Rhymes with No Reason: A Second Look at Dollarization

I’m honored to be on a program with so many distinguished people. Officials like Governor Ortiz and Finance Minister Gil Díaz. When I was here last year, I assured them they needn’t worry about the United States slipping into recession. I need to find out what kind of Mexican wine goes well with crow.

And José Piñera, whom we hosted at the Dallas Fed several years ago to learn about Chile’s successful social security privatization. And academicians like Nobel laureate Robert Mundell, Allan Meltzer, Steve Hanke and others. I would mention my friend Roberto Salinas-León, but he’s too young. Probably young enough to fix the computer if anyone has a problem with his PowerPoint presentation.

Robert Mundell was already an icon in international economics when I was a student in the 1960s. The bibliography of my dissertation includes seven journal articles by Robert Mundell, eight if you count his article in the March 17, 1962, issue of The Economist. I assume it’s okay to count The Economist as an academic journal—isn’t it?

Actually, I have a small bone to pick with The Economist. On my way to work a couple of months ago, I heard a writer from The Economist being interviewed on the radio. He was saying in his fine British accent some of the same things about contemporary central banking issues that I had recently written in a poem. So when I got to work, I rang him up and read him my poem. He acknowledged the similarities, so I asked him to give my little poem to the letters editor of The Economist for possible publication. I thought I might get a journal article out of it. Long story short, the editor was unable to find any room for my little poem in his big magazine.

It’s not like it was my first poem, either. A while back, the Dallas Fed had a conference on dollarization. My job was to summarize the conclusions at the end of the conference, which I did quite nicely, I thought, with a limerick. Here’s my dollarization limerick:

There once was a hyperactive central banker,

Whose boat needed a stronger anchor.

The ocean was big,

The boat was small,

So he tied his anchor to a tanker.

Limericks have the advantage of being short. But serious poems don’t have to be long. My favorite serious poem is even shorter than a limerick:

Candy

Is dandy,

But liquor

Is quicker.

My favorite poet, Ogden Nash, wrote that. He also wrote other short ones:

God in His wisdom made the fly,

And then forgot to tell us why.

But an even shorter one may be more appropriate for an academic/think-tank conference like this one:

Purity

Is obscurity.

Since Cato is a libertarian think tank, I can’t resist sharing an exchange I found on a bathroom wall the other day, obviously put there by two libertarians. One guy had written: "Question authority." Under that, another guy had written: "Who the hell are you to tell me what to do?"

But I digress. See what you think of my little rejected poem.

With apologies to Ogden Nash—

Give Growth a Chance

From the backseat of a Grand Marquis,

My colleagues laughed at me

For having the temerity

To suggest the possibility

That Europe might have a new economy,

If only the ECB

Would set it free.

What I’d asked was so naïve,

They could hardly believe

That I could conceive

Of such a policy reprieve.

And they really looked askance

When I suggested giving growth a chance.

I understand that monetary policy

Is not the main villain of the European odyssey.

A good diagnosis

Of Euro-sclerosis

Would place more responsibility

On labor market inflexibility.

Laws against firing

Discourage hiring.

And too high a safety net

Is sure to snare and abet

Those dead set

On avoiding sweat.

When it comes to the ECB,

I understand it to be

Their single goal to protect the Euro nations

From inflations.

They said, "Rapid growth and low unemployment, Bob,

Is not the ECB’s job."

But I wonder if Europe really got a bargain in

Its inflation targeting.

I ask my questions anyway

To see what the experts would say.

But they’ve learned their lesson well:

To avoid central banker hell,

Dodge rhetorical questions

That lead in that direction.

The lesson is, don’t run an economy hot

Or you will surely not

Go to central banker heaven.

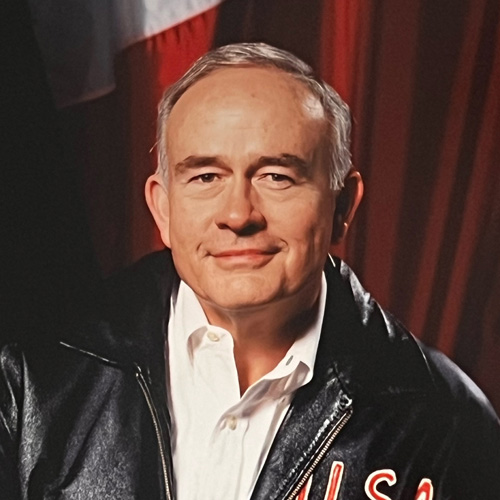

| — | Bob McTeer |

| July 2001 |

I understand that this conference is not about monetary policy in a new economy but about fixed and floating exchange rates. I’m not sure I could write a poem about that, but I did see a movie about them the other day.

Its title is O Brother, Where Art Thou? It stars George Clooney and two guys who look like North Georgia refugees from the movie Deliverance. The movie starts with George and his two colleagues on a chain gang in Mississippi, chained together at the ankles, busting rocks.

George needs to escape to find his wife before she marries another man—a man she says is bona fide. But he can’t escape alone because he’s chained to these two guys who aren’t likely to sympathize with his marital situation. So he makes up a story about buried treasure—gold buried in the ground, as I recall—and tells them he knows how to find it.

