Hang your hat in Texas: State remains a leader in firm relocations

When companies are on the move, many head to Texas. Among the attributes driving this migration are relatively low taxes and light regulation, as well as high growth and a relatively low cost of living.

Recently released data through 2019 show Texas remains a juggernaut, a leader for business relocations. And while figures covering the subsequent pandemic era and beyond are incomplete, anecdotal evidence suggests Texas remains a go-to spot.

The National Establishment Time Series (NETS) documents the number of businesses moving between states, including to and from Texas, the employment impacts of this business migration and the distribution of those movers among urban, suburban and rural areas of the state.[1]

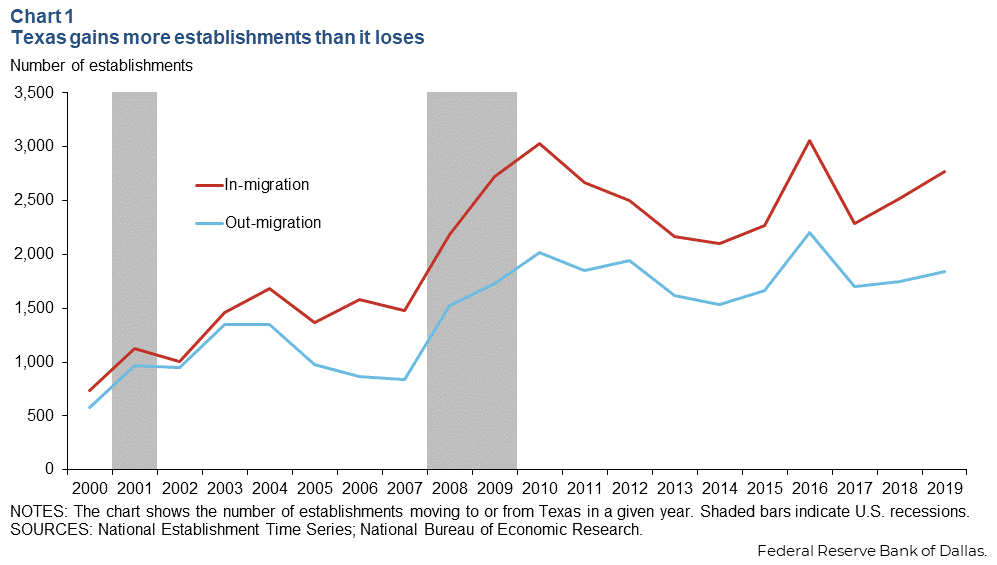

From 2000 to 2019, the number of establishments moving into Texas annually exceeded the number of establishments leaving the state (Chart 1).

More recently, more than 25,000 establishments relocated to Texas from other states from 2010–19, bringing more than 281,000 jobs. At the same time, just over 18,000 establishments left the state, costing about 179,000 jobs. The result: a net migration of 7,232 firms and an addition of nearly 103,000 jobs.

