How Gen Z Texans use credit cards can shed light on their future financial health

Generation Z’s rising debt load has been widely reported, sparking concerns for the financial future of America’s youngest adult generation. Borrowers born between 1997 and 2012, ranging in age from 12 to 26, are more likely than other generations to max out their credit cards, according to the New York Fed, meaning they have used almost all of their available credit.[1]

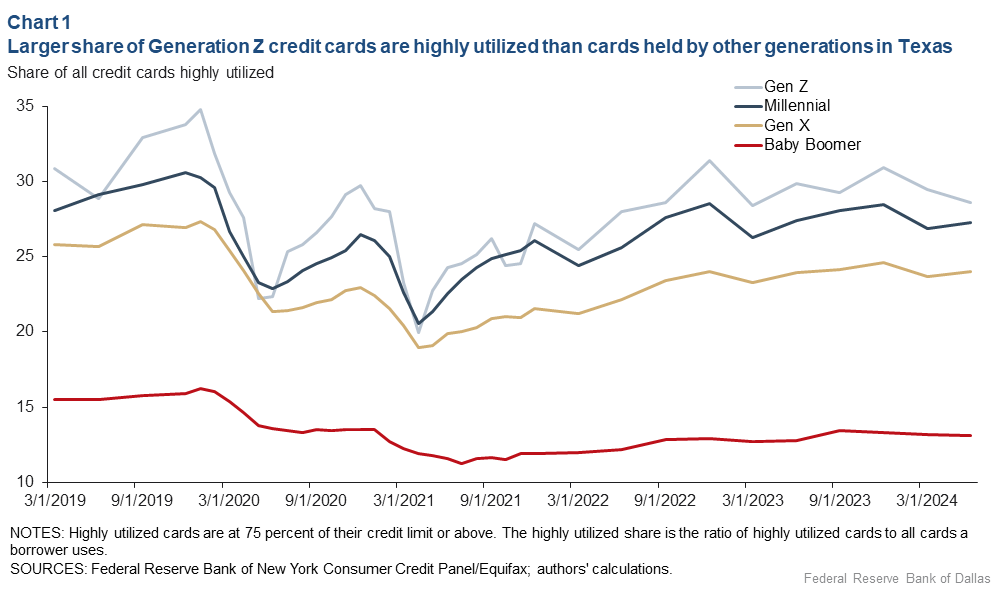

The data in the Lone Star state look very similar to national trends. Gen Z borrowers in Texas have a larger share of their cards highly utilized, at 75 percent of their credit limits or above, than other generations (Chart 1). Credit card utilization can be a strong predictor of delinquency and lower credit scores, and overextended credit cards have ramifications on one’s ability to save, build a credit history and prepare for the future.

However, younger people may have lower credit limits and be more likely to rely on debt than more financially established older generations. Therefore, comparing the credit activities of Gen Z to present day Baby Boomers, Gen Xers and Millennials fails to capture natural financial variations based on life stage.[2]

We compared Gen Z credit habits with those of prior generations when they were in their 20s, and we found some hopeful signs. The average Gen Z Texan uses credit significantly differently from the average Millennial or Gen X Texan when they were young. We followed these generational differences to the early 30s, as we consider how the differences in Gen Z’s credit behavior could influence their future credit health.

How much credit are Gen Z Texans utilizing? It depends on how you measure

Credit card ownership is more common among Gen Z Texans than the previous two generations.[3] Sixty percent of Gen Zers had at least one credit card in their early 20s compared with 54.5 percent of Millennials and 57 percent of Gen X consumers at those same ages.

This higher card ownership rate drives Gen Z’s higher utilization rates compared with the other generations. Taking each cohort regardless of cardholder status, Gen Z has a slightly higher average share of highly utilized credit cards than both Millennials and Gen X by age 25. When limiting the pool only to credit card holders, however, this reverses: Gen Z card holders have 28 percent of their cards highly utilized. For Millennials at that same age, 33 percent, on average, were highly utilized, and for Gen X, that share was 37 percent.

