Moving up, falling back or staying still: How income mobility in Texas differs by race, ethnicity

The previous article in this series explored income disparities among various racial and ethnic groups in Texas over time. Among the major findings were that Black and Hispanic Texans not only had lower earnings but had seen very little change in their relative earnings compared with white Texans from 2005 to 2019. However, there are other ways to evaluate economic outcomes that can contribute a different point of view to conversations about economic inequality.

In this article, we analyze how different demographic groups can climb the income ladder and move into higher-income groups. It may be that Texans who see little change in their relative earnings over time are in fact able to join higher-income groups easily. If so, the conversation on income inequality could be framed differently with this caveat in mind. Otherwise, if these demographic groups are similarly struggling to join higher-income groups, this could be indicative of a double whammy, where there are challenges improving not only within, but also across, income groups.

Examining mobility across income groups by race and ethnicity

We use the same data source as our previous article in the series: the Income Distributions and Dynamics in America dataset from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. This analysis uses 2014 as a baseline year and examines income mobility outcomes for demographic groups in Texas by comparing W-2 tax forms over five years (until 2019). We use four income quartiles to group them: those who are in the lowest earning quarter (“low income”), those in the second-lowest-earning quarter (“low-to-middle-income”), those in the second-highest-earning quartile (“middle-to-high income”) and those in the highest-earning quartile (“high income”). The data track how common it is for Texans to remain in their income group after five years or alternatively move up or down to other income quartiles. This data also track those who transition from any of these income groups to “missing” a W-2, which may indicate unemployment.[1]

