How global oil sanctions lowered Russian oil export prices

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 prompted widespread voluntary restrictions on imports of Russian crude oil, which were replaced by a formal oil embargo in December 2022 and a cap on the price of Russian crude oil sold to countries not participating in the embargo, which took full effect in early 2023.

Why a price cap was added to the oil embargo

The price cap policy replaced an earlier, more comprehensive European Union (EU) sanctions policy prohibiting seaborne oil imports from Russia and banning the provision of financial services to companies transporting Russian crude. That policy was to take effect by year-end 2022.

Many observers at the time feared that, especially were the U.K. to follow the EU’s lead, these sanctions would cripple Russian oil exports by making it impossible to operate tankers carrying Russian oil to countries not participating in the sanctions, thereby causing a surge in the global price of oil and, hence, a global recession.

The introduction of a $60-per-barrel price cap effectively allowed the EU to relax the ban on using Western financial services in shipping Russian oil cargoes to other countries, while retaining the oil embargo.

According to the U.S. Treasury, this price cap was designed to achieve two goals: First, to keep global energy markets well supplied and avoid a price shock that would hurt the global economy and, second, to limit the Kremlin’s ability to fund its war in Ukraine.

A recent Dallas Fed discussion paper concludes that the first of these objectives was achieved by linking the price cap to the availability of maritime services for the transport of Russian oil to Asia. However, the price cap alone did little to lower Russian oil export prices. Its effect on Russian resources available to wage war was limited primarily to the funds the price cap caused Russia to spend on acquiring additional oil tankers.

In other words, an embargo that allowed Russia to freely use Western maritime services without a price cap would have had essentially the same effect on the free on board (FOB) price received by Russia as the sanctions ultimately adopted, which involved an embargo coupled with a price cap that allows Russia restricted access to Western maritime services. This conclusion is supported by the evolution of Russian oil export prices.

Effect of the sanctions on Russian oil prices

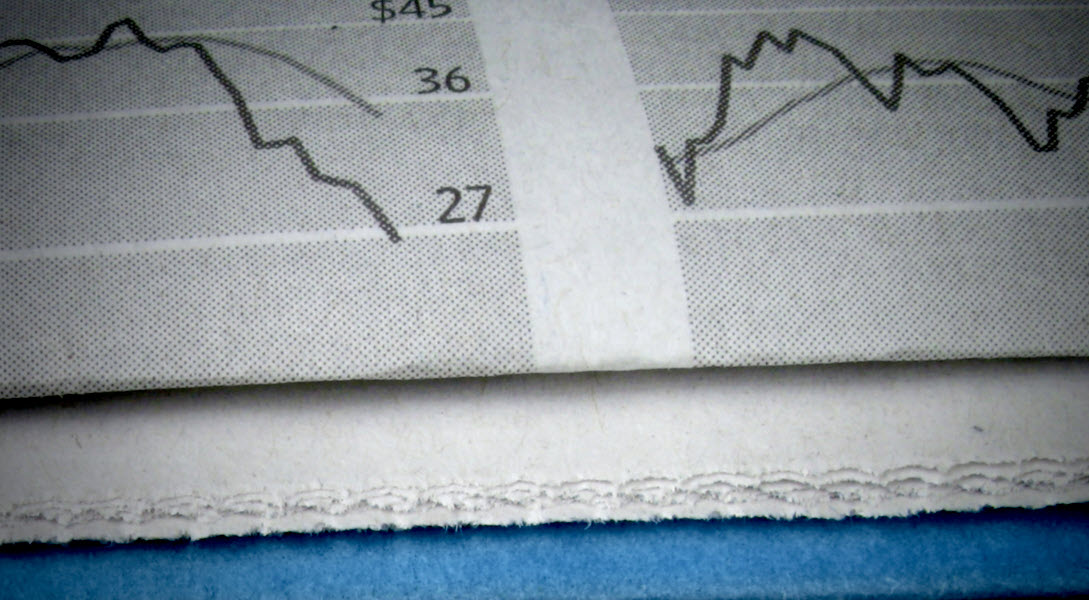

The Russian FOB price in 2023 was systematically lower than the Brent price, the reference price for crude oil in Western Europe. The price of Russian ESPO (Eastern Siberia Pacific Ocean) oil in the Far East has been consistently above the price cap (Chart 1).