These generational differences invite a natural comparison. Credit utilization has a negative impact on credit scores in the short-term, and previous research indicated that credit behaviors in the short term can have long-term financial consequences. What might we glean from observing credit outcomes for Millennial and Gen X borrowers who behaved similarly in their early 20s to present day Gen Z borrowers?

We examined differences in credit card usage across generational lines using a 5 percent nationally representative anonymous random sample of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Equifax Consumer Credit Panel data for Texas residents. We compare a snapshot of usage by each generation at age 21–25, which we call “early 20s,” and again at age 30–35, called “early 30s.”

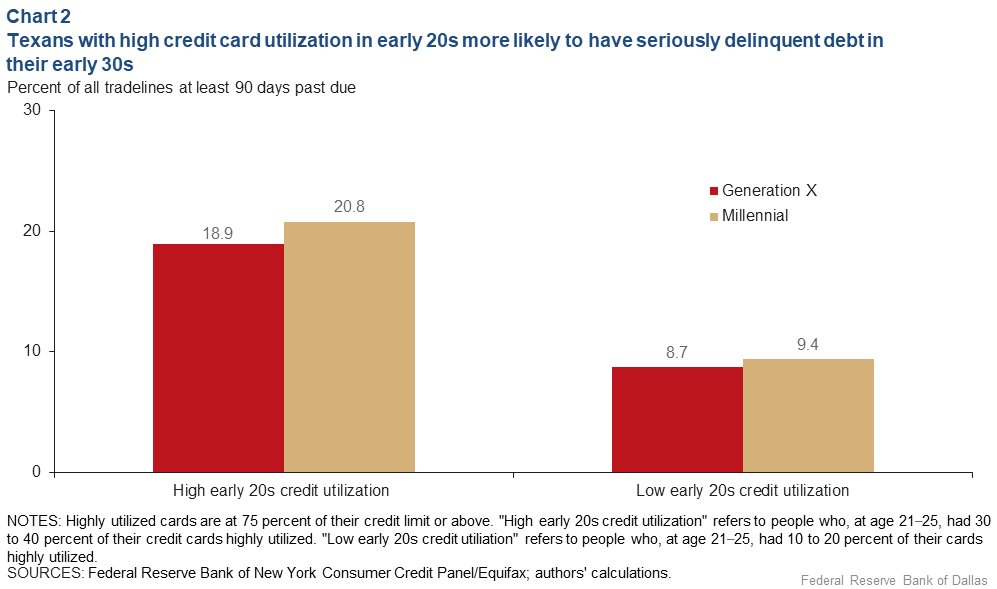

Credit card utilization in borrowers’ early 20s can help estimate future credit outcomes

We consider Texans with lower shares of their credit cards highly utilized (between 20 and 30 percent) at in their early 20s to be “low utilizers,” more similar to Gen Z, and Texans with higher shares of their credit cards highly utilized (greater than 30 percent but less than 40 percent) to be “high utilizers,” more similar to their own generational averages.[4] Following those cohorts, we find that Gen Xers and Millennials with utilization similar to Gen Z in their early 20s had lower rates of tradeline delinquency and higher average credit scores by the time they were in their 30s.

For example, Chart 2 shows that by the time Millennial Texans who had lower credit card utilization rates in their 20s were in their 30s, 9 percent of their lines of credit on average were seriously delinquent (at least 90 days past due). Compare that with Millennial Texans with higher utilization behaviors in their 20s; in the next decade of their lives, an average of 21 percent of their lines of credit were seriously delinquent. As indicated in Chart 2, Gen X shows similar patterns.

Unsurprisingly, these differences also show up in credit scores. Millennial Texans whose credit card utilization was lower than their generational averages in their early 20s had a 62-point higher credit score on average in their early 30s than their peers.

Do credit outcomes change based on income?

