The Yahoo Economy

Glad to be here. Last time was in February 1994. At that time, the recovery from the Gulf War recession and the continuing expansion was nearly three years old. Now it's eight years and three months old. Inflation was down to about 3 percent then, a dramatic improvement. It's been 2 percent or less for a while now. The unemployment rate was around 6.5 percent. It's now 4.3 percent and has been below 5 percent for a couple of years. To summarize, most good things are up; most bad things are down. And some bad things—like the Asia crisis—were actually good for us in several respects for over a year, prior to the Russian default.

Earlier this year, the current expansion became the longest peacetime expansion in our history, surpassing the expansion of the ’80s. Early next year, the current expansion will become the longest, period—exceeding the wartime expansion of the ’60s. I see nothing to prevent us from getting from here to there.

Everything is not perfect with the economy. Our personal saving rate is too low. Our trade deficit is too large, which means we are relying too much on foreign saving and capital. Marginal tax rates are too high. Government is too big. Improvements can be made, but these problems are not a clear and present danger to the continuation of the expansion. On the other hand, the last recession was triggered by the Gulf War, which came out of nowhere.

Until about three and a half years ago, our economic growth rate was not spectacular, but it was persistent. How long it takes to drive to California depends in part on how fast you drive, but it may depend more on how many pit stops you make. For the country as a whole, we've had only eight months of recession since November 1982. Eight months out of 208—about 3.5 percent of the time. From the 1850s to the 1950s the economy was in recession 40 percent of the time—three steps forward and two steps back. No longer. "Slow and steady" has replaced forward and back, stop and go. Progress compounds with few interruptions. To summarize—and remember, you heard it here first—the economy has been doing well because it hasn't been making many pit stops.

This economy has been breaking a lot of the old rules recently, or what people thought were rules. The main broken rule is the idea that you can have low unemployment or you can have low inflation, but you can't have both at the same time. The 1970s taught us that you could have high unemployment and high inflation at the same time—stagflation—but not a low combination. But during the ’90s, and especially in the last few years, we have had strong growth with declining inflation.

For a while the reason was a mystery. A mysterious X Factor. I understand that before Pluto was discovered the behavior of the other planets suggested that something was there—an X Factor. We assumed that the X Factor in the economy was productivity growth, driven by the revolution in technology. That's all that made sense of a lot of things. But the problem was that it's hard to measure productivity in a service economy, and productivity showed up everywhere but in the statistics.

Something happened in the early ’70s that slowed productivity growth substantially—the inflection point was 1973. From the early ’70s to the mid-’90s productivity growth—that is, output per hour worked—grew only about 1 percent per year. If output per hour is increasing at only 1 percent or slightly more, and if the number of hours worked increases at about the same rate, then sustainable real growth is only a bit over 2 percent a year.

But in the second half of the ’90s, real growth has averaged about 4 percent a year, due about equally to a pickup in employment growth and in productivity. Last year, 1998, more hours worked increased about 2 percent and output per hour increased about 2.2 percent, for a growth in output of 4.2 percent. In the fourth quarter of 1998 and the first quarter of 1999, productivity growth averaged 4 percent—a doubling of the doubling, if for only a while.

Can we sustain a 4 percent growth rate this year and beyond? I have a lot of faith in our high-tech revolution—the Yahoo Economy. The Digital Economy. Or the Internet Economy. In the ’60s the word to graduates was "plastics." In the ’90s the word is "silicon," as in chips. Sustaining 2 percent productivity growth, or maybe more, for the next few years seems possible to me—even likely.

But the 4 percent real growth rate of the past three and a half years has also depended on employment expanding faster than the growth in the labor force. That's why the unemployment rate has declined so much. There has also been an increase in the labor force participation rate during this period. And welfare reform has helped as well. Since 1994, 1.4 million adult workers have moved from the welfare rolls into the labor force.

But the pool of available, capable, but not employed workers to draw on to sustain recent growth is diminishing rapidly. On May 20, the Wall Street Journal ran a short op-ed piece by me where I suggested two reforms to help augment the labor force: remove the steep penalty for Social Security recipients who wish to continue working part time or full time, and relax immigration quotas on highly educated, high-skilled foreign workers needed by our high-tech industries.

Top students from all over the world attend graduate schools in U.S. universities, studying math, science, electrical engineering, etc.—all areas where our high-tech industries have many, many jobs to fill. Yet we send most of them home because of immigration quotas. I got a letter from a student at the University of Texas who had married a German exchange student also in graduate school there. He was going to have to return to Germany against his wishes and take her with him, even though the German government had no objection to his staying and working here.

Filling open and begging high-tech jobs with skilled foreigners, who might later become Americans, does not destroy American jobs. It creates them, as new projects are able to go forward. Removing the high-tech bottlenecks will create all sorts of collateral jobs. The alternative is for our high-tech firms to relocate abroad to find the workers they need.

Before I stop for questions, let me mention monetary policy and its role in our second-wind, higher gear, digital, Yahoo, new paradigm, new era economy.

Monetary policy wasn't too good in the 1970s. It let inflation get out of hand, which created an economic environment that encouraged price increases as an alternative to reducing costs and getting more efficient and productive. That has now changed. In today's more stable monetary environment, along with globalization, price increases are less of an option and getting lean and efficient is essential to survival.

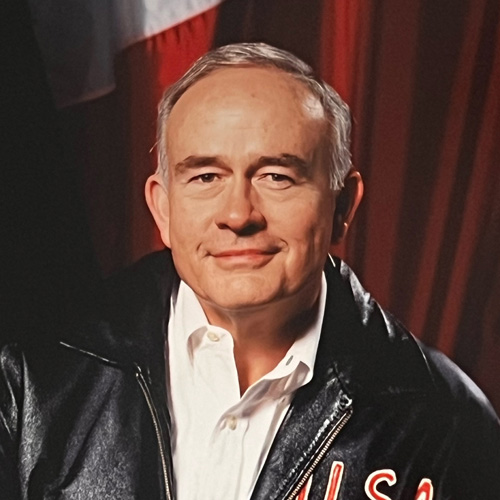

Beginning with Paul Volcker in 1979 and continuing with Alan Greenspan in 1987 and Bob McTeer in 1991, the Volcker-Greenspan-McTeer Fed (😄 just kidding) has moved the economy most of the way to price stability—with very few pit stops along the way.

Of course, we had a little bit of help. We were helped by the end of the 50-year war: WWII plus the Cold War, the fall of the Iron Curtain, the lowering of the Bamboo Curtain and the curtain of protectionism in Latin America. In other words, by globalization. And by freer trade within the globe. We were also helped by deregulation of many industries, by tax cuts in the ’80s and by removal of the budget deficit more recently.

And we were helped by the microchip and all the technologies it spawned. Just as electricity augmented the muscle power of the Industrial Revolution at the end of the last century, the microchip augments the brainpower of the Information Revolution at the end of this century. And, remember, the Internet is only a few years old for most of us. Sooner or later, virtually every industry is likely to be Delled by the Internet—as in Michael Dell.

In summary, monetary policy has been disinflationary, but so have peace, free trade, more competition, restructuring, downsizing, lower taxes, the microchip and the Internet.

What about salesmen? Poor Willy Loman, and he didn't even have the Internet to contend with. The Internet is going to be especially hard on salesmen. But, fortunately, salesmanship will be needed more than ever.

The views expressed are my own and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve System.