Panel 3: Energy Sector: Investment, Regulation and Binational Strategy

Meeting Mexico’s Demand for U.S. Natural Gas Depends on Adding Pipelines

I thought I would begin with a brief overview of the macro picture for LNG, or liquefied natural gas, and then dive into the United States–Mexico relationship as it relates to natural gas and LNG. The macro outlook looks very bullish for global LNG. The demand for gas is growing much faster than for any other hydrocarbon.

Natural gas is cleaner burning certainly than oil or coal. There’s ample supply, it’s cheap, it has a high energy content, it’s relatively easy to move and to store. There are many environmental and economic benefits that are feeding the demand growth. When you see a continuing trend of natural gas and renewables displacing coal and oil for power generation, in particular, that’s bullish for those involved in the supply chain—including my company, GasLog—in LNG transportation and storage.

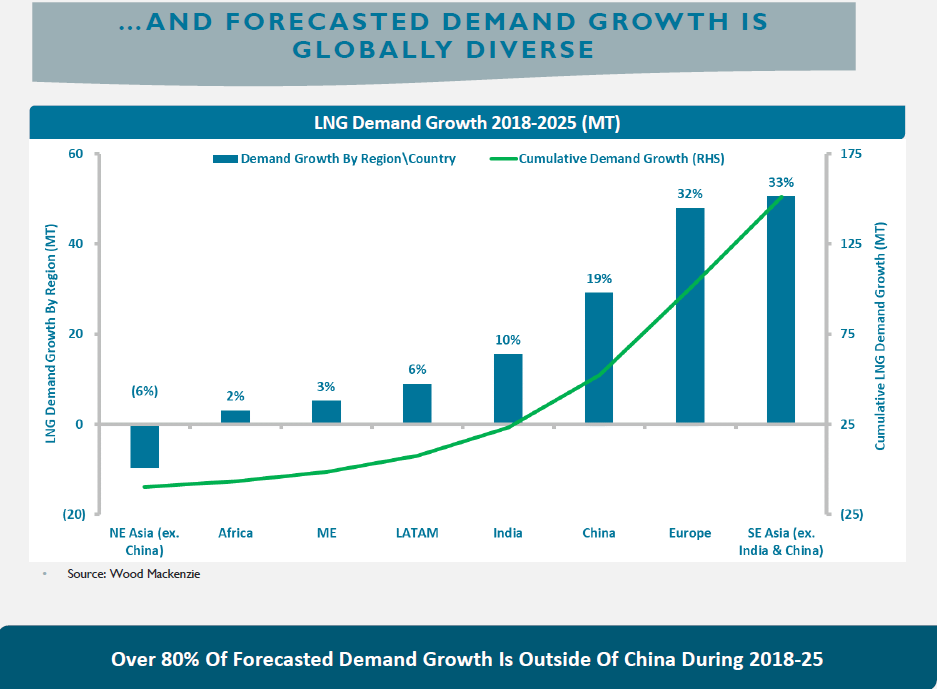

We hear a lot about the growth of China, and rightly so. But it’s interesting to note in Chart 1 that the forecast for demand is actually quite diverse globally. Over 80 percent of forecasted demand growth is from outside of China through 2025. You can see some of those regions in Chart 1—including Europe and Southeast Asia; quite big demand is there. It’s not all about China.

Chart 1

Looking at the supply side, the biggest growth has come recently from Australia and the U.S., and about 60 percent of that new capacity is [attributable to] the U.S. In fact, the U.S. production capacity just about doubles over the next year or so. The other top exporters are Malaysia, parts of Africa and Russia.

LNG prices are generally seasonal. They peak in the summer and winter months, and they’re softer in the shoulder months, such as in the fall. But there’s considerable regional variation even within countries. At the moment, a global economic slowdown and the U.S.–China Trade War are among the factors depressing LNG prices in the face of this new supply coming from the U.S., Australia and Russia. Currently, LNG prices are low, below $5 per MMBtu (million British thermal units). Those low prices may further delay the next wave of supply development projects.

Turning to Mexico, the rising U.S. production has enabled the U.S. to become a net exporter. At the same time, you have rising demand in Mexico, mainly to natural-gas-fired power plants, together with shrinking Mexican supply, which make Mexico an importer. U.S. LNG exports to the world will be increasing very significantly over the next several years, as I’ve said, but the exports to Mexico are and will continue to be mainly by pipeline, so the three LNG import terminals in Mexico—Costa Azul, Altamira and Manzanillo—are really shrinking in terms of import volume. The gas import story in Mexico is not going to be LNG; it’s going to be piped gas. This takes us back to the point Pedro (Niembro of Monarch Global Strategies) made about the infrastructure challenges of getting those pipes across the border to feed a potential plant in that location.