The price of Russian Urals crude shipped from the Baltic Sea and Black Sea fell far below the $60 price cap in early 2023, before rising well above the price cap later in 2023 (Chart 2). This evidence tells us that the Russian export price would have been largely the same if the price cap had simply been discontinued in early 2023, while maintaining the embargo.

For example, when the Russian export price in the first half of 2023 fell below the price cap, importers of Russian oil had the same access to Western maritime services as they would have had if all restrictions on maritime services had been removed, so the price cap did not matter.

Likewise, to the extent that Russian export prices exceeded the price cap in the second half of 2023, the price cap must have been of limited relevance for Russian export prices. This is consistent with the view that Russia was able to circumvent the price cap by utilizing oil tankers that do not rely on Western insurance or oil tankers that operate in violation of the price cap.

Bloomberg estimates that more than 70 percent of Russian seaborne cargoes in the first nine months of 2023 were loaded onto tankers not subject to the rules imposed under the price cap. Some of these vessels were Russian-owned, but many were not. Even granting that some shipments were sold at the price cap, the availability of a large tanker fleet beyond the control of the Group of Seven industrialized nations explains why the average observed Russian export price exceeded the price cap in the second half of 2023.

If the price cap did little to reduce Russian oil prices, why did the Russian Urals export price drop so far below the price cap in the first half of 2023, and why was this decline reversed later in 2023?

Role of the oil embargo

When formal sanctions had taken effect in March 2023, Russian exports of Urals oil traded at an added discount of $32 per barrel relative to Brent crude. Comparisons of import and export prices of Russian crude oil suggest that roughly half of this discount arose from the oil embargo, which segmented the global oil market and forced Russia to redirect its oil exports to India and China. As Russian oil traveled over greater distances, the cost of transportation increased, which lowered the price Russia was able to charge for its oil.

More formal analysis based on a calibrated model of the global oil market suggests that the remainder of the price discount can be explained by a modest increase in the market power of India, the only remaining large importer of Russian Urals oil. The same economic determinants explain the price discount for Russian ESPO crude.

Chart 3 summarizes the effect of the oil embargo and market segmentation on Russian export prices and the global oil price, taking account of fluctuations in oil demand and supply unrelated to the sanctions.

The erosion of the Russian FOB discount in the second half of 2023 is likely explained by several changes in market conditions. For example, Russian seaborne crude oil exports declined 20 percent between March 2023 and November 2023, the most recent date for which accurate data on bilateral oil trade flows exist. As less oil was being exported by sea, the demand for oil tankers fell and so did the cost of transporting crude and hence the Russian price discount.

In addition, Russia has also become more adept at bypassing embargo restrictions by disguising the origin of its oil exports, which reduces the market power India and China previously enjoyed, as does the recent increase in Turkey’s oil imports from Russia.

Price cap did not work as intended

The decline in Russian oil export revenue since January 2022 was achieved by reducing the Russian export price rather than the volume of Russian oil exports. Estimates suggest that roughly half of the steeper Russian price discount in May 2023 arose from Russia having to redirect its oil exports to more distant destinations. The remainder of the change in the Russian price discount can be explained by a modest increase in Indian and Chinese market power due to the segmentation of the global oil market.

In contrast, while the price cap played an important political role in ensuring continued access to Western maritime services for Russian exports to Asia, it had only a negligible effect on the Russian price discount in 2023, once the sanctions were imposed.

While it is conceivable that tightening the enforcement of the price cap could substantially improve its effectiveness, so far the improved enforcement of the price cap starting in October 2023 has had only a modest effect on the FOB price discount for Russian Urals oil relative to Brent. The discount was $13 per barrel in September 2023. By February 2024, it had increased only by a few dollars to $17, with the Urals price remaining above the price cap of $60.

About the authors