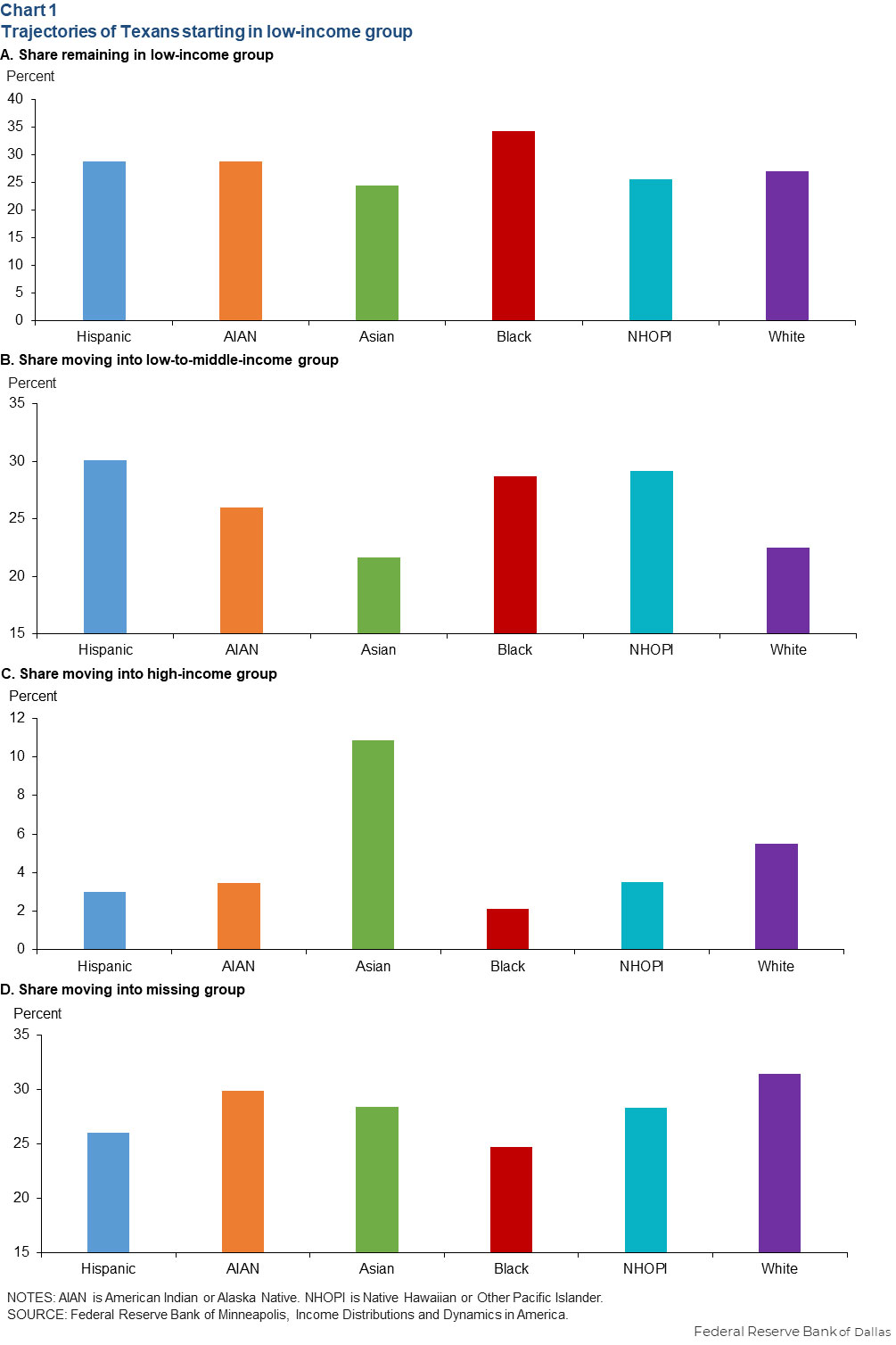

Chart 1A–D shows the share of low-income Texans by race and ethnicity who remained in the low-income group, moved into the low-to-middle-income or high-income group, or became missing from the data from 2014 to 2019.[2] For low-income Black Texans, the likeliest outcome is that they remain in the low-income quartile (over one-third of the time—Chart 1A). However, they also have the strongest attachment to employment and are the demographic group least likely to become missing from the data (Chart 1D). Nevertheless, the precariousness of Black Texans’ position in any income group is apparent from an analysis of those who start in the high-income quartile (not shown). Out of all racial and ethnic groups, Black Texans who begin in the high-income quartile are the least likely to remain there after five years (two-thirds of the time compared with 70 percent for Hispanic and white Texans and 80 percent for Asian Texans).