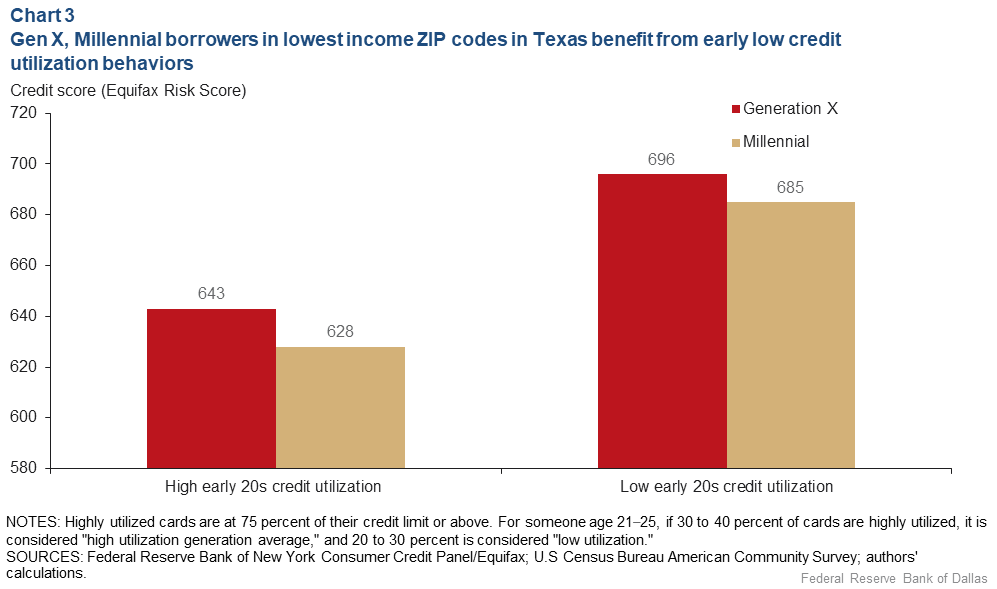

Our results also suggest this effect persists across early 20s income groups. Because individual income is not reported in the dataset, we use borrower location as a proxy and sort individuals into ZIP code income quartiles from the U.S. Census’ American Community Survey and the Decennial Census in years 2000 and 2010.

Looking only at a subsample of Generation X and Millennial borrowers who can be matched in their early 20s with income data, and controlling for income quartile based on the ZIP code in which they spent their early 20s, we find that statistically significant differences hold.[5]

For example, when we control for income quartiles, Gen X low-utilizers who lived in the lowest income ZIP codes in their early 20s experienced a 53-point credit score advantage in their 30s compared with their high-utilizing peers (696 compared with 643). Similar results, with a slightly stronger effect for the lowest income residents, are seen with Millennial Texans: low-utilizers in the lowest income quartile experienced a 57-point benefit in their early 30s compared with their high-utilizing peers (Chart 3).

Are the kids alright? A more complete picture is needed

These results suggest current rates of credit card utilization may be setting Gen Z borrowers in Texas on healthier paths than the previous two generational cohorts. Still, current credit card behavior is only one piece of a much larger picture of financial wellbeing. Importantly, the external economic environment will remain strongly predictive of credit behaviors. During the Great Recession, for instance, credit card utilization rates rose for most borrowers. This may have been especially relevant for those Millennials who reached their early 20s between 2007 and 2009.

Still, noting the distinct early credit behavior of this cohort compared with previous generations and tracing the impacts in older ages suggests hope for Gen Z borrowers, albeit subject to potential macroeconomic shifts. Moreover, drawing links between credit behavior in young adulthood and long-term credit health can help future generations of borrowers get strong starts to their financial lives.

Notes

- In this analysis we include only people born in 1997–2006 who have credit profiles.

- For generation cutoffs we use the following birth years: Baby Boomers, 1946–64; Generation X, 1965–80; Millennials, 1981–96; Generation Z, 1997–2012.

- Here and elsewhere in this article, "credit card" refers to a credit card issued by a financial institution.

- The measure of high credit utilization is highly bimodal: the plurality of cardholders in all generations does not have highly utilized cards, with the next greatest share having only highly utilized cards. To deal with this, we assigned utilization into four discrete ranges. Results are robust to specifications that hold constant those who have zero high utilization.

- Due to limited availability of U.S. Census American Community Survey (ACS) data for certain years, we limit our sample of credit borrowers to those who were 21–25 in years that align with data availability for five-year ACS and decennial Census estimates.

About the authors