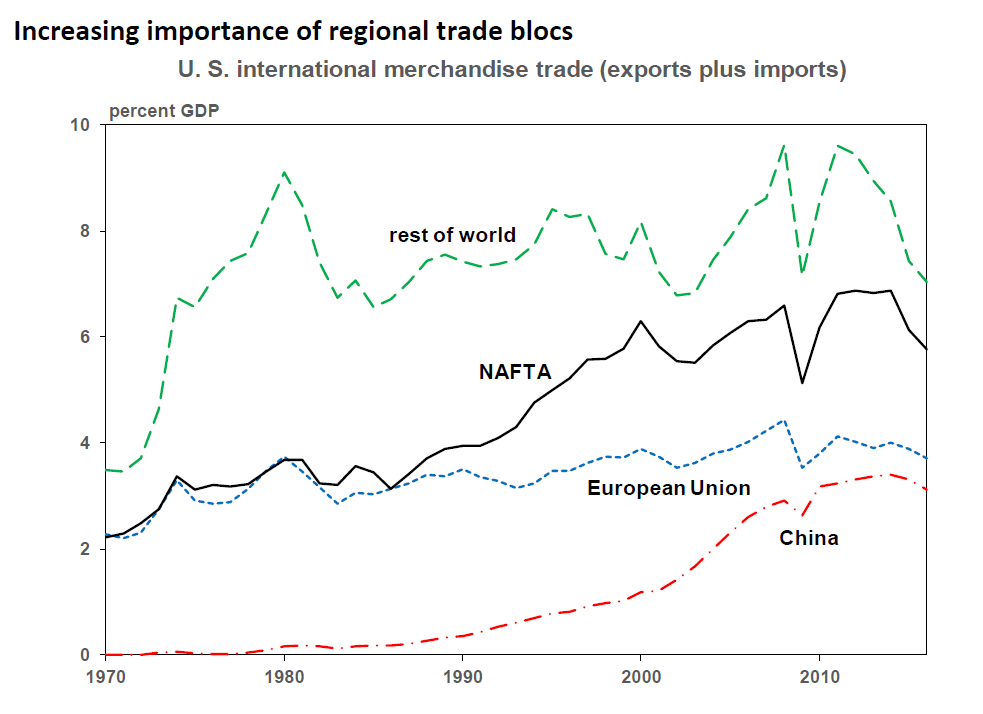

What about world trade? I did not mention one of the essential things in this picture that we always have to keep in mind. Looking again at Chart 1, we see that, except for the Great Depression and the World War II boom, the blue line is almost the red line except at the very end, following the 2007-to-2009 so-called Great Recession. There was nothing great about it. It was just global, and it affected all the countries in the world. What we see in Chart 1 after 2009 is shocking. We have never really recovered from the 2007–2009 recession. The U.S. economy is doing about the best of any major economy in the world right now, and for the last year or so, the labor market has tightened. But in general, we are not back. We are on a growth path about 10 percent below where we should be. And trade has stagnated in the United States because it collapsed during the global recession. It is the same picture for the whole world. Whom do we (the U.S.) depend on for trade? I tell you: It is Canada and Mexico and China. They are currently one, two and three as our trade partners. I do not think we can afford a trade war with China. We certainly cannot afford a war with all three of them (Chart 6).