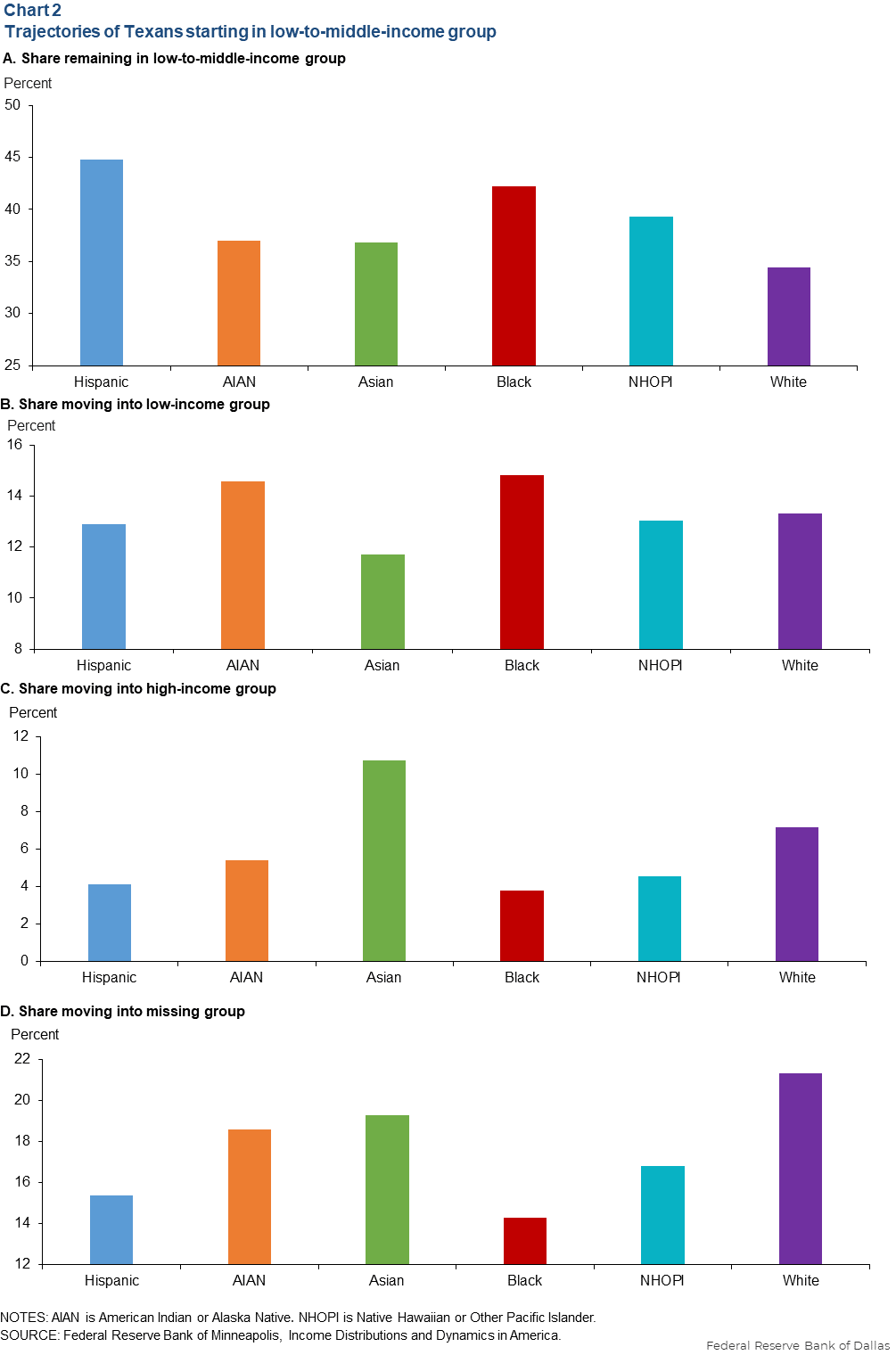

Hispanic Texans were the most likely to move from the low-income group to the low-to-middle-income group (three out of 10 succeeded in doing this) but were not particularly likely to advance further up the income ladder. As Chart 2A–D shows, Hispanic Texans in the low-to-middle-income group were likeliest to stay there, though advancement to the middle-to-high-income group was not uncommon. They were otherwise relatively stable within the other two income groups—not especially likely to move up or down.

Among other noteworthy trends, Asian Texans showed substantial upward mobility among income groups during this period. While the odds of moving from the lowest- to highest-income group were still low, 11 percent of Asian Texans were able to do so from 2014 to 2019. They were also the group least likely to remain in the low-income group. A similar pattern appears among Asian Texans starting in the low-to-middle-income group. While they were the unlikeliest to drop to the low-income group, they were again the likeliest to reach the high-income group.

The most striking trend among white Texans is not their relative mobility among income groups but rather their likelihood to transition to the “missing” group. About 31 percent of low-income white Texans are missing from the dataset after five years (again, indicating unemployment), the highest likelihood of all the racial and ethnic groups. White Texans in the low-to-middle-income group had roughly the same likelihood of moving up to the middle-to-high-income group as becoming “missing” from the dataset.[3]

Income mobility remains challenging for many groups

What do these patterns say about race, ethnicity and income in Texas during this time? While race and ethnicity do not predetermine one’s economic outcomes, there are important trends to consider at the aggregate level. As the previous installment in this series showed, racial and ethnic income disparities are well-documented over time, and with the notable exception of Asian Texans’ growth in relative earnings, these disparities have been unwavering. Black and Hispanic Texans in particular continue to earn less compared with their counterparts in most income quartiles.

This second installment also shows that income mobility is limited for many demographic groups. Black Texans see relatively little mobility across income groups, and Hispanic Texans do not generally experience much more. Asian Texans are again the exception to this overall trend, with relatively high likelihoods of advancing to higher-income groups. White Texans appear to have the most tenuous relationship to employment out of all the demographic groups rather than being especially likely to fall or climb to different income groups.

Not only are income disparities persistent over time and within income groups, but mobility from one income group to the next is relatively challenging. In fact, mobility is most limited for those with the widest income disparities, namely Black and Hispanic Texans.

This shows that economic advancement can be hard to achieve both within and across income groups. Policies intended to address income inequality in Texas may benefit from a multipronged approach, targeting both the disparities and the lack of mobility that we see.

Notes

- “Missing” simply means that the individual had a valid W-2 tax document in 2014 but did not have one for 2019. There are other potential explanations for an individual becoming “missing,” such as being deceased, but we assume the more common explanation is that workers have become unemployed.

- In this study, the Hispanic demographic group includes members of various racial groups. Other racial groups in this study consist of non-Hispanic individuals. For simplicity, we simply refer to these groups as white, Black, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN) and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI).

- The data only account for Texans who transitioned to and from the “missing” category and various income groups. Those who had no W-2 in either 2014 or 2019 would not be accounted for.

About the author