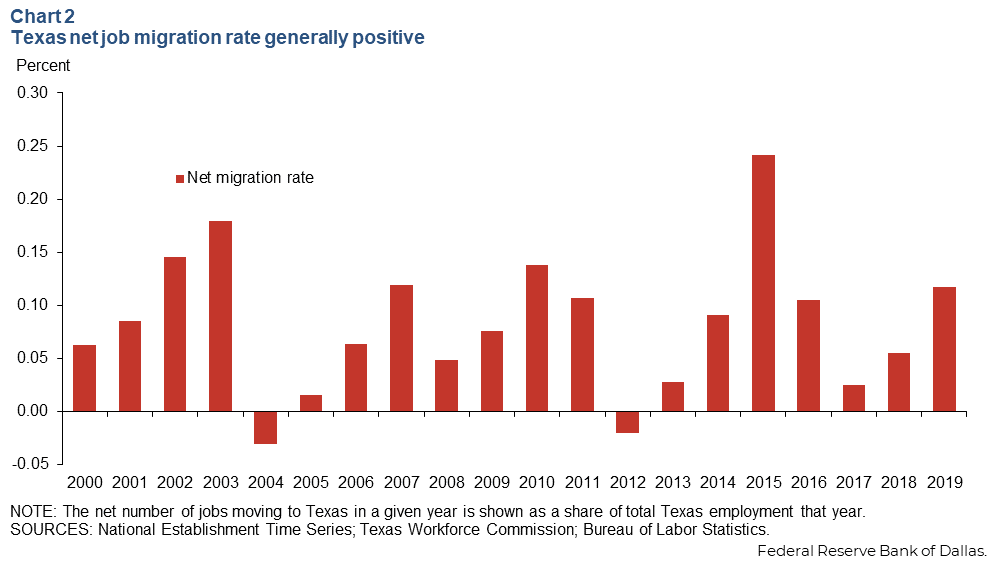

Job gains due to firm in-migration averaged around 0.24 percent of Texas’ total employment, exceeding the average out-migration rate of 0.15 percent. The net job migration rate, the number of jobs moving in minus the number moving out, as a share of total employment, was positive in all but one year during the past decade (Chart 2).

Texas remains a top destination

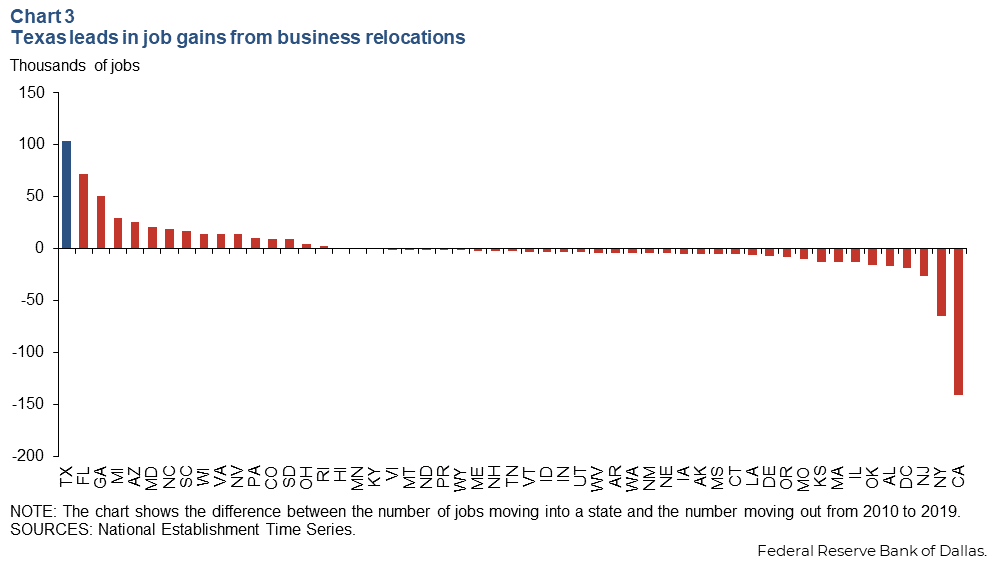

These numbers were enough to make Texas a top destination nationally between 2010 and 2019. Texas ranked second among states in the net number of businesses acquired and was No. 1 in net jobs gained from out-of-state business relocations during the period.

Florida led the net business count, followed by Texas, South Carolina, North Carolina and Arizona. In net jobs gained, Texas was followed by Florida, Georgia, Michigan and Arizona (Chart 3).

The story changes slightly when examining net job migration attributable to business relocations as a share of overall employment. Texas remains high but sixth nationally, trailing South Dakota, Georgia, Nevada, Arizona and Florida. California ranks sixth from the bottom, with the District of Columbia exporting the most jobs as a share of overall employment, followed by Delaware, Alaska, Kansas, Oklahoma and Vermont.