The three escape, running through the woods and down the dirt roads in lockstep because they are still chained together at the ankles. Like a three-man, three-legged race on the 4th of July—only they have four legs. They can go only as fast as the slowest man, and when one falls down, they all fall down. It’s not surprising that before long they are looking for a blacksmith. I’ll stop there so I won’t ruin the movie for you. By the way, the sound track is excellent. The theme song is "Man of Constant Sorrow."

You may think I’m beating around the bush here—not being as direct and explicit as I could be. I’ll admit it. I want to go to central banker heaven, too.

Look at it from my point of view: Does anyone really expect me to suggest publicly that Governor Ortiz and Finance Minister Gil Díaz should dollarize and turn policy over to the Federal Reserve? And does anyone expect me to offer up deep thoughts on optimum currency areas with Robert Mundell coming up this afternoon? Or deep thoughts on institutional reforms with Allan Meltzer on deck? I may be crazy, but I’m not dumb.

Actually, the theme of the conference, as stated in the program, probably already contains its conclusions. According to the program brochure:

The failure of pegged exchange rates, as witnessed by the numerous currency crises of the 1990s, has led to the recognition that in a world of mobile capital, a clear choice must be made between fixed and floating exchange rates. That choice has important political and economic consequences. Should Mexico dollarize and rely on the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy? Or can the Mexican central bank provide the discipline needed to maintain domestic price stability and let the peso float?

Implicit in that statement is a distinction between pegged exchange rates—which it says have failed, and fixed exchange rates—still a viable policy option. If so, I take "fixed" exchange rates to mean "really fixed." "Really fixed" used to mean currency boards, but I guess it now means dollarization, presumably because of Argentina’s recent difficulties.

No distinction was made between unilateral dollarization and dollarization in cooperation with U.S. authorities. I should make it clear that U.S. authorities, in this case, certainly does not include me. The Treasury is responsible for such matters, and I don’t even talk about them. Not in prose, anyway. But let me repeat my limerick:

There once was a hyperactive central banker,

Whose boat needed a stronger anchor.

The ocean was big,

The boat was small,

So he tied his anchor to a tanker.

Mexico’s leaders are perfectly capable of analyzing and choosing their options wisely. I don’t have a strong opinion either way. As a Texan might say, "I don’t have a dog in that fight." But I will say that it’s been a long time since Mexico has had a hyperactive central banker. That description certainly does not fit Governor Ortiz, nor Governor Mancera before him. In fact, I’ve teased Guillermo that he has only two kinds of monetary policy—tight and tighter. My words, not his.

I’ve defended elsewhere the Bank of Mexico’s failure to successfully defend the pegged peso during 1994. You’ll recall that 1994 was an election year in Mexico that opened with the Chiapas rebellion and featured the assassination of a presidential candidate and another political figure later in the year. Under the circumstances, it was reasonable to believe that the loss of foreign exchange reserves during the year would end when the election was over. That didn’t happen, but I think it was a reasonable expectation. One doesn’t want to be tighter than necessary, but it’s hard to tell how tight is necessary. Most of the post-devaluation criticism I put in the category of Monday morning quarterbacking.

It reminds me of Yogi Berra’s formula for success in the stock market. Or was it Will Rogers? Anyway, the rule is to buy the stock, and if it goes up, sell it. If it doesn’t go up, don’t buy it.

Of course, the sharp devaluation in December 1994 derailed Mexico’s successful multiyear march toward price stability, but sound monetary policy since then has successfully ratcheted inflation back down in the context—until recently—of strong growth.

In my opinion, the floating peso has served Mexico well. But the question is, Is well good enough? Good is sometimes bad if it precludes better. I’ve always believed in "If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it," but many new paradigmers are now telling managers, "If it ain’t broke, break it." I do agree that the choice is between floating and dollarizing and not between floating and repegging. I’m glad it’s not my decision to make.

Mexico not only has not had a hyperactive central banker in recent years, but its boat has grown larger and more stable. NAFTA has accelerated growth, and Mexico has surpassed Japan as the United States’ second-largest trading partner—second only to Canada. The past year notwithstanding, Mexico’s growing economic integration with the United States also makes the ocean less big for Mexico’s boat.

It is often said—and I agree—that obstacles to dollarizing are more political than economic, the biggest obstacle being the loss of pride in your own currency. José Cordeiro, an advocate of Mexican dollarization, has pointed out something that I had forgotten—in Mexico’s case, dollarizing wouldn’t be abandoning its currency but returning to it. When the United States was first creating its currency, it based the U.S. dollar on the Spanish/Mexican dollar, both in terms of silver content and in the symbol that we now call the dollar sign.

José quotes the U.S. Congress saying in 1792 that "the U.S. currency will be the dollar, equal to the strong Spanish silver peso." And he quotes Miguel Mancera’s recounting of it in 1982 as follows: "The circulation of the pesos was so prevalent in North America that in 1785, the U.S. congress commented that the Mexican peso, known in the Anglo Saxon countries by the name dollar, would be the ideal currency unit for the new nation."

According to José, the current dollar sign, or symbol, came from the Spanish royal family’s shield. The two vertical bars represented the Pillars of Hercules in Gibraltar and Morocco. They were crossed by an unfurled banner.

I’ll admit I didn’t know that. All I knew, or thought I knew, was that we got the word dollar from the Spanish dolar, which were sometimes called pieces of eight. The dollar coin was divided into eight sections, or bits.

Which brings us full circle. We end as we began:

Two bits, four bits, six bits, a dollar—

All for dollarizing, stand up and holler.

The views expressed are my own and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve System.