Panel 2: Services and Trade

Digital Economy Finds a Home in USMCA Provisions

The USMCA (United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement) can help create a North American digital free-trade zone. Even as we build border walls, people can jump them by using electronic means to participate in commerce across North America.

Services were left out of international trade agreements until the 1990s. It’s not surprising then that, during the last century, trade in services across borders did not grow as fast as trade in goods. No one thought to add services to the international trade regime because people thought that services could not, for the most part, be traded across borders. The only way you could consume a service was to actually travel to that place—go get your hair cut in that place—to engage in trade in services. But of course, the electronic medium allows us to now deliver services across borders, often in real time without the buyer or seller leaving home or work. The electronic medium has made many services tradeable.

NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) was one of the pioneering interventions in the space, creating a liberalized trading center for services across the U.S., Mexico and Canada. It offered national treatment; for example, Canada promised that it would treat an American or Mexican services provider operating in Canada at least equal to a Canadian service provider.

There were exceptions and grandfather clauses, but overall, that was the big picture in regard to NAFTA’s innovation. The WTO (World Trade Organization) created a year later (1995) picked up on this. It globalized this desire to liberalize trade in services, but it did so in a much more limited form than NAFTA. The USMCA now takes that NAFTA intervention from 1994 and reinvents it for the digital age.

Tariffs and taxes can interfere with cross-border e-commerce. The USMCA raises the de minimis thresholds at which imports into a country are exempt from taxes and duty fees. Such de minimis thresholds are designed to make relatively low-value cross-border transactions cheaper, faster, easier and more predictable. This directly impacts the ability to engage in e-commerce across borders especially for consumer products.

Another critical thing that USMCA does with respect to duties and customs is the prohibition of duties on stuff sent electronically. If you buy a music CD in the U.S., and you bring it to one of the NAFTA countries, you would have to pay duties. However, if you buy it via iTunes, you will not pay duties.

We first saw this approach in the WTO, with the Declaration on Global Electronic Commerce adopted by the WTO’s Second Ministerial Conference in May 1998. This has now been adopted in the USMCA—prohibiting customs duties on digital products. This means essentially that you can now sell these digital products, music videos, e-books, and software across these three countries—that is, across the continent, without having to pay customs duties. It’s possible that you might have paid sales taxes, which are different than customs duties, but the taxes have to be applied equally to domestic sellers and foreign sellers.

USMCA also prohibits data localization measures. Data localization is the idea that data is only safe if it’s kept in this country. That is, data becomes unsafe, insecure or is unavailable for government purposes if it leaves the country. It’s associated with the idea that data is the new oil, which is the term that you’ve heard many times. It is a metaphor that serves only to cloud the way that data is actually utilized by multiple parties.

It’s worth pausing to reflect on that claim. There was a recent New York Times op-ed arguing that data is the new oil and we should regulate it as such. The reality is that you’re producing a ton of data all the time, but most of it is not very valuable. Data only becomes valuable after it’s analyzed. You might have tons and tons of files in your file drawer, but they are not valuable until they are analyzed. Data isn’t inherently useful—a computer could spin out as much data as you want. It’s very different than oil, which can be readily processed into something that society values.

Data localization is motivated by a number of different possible concerns. One, if the data leaves our country, it will be subject to foreign surveillance. That’s a common concern you’ll hear from governments: “We’ve got to keep this local, so that we don’t have to worry about foreign governments accessing it.” This was a concern raised against the U.S. especially in the wake of the (Edward) Snowden revelations (regarding National Security Agency practices), which suggested that the U.S. was widely surveilling electronic information.

Of course, the Snowden revelations also revealed that the U.S. was surveilling activities outside the U.S. Foreign surveillance doesn’t only happen when on the shores of the government that is doing the surveilling. In fact, a lot of surveillance happens in other countries, and so, with the electronic medium, exfiltration of data, hacking, etc., as we saw in the 2016 elections, this surveillance did not have to take place in the U.S. itself. American data did not have to be abroad to be hacked from Russia. This idea that by keeping it here, you rid yourself of foreign surveillance is, I think, misbegotten.

A second motivation for data localization is the idea that keeping data here is the only way to protect our privacy. When the data moves abroad, it becomes public in some way. The same notion arises in the context of any kind of activity that you might think. You can imagine a kind of food version of this. We can only eat food that’s grown in the U.S. because only food grown in the U.S. is safe. In reality, it turns out that food grown elsewhere is safe, and also that food grown in the U.S. can be unsafe.

A privacy breach can occur domestically, so data might not be particularly safer if we keep it here. In fact, requiring data localization often increases privacy risks because you have to create huge data infrastructures across the world and replicate them in every country where you need to localize to provide services.

An argument is made that by keeping the data here, you generate local employment, and you’re supporting a local digital economy. The problem with that argument is that much of the digital economy actually works by relying upon services provided by others. If you’re opening a new startup, you don’t buy your own server, you don’t buy your own financial management systems. You don’t manage all that yourself. You outsource everything. By not allowing outsourcing to other countries, where your data can be processed, you actually hamper your local startup economy. You now have to rely on local, pricier options that are often not as good as the global versions of that service.