California remains a top job exporter

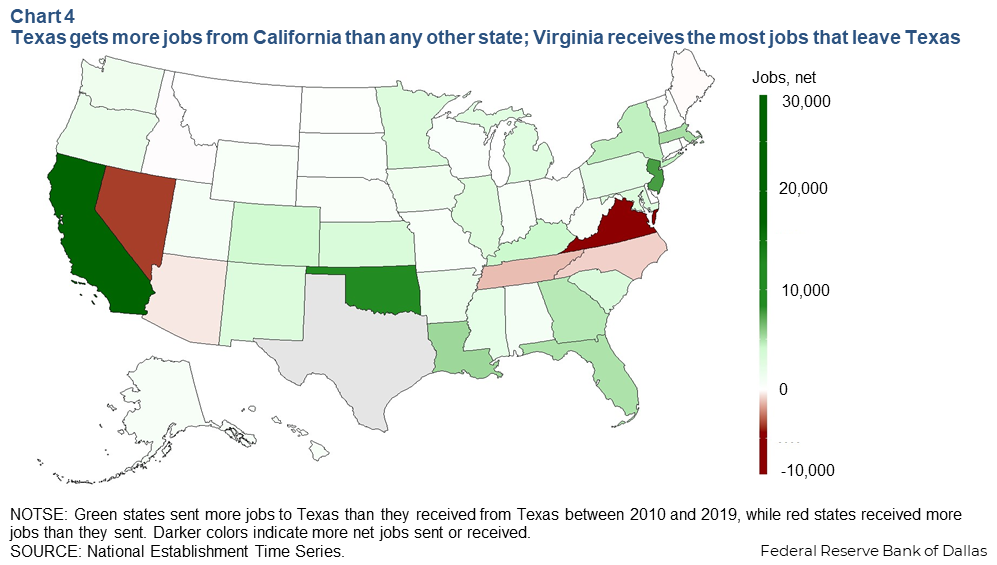

In terms of total job outflows associated with business relocations, California again emerged as the largest net exporter of jobs nationally, and Texas remained a favored destination for businesses departing California. Between 2010 and 2019, California was the source of over 44,400 jobs moving to Texas, about 16 percent of all jobs relocating to the state. Meanwhile, Texas sent just over 14,700 jobs to California for a net migration of 29,700 jobs to Texas.

Others leading net job migration to Texas were Oklahoma, New Jersey and Louisiana (Chart 4). The relatively high job migration numbers from Oklahoma and Louisiana suggest that, in addition to differences in economic conditions and business climates, proximity is an important factor.

Virginia was the top recipient of jobs from Texas during this period, gaining more than 8,600 positions on net. Overall, 41 states were net job exporters to Texas, highlighting the state’s drawing power.

Firms mainly moving to Dallas, Houston

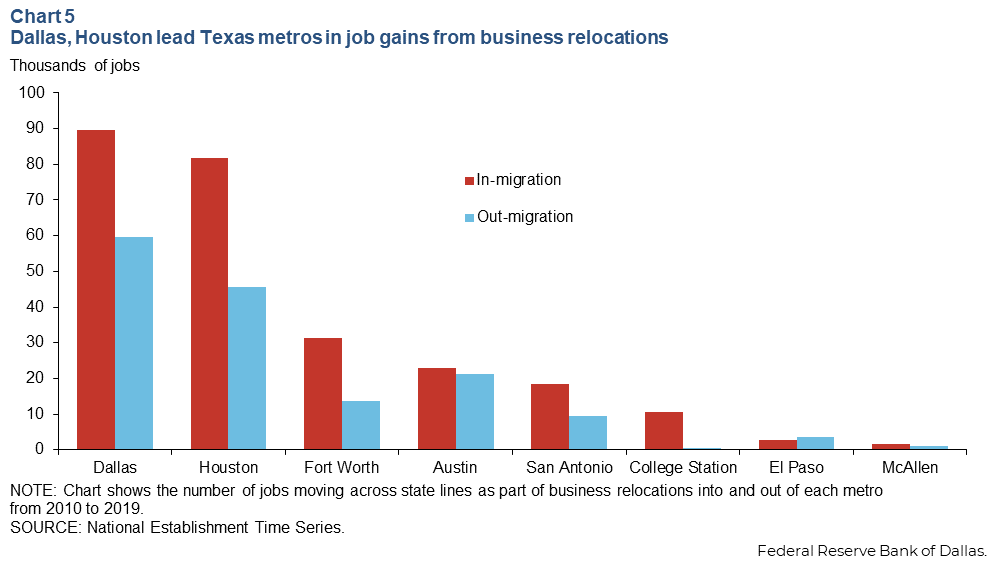

Businesses relocating to Texas mostly went to large metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), and Dallas and Houston were the favored destinations. The two metros accounted for three-fifths of all jobs moving from other states (Chart 5).

The choice of large MSAs is driven not only by the growth and relative size of these geographic areas but also by population density, availability of an educated workforce, diversity of industries, infrastructure and access to good schools.