Chart 6

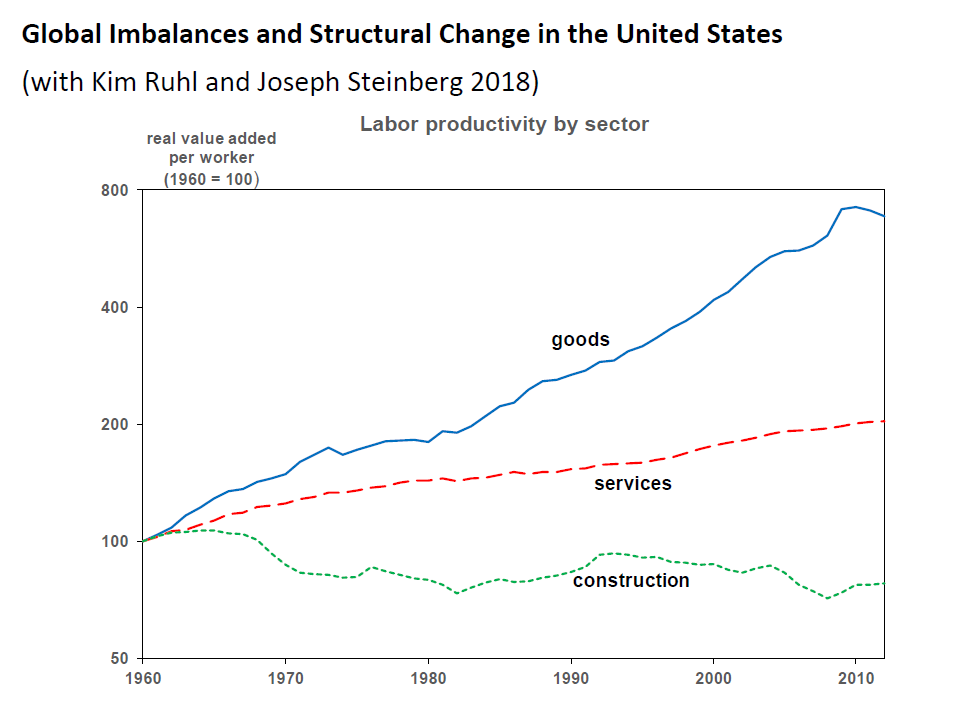

What about the impact of deficits? These are simple facts. I published a paper with my friends, Kim Ruhl and Joe Steinberg, in the Journal of Political Economy last year (2018), and we were looking at what we called, “global imbalances,” and that meant the huge deficit the United States had with Japan, Korea and China. Here are just facts about labor productivity (Chart 7). Productivity in producing goods has grown at about 4 percent per year. Some people will call that “automation.”

Chart 7

Suppose we stick that into a model of trade. We make the assumption in the model that, for some reason, the Chinese, when they get our dollars for their manufactured goods, do not want to buy our goods but rather they want to buy our government bonds. That is something we have to remember about China. We Americans seem to want to have government deficits. Somebody has to buy our bonds. Thank God for the Chinese.

Our model does a very good job with hardly any other driving forces besides foreign savings, mostly Chinese savings, in the United States in it. The model has constant productivity growth, no recessions, nothing but foreign savings in the United States. What happens to employment? What has happened in employment is what would have been there even without what former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke called, “The Global Savings Glut.” For some reason, the Chinese want to save in our country, which in principle is good for us, not bad. The loss of jobs in manufacturing is from our productivity increases.

What about trade and services? In measured trade in services, the U.S. is by far the world’s largest exporter of services. Everybody has a story. They call their bank credit card company, and they talk to some guy who identifies himself as John but might slip up, and you hear his Indian accent and his is name is Sanjay and so forth. India as a country has more than a billion people, and the educated people speak English. We get them to work at call centers. That is good for us and is good for India’s economy.

India exports services, but we export a lot more. We export business services. The world’s giant multinationals are headquartered in the United States. We do managerial services, design services, research services, and we also get all the income associated with copyrights and trademarks in entertainment, pharmaceuticals and so on.

Let me just give you an example that is simplified. General Motors U.S. sells design services to GM in Mexico. That is export of services. You do not find the exports from the United States to Mexico in the data. Actually, you can find it, but you have to know where to look. Whom does GM Mexico pay? They pay GM Bermuda. Why? There’s no corporate income tax in Bermuda. How do they do that? It is really simple. All GM U.S. sells its patents to GM Bermuda. They sell the patents cheap, and some of them end of being worth nothing because they never get used. This is something you can do. GM U.S. sells all its patents to a wholly owned subsidiary in Bermuda, and that is whom Mexico pays. Corporate income taxes are high in Mexico, and before the tax reform, of course, in the United States. So, it is just a way of GM saving its money tax-free, like a 401(k) plan for big corporations.

The money is going to somewhere where the corporation does not have to pay taxes, and sometimes it involves three different entities. Kim Ruhl was explaining a lot of this to me in detail, and I did not quite understand all of it. But that is part of the point. And it is all legal. That is the way many U.S. corporations are minimizing their tax burdens, but it means the published numbers on bilateral trade deficits mean much less than some people in the current administration acknowledge.

Final point: The Trump administration is very right—but it is a complaint that goes back before them—regarding problems that countries like the United States have with China. U.S. firms want to get into China. China has the biggest and one of the fastest-growing consumer markets in the world. The Chinese had a formal system back in the 1990s. If you were a foreign company and you wanted to set up operations in China, you had to have a Chinese partner, and you had to share your trade and technological secrets with that partner. China then joined the WTO, and people pointed out, “Chinese government, your policy is in violation of WTO.” The Chinese government said, “Fine.” They erased the policy, but they still enforce it.

We have got to do something about China coercing foreign companies operating there to give up trade and technological secrets. My own view, perhaps the globalist view, is that we should have been doing this with our allies rather than resorting to a trade war, working through the WTO.

In conclusion, I want to be optimistic about the future like Secretary Guajardo, but sometimes I end up being a pessimist like Dr. Chiquiar.