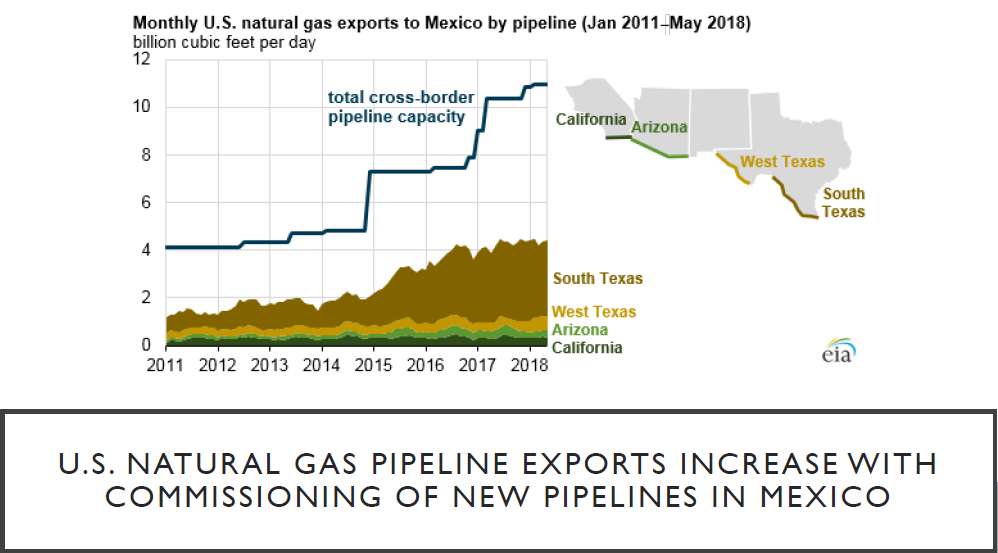

Chart 2 shows the increasing U.S. pipeline export capacity to Mexico. While gas exports by pipe started out mainly from the Eagle Ford (in south central Texas) and South Texas, producers now in the Permian Basin (in West Texas) have a huge incentive to export to Mexico. Pipeline capacity has been and is being built to satisfy Mexican demand by companies like Enbridge, Kinder Morgan, Energy Transfer and Howard Energy, among others. Kinder just started the Gulf Coast express pipeline, and U.S. production is at an all-time high partly for that reason. Also, natural gas exports to Mexico are at an all-time high and rising.

Chart 2

The capacity of the projects that are already in service and those that are in progress will exceed by far the actual exports to Mexico. So, that’s going to allow future supply growth to Mexico by pipe. But U.S. exports to Mexico will depend not only on cross-border pipelines but also on Mexican pipeline expansion and construction. However, there have been significant delays on the Mexican side that have resulted in low utilization of cross-border pipelines from West Texas.

This had been happening before (Mexican President) Andrés Manuel López Obrador and (U.S. President) Donald Trump. Unfortunately, the lack of pipeline infrastructure rendered Mexico unable to capitalize on the lower gas prices that we're seeing with gas in the U.S. So instead, the country was forced on numerous occasions to cut gas supplies, especially to industry more than residential.

That said about the problems in Mexico, some of the pipelines have been placed in service within the past year, such as the La Laguna–Aguascalientes. So, there is good news and progress on that front. But I want to make clear that the U.S. also has some challenging dynamics.

Liquefaction capacity for one thing has lagged the supply increases. The delays on those projects are not just all commercial or financial, but also regulatory. We have our own opposition among citizens’ groups to pipelines. Often, it’s environmentalists who are opposed to all forms of fossil fuels. In addition, landowners even in the state of Texas are opposed to these pipelines. Kinder Morgan encountered such opposition to its $2 billion Permian highway natural gas pipeline, trying to move gas from West Texas to the Gulf Coast.

In conclusion, I want to leave you with three takeaways. First of all, the global LNG supply demand outlook is robust, and that trend looks powerful and in place. Second, increasing U.S. natural gas production and declining Mexican production have resulted in exports of pipeline gas to Mexico. Finally, there have been logistic challenges on both sides of the border—in Mexico and in the U.S.— that have impeded progress. The good news is they are being resolved.