During the decade of the 2010s, Dallas, Houston, Fort Worth and Austin ranked as the top four MSAs in Texas in terms of the net migration rate of jobs from interstate business relocation.

Most job gains in professional services, manufacturing

Among the major employment sectors, professional and business services accounted for just less than 30 percent of the jobs associated with firm in-migration during 2010–19, followed by manufacturing (17.7 percent) and trade, transportation and utilities (17.1 percent). These sectors also made up the bulk of jobs moving from Texas during the same period (Table 1). Almost all major sectors experienced positive net job migration from business relocation, with only information losing jobs. Professional and business services and manufacturing were responsible for close to 50 percent of moves.

| Table 1: Migration of estabishments and employment by sector | |||||

| In-migration | Out-migration | ||||

| Supersector | Establishments | Employment | Establishments | Employment | |

| Professional and business services | 12,604 | 83,831 | 9,138 | 52,340 | |

| Manufacturing | 1,638 | 49,758 | 1,084 | 30,316 | |

| Trade, transportation and utilities | 3,114 | 48,314 | 2,332 | 30,486 | |

| Leisure and hospitality | 1,270 | 24,299 | 831 | 9,915 | |

| Construction | 1,507 | 16,128 | 944 | 8,330 | |

| Educational and health services | 1,754 | 14,497 | 1,380 | 11,958 | |

| Finance | 1,382 | 13,915 | 979 | 8,763 | |

| Mining, oil and gas | 260 | 13,327 | 136 | 3,574 | |

| Information | 560 | 10,199 | 391 | 18,083 | |

| Other services | 870 | 5,024 | 632 | 3,209 | |

| Agriculture | 389 | 1,197 | 261 | 615 | |

| Total movement | 24,809 | 274,268 | 17,215 | 173,765 | |

| NOTES: Table shows movements from 2010-19. Supersectors shown represent a subset of total Texas mover population, so columns do not sum to entries in the "Total movement" row. SOURCE: National Establishment Time Series. | |||||

Small firms are more mobile; big firms bring more jobs

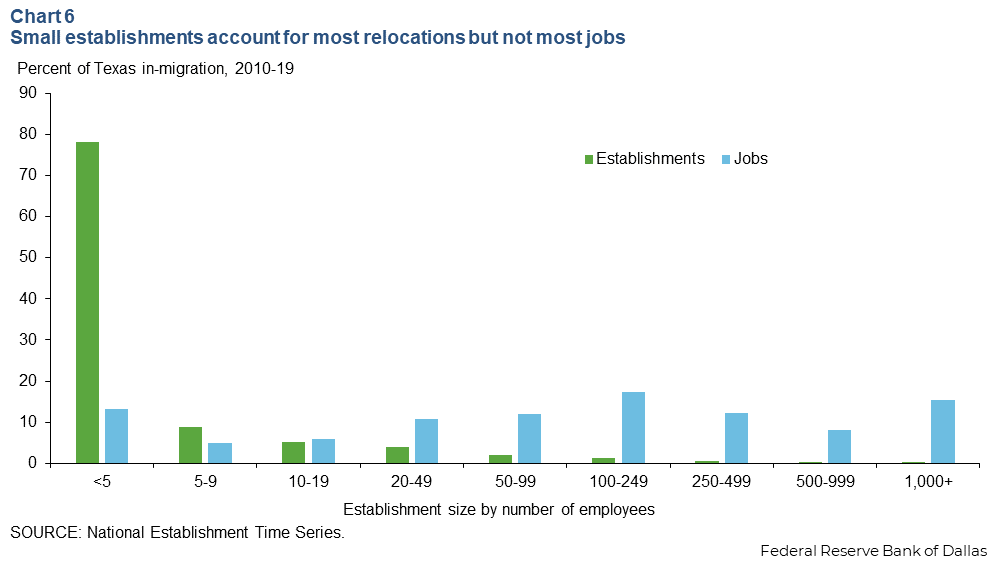

Not surprisingly, small businesses tend to be more mobile than large firms. On average, 90 percent of businesses moving into or out of Texas were stand-alone, single-establishment entities. They accounted for about 50 percent of net job migration to Texas. Establishments with fewer than five workers constituted about 80 percent of all businesses relocating to Texas but accounted for less than 14 percent of all jobs moving in (Chart 6).