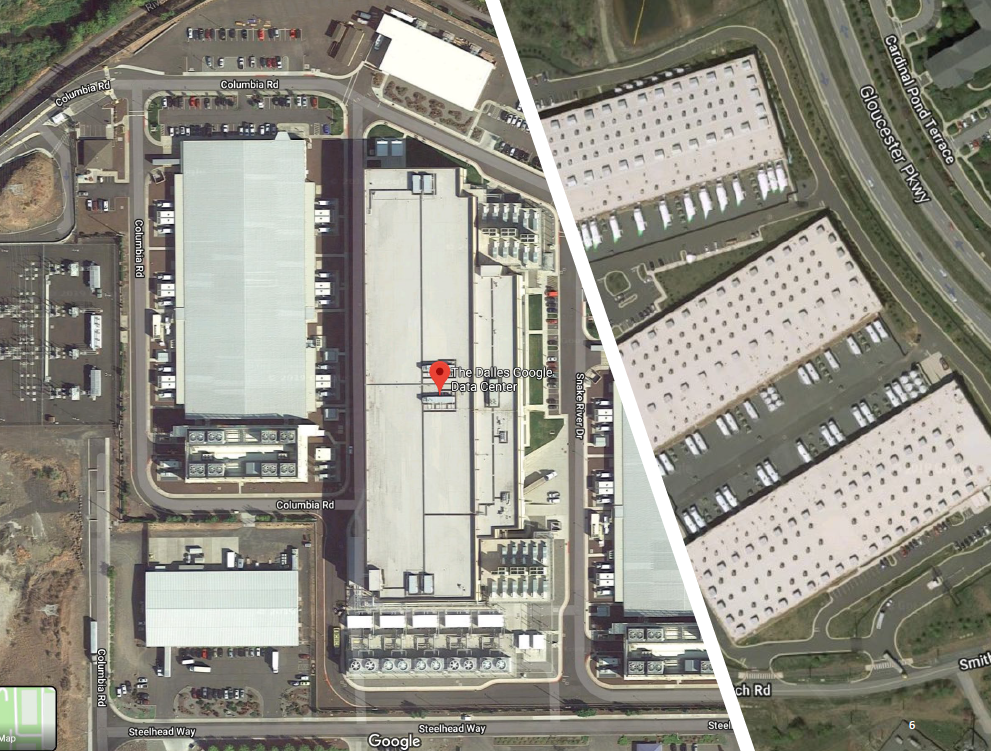

Chart 1 shows images of server centers or server farms. The left one is a Google farm on the West Coast, in Oregon, and the right one is AWS, the Amazon servers, in Herndon, Virginia. One thing you’ll notice about these facilities is that, despite their enormous footprint, there’s almost no parking. It’s just machines talking to machines. There isn’t much in the way of employment in these places that are stuffed with electronic equipment. Unless your country is the one producing that electronic equipment, all that is being imported from somewhere else. Finally, these centers are enormous energy consumers. Thus, it makes sense to sell/export data services to other countries with high energy cost and a lack of infrastructure.

Chart 1

SOURCE: Chander Anupam (made using Google Maps), (2019). “Creating a North American Digital Free Trade,” Forging a New Path in North American Trade and Immigration, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Dallas, TX.

SOURCE: Chander Anupam (made using Google Maps), (2019). “Creating a North American Digital Free Trade,” Forging a New Path in North American Trade and Immigration, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Dallas, TX.

USCMA says data localization is not generally permitted unless it is both necessary and proportionate. In the USMCA, there’s actually a sophisticated provision for data localization in financial services (Chart 2). Basically, what it says is: If you can’t ensure that local regulators, like the Federal Reserve, can access this information when they need it in a timely fashion, then we might insist that you keep it locally. But if you can make arrangements to have this information made available wherever it is back to the regulators on an as-needed basis, then it can travel abroad, and it can be held abroad. USMCA has, I think, a better view of this than earlier exclusions of financial services entirely from the realm of data localization liberalization obligations.

Chart 2

Chart 3 summarizes a few more points about digital trade in the USMCA. There’s information about authentication, electronic signatures, enforceable consumer protections and anti-spam rules. There are limits on a disclosure of source codes and algorithms. The motivation there is that companies don’t want to disclose how their algorithms work to governments because they are worried about industrial espionage.

Chart 3

A critical move on this front is limiting the civil liability of internet platforms for third-party content. This borrows from the Communications Decency Act Section 230 that many of you may have heard about in the U.S. This is a key pillar of U.S. internet law, one of the reasons for our unique success in creating the internet platforms that we have today. Section 230 is the 1996 congressional statute that provides legal immunity to digital service providers for the third-party information they disseminate.

Companies across Canada, Mexico and the U.S. will benefit from these provisions under the USMCA digital chapter, allowing them to enjoy the benefits of economies of scale by having access to digital service suppliers from all three countries. Consumers now have greater access to a broader range of suppliers, and businesses also benefit from having their business inputs from a broader range of suppliers.