The number of multi-establishment firms, those with multiple locations, relocating their headquarters to Texas represented about 50 percent of employment moves. Large establishments with 1,000 or more workers account for very few moves but about 15 percent of jobs coming to Texas.

Overall, firms with fewer than 500 workers are responsible for about three-quarters of jobs coming to Texas. The average establishment size of all in-migrating businesses is about 11 workers, with a median of two workers, meaning many are hardly bigger than proprietorships.

Small establishments moving to Texas generally exhibit stronger growth than large ones if they succeed. Small businesses tend to be younger and contribute more to net job creation over time than their large counterparts.

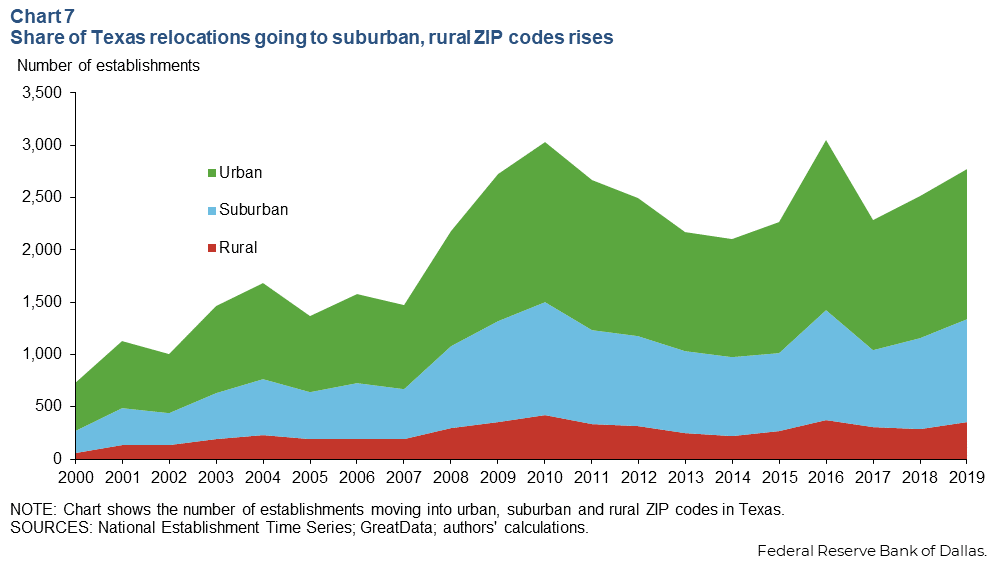

Urban areas were the destination for 53 percent of business relocations to Texas during the 2010–19 period. Suburban areas captured 36 percent, while rural areas attracted around 12 percent of relocating businesses (Chart 7).

The share of businesses that locate in suburban and rural areas has been rising over time. Businesses choosing rural destinations tend to be in agriculture, mining, recreation and manufacturing.

Gauging the impact of new arrivals

While firm relocations often grab headlines, the number of businesses moving to or from Texas is actually a small share of overall establishments in the state. Accordingly, any particular move has only a small impact on the state’s overall economic activity. Businesses relocating to Texas accounted for only 0.12 percent of the nearly 2.3 million establishments in the state in 2019, and businesses leaving totaled 0.08 percent, for a net in-migration rate of slightly more than 0.04 percent of Texas’ establishments.

Similarly, although jobs from business relocations remain an important focus of state and local policymakers, these jobs are just a minor component of the overall churn in the labor market. More significant contributors to job growth in Texas include job creation from newly created firms and expansion at continuing ones, countered by job destruction from business closures and job losses in contracting businesses.

The Texas economy created about 1.4 million jobs and destroyed 1.2 million jobs per year between 2010 and 2019, for a net job creation per year of about 216,000 jobs, the Census Bureau's Business Dynamic Statistics data indicate.

Thus, the 28,000 jobs gained annually from businesses coming to Texas from 2010 to 2019 accounted for just less than 2 percent of all net job creation in the average year. In other words, more than 98 percent of new positions came from either newly created businesses or growth among expanding Texas firms.

Analogously, the 18,000 jobs lost per year due to businesses moving out of Texas represented just 1.5 percent of all jobs destroyed. Therefore, the net migration of 10,000 jobs per year from other states to Texas represents about 5 percent of annual net job creation in the state.

Relocation has costs, benefits

With new enterprises, local residents benefit on average from new business investment, greater employment opportunities and increased property values that lead to net gains in economic welfare. New firms can also have significant positive spillover effects for existing entities and, through agglomeration economies, increase overall productivity and wages.

However, some residents may benefit more than others. Renters, for example, may struggle to get wage increases that keep pace with rising rents, while landlords benefit from higher property values. Homeowners will reap the gains from higher house prices when they sell, but, in the meantime, they are stuck with higher property taxes. Commuters contend with more road congestion until more roads can be built.

While the majority of business moves to Texas involve small entities with few employees, interstate relocations of large firms that bring many workers can come with larger benefits—but sometimes also at a cost to taxpayers.

Cities and states compete with each other for relocation wins, often with the aid of incentive packages, that may include cash grants, tax incentives and targeted expenditures on infrastructure and public services. Notably, research has found that economic fundamentals are far more important than incentive packages in location and expansion decisions. A survey of such studies found that for at least 75 percent of incentivized firms, the firm would have made a similar location, expansion or retention decision absent the incentive.

Texas offers range of incentive programs

Texas offered about two dozen programs to attract businesses from other states from 2010 to 2019. Key among them has been the Texas Enterprise Fund, one of the largest deal-closing funds in the nation. The fund provides cash grants to mostly large companies that choose Texas over another state and create at least 75 jobs in urban areas (25 jobs in rural areas) with mean wages above the county average.

The enterprise fund participated in 201 projects from its inception in 2004 through 2022 at a cost of $830 million. Notable among them, Samsung won $27 million to build a semiconductor plant in Taylor, 50 miles northeast of Austin, and create 1,800 jobs. Samsung has said the facility, announced in 2021, is scheduled to open at the end of this year, though reports have indicated mass production won’t begin until 2025.

Another widely used program provided tax incentives under Chapter 313 of the Texas Tax Code. It was allowed to expire in December 2022 and has been replaced with a scaled down version, Chapter 403.

Chapter 313 allowed school districts to provide property tax incentives by capping a new firm’s appraised property value for 10 years. In return, a business committed to create at least 25 jobs in a nonrural school district (10 in a rural district). The state makes up the foregone school tax revenue. A total of 598 awards worth $12.2 billion were made as of June 2022.

Still other property tax abatements offered by cities and counties under Chapter 312 of the Texas Tax Code don’t involve state funding but are used to attract new industries and retain existing ones.

Good fundamentals drive location decisions

A variety of factors make Texas a favored destination for businesses intending to relocate. Some relate simply to the state’s traditional advantages. These include a favorable business climate in the form of relatively low taxes and less regulation, growing population, central location, large size and multiple large cities, accessibility to ports and proximity to Mexico, diverse industrial structure and abundant energy resources.

Other characteristics also work to Texas’ advantage: an ample supply of educated workers relative to many other states, a lower cost of living than other large states and less union activity.

A lower tax burden is a central part of Texas’ appeal to business. The Tax Foundation ranked Texas 13th among states on business tax climate in 2023. The state has no individual income tax and low unemployment insurance taxes. However, sales and property taxes are relatively more burdensome, and companies often pay a margin tax (formerly the franchise tax).

Tax incentives are likely unavoidable when competing for interstate relocations, but evidence suggests that subsidies go to relatively few firms and at best play a small role in affecting location choices. Texas’ traditional growth advantages appear to predominate when it comes to business relocations with the added benefit that they also support firms already in the state.

Note

-

The National Establishment Time Series database, constructed by Walls & Associates and Dun & Bradstreet, tracks the characteristics and movement of about 60 million U.S. establishments from 1990 through 2020. Data showing establishment movements are complete through 2019. Available establishment characteristics include location, employment, sales, industry, headquarters and first and last years of operation. Establishment characteristics are updated annually. When an establishment relocates, NETS provides a move event record that changes its street address and ZIP code. A move event record includes location details pre- and post-move.

The NETS database covered 2.3 million Texas establishments, accounting for 15.2 million employees, in 2019. By comparison, the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages covered about 700,000 Texas establishments, with 10.7 million employees, in 2019.

